by Ray Zone

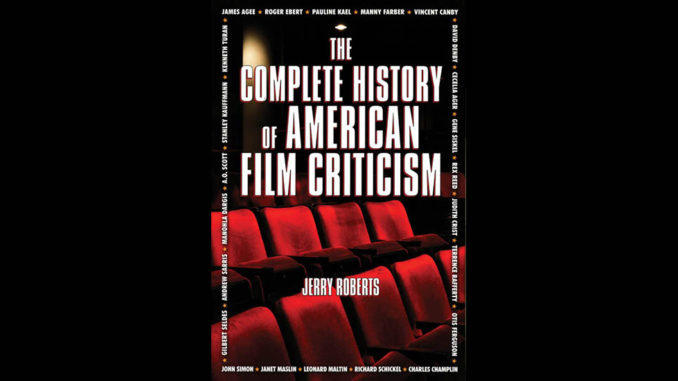

The Complete History of American Film Criticism

by Jerry Roberts

Santa Monica Press

480 pps., hardbound, $27.95

ISBN: 978-1-59580-049-7

I once tried to join a very exclusive club. Having written numerous articles about motion pictures and a couple of books of film history, I figured I might have a shot at it. Even eliciting the requirements for entry, however, proved to be a challenge. After great efforts at achieving elucidation, I was informed that I had to write regularly for a daily or weekly newspaper reviewing films on a regular basis. I had to have done this for a considerable period of time and then be voted in by the membership who, even if I met these rigorous requirements, may ultimately just not like my face. Admission to this exclusive club, I found, was a highly quixotic affair and, ultimately, I threw up my hands and considered the grave question of whether, like Groucho Marx, I would even want to join a club that would admit me as a member. This professional “club” was the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, first formed in 1975.

So, having made my confession, I must admit to reading Jerry Roberts’ The Complete History of American Film Criticism with great fascination. It is an encyclopedic effort to chronicle the rise and flowering of film criticism in the 20th century and its evolving––and diminishing––influence in the 21st. It is “intended as a narrative history to explain who was who in film criticism,” Roberts explains, and “when they wrote, what publications they wrote for, and why they were important.” As well, it “was written as a general, accessible, fact-packed compilation concerning the nature and scope of––and changes and controversies in––film criticism in the United States.”

Though Roberts’ definitive history stands alone in its scope and sweep, it can be well placed on the bookshelf beside American Film Criticism: From the Beginnings to Citizen Kane, the 1972 compilation of “Reviews of Significant Films at the Time They First Appeared,” edited by Stanley Kauffmann with Bruce Henstell, and Nine American Film Critics: A Study of Theory and Practice by Edward Murray from 1975. Beside the countless collections of film reviews published as books by the numerous film critics discussed in Roberts’ volume, I would be remiss if I also did not mention Raymond Haberski’s fine history from 2001, It’s Only a Movie: Films and Critics in American Culture.

Within the chronological framework of his narrative history, Roberts embeds mini-biographies of the important and influential critics in the cultural and social context of their times. The passions and controversies which led to the formation of such organizations as the National Board of Review of Motion Pictures (1909), the New York Film Critics Circle (1935) and the Hollywood Foreign Press Association (1943) are given a balanced discussion inside this narrative framework. It also covers film critics like Frank S. Nugent, Peter Bogdanovich, Roger Ebert, Paul Schrader and Rod Lurie, all of whom crossed the journalistic “fence” of objectivity to become filmmakers.

One of the most important film critics who gave new importance and literacy to the job with a deceptively “light-hearted yet perceptive analysis of the movie medium,” to quote historian Myron Lounsbury, was Otis Ferguson. Roberts notes that Ferguson, beginning in 1934, “maintained his forum at The New Republic by embracing the medium and coaching it, sternly rebuking it when he thought the movies were overly coy, unduly petulant or trotting out the same song and dance.” Ferguson subsequently became a role model to many future film critics, including James Agee and Manny Farber in particular, who brought the craft to new, if idiosyncratically cantankerous, heights of literacy.

Film critics could be a decidedly prickly lot. It went with the territory and, to some extent, was a measure of their independence and freedom from studio ballyhoo and publicity. Farber, writing in a variety of publications, was a shining example of sinuous intelligence and independent spirit. “Manny Farber is one of the very few movie critics who have mattered in this country,” wrote film critic Richard Schickel. Dwight MacDonald said that Farber was “as perverse and original a film critic as exists or can be imagined.” Farber, notes Roberts, “found meaning in items that the critical establishment found cheap, tawdry and unworthy.”

Farber’s 1950 essay “Ugly Spotting” in The Nation, for example, “shows that at least one American critic was as savvy as the French in discovering, even if he didn’t name it, film noir,” writes Roberts. “These super-tabloid, geek-like films [The Set-Up, Act of Violence, Asphalt Jungle, No Way Out] are revolutionary attempts at turning life inside out to find the specks of horrible oddity that make puzzling, faintly marred kaleidoscopes of a street, face or gesture,” wrote Farber.

Many tales of critical blasts are amusingly told by Roberts. These include Judith Crist’s characterization of Delmer Dave’s family film Spencer’s Mountain (1963) as a “deplorable” product of the “trite aspirations of vulgarians,” as well as Pauline Kael’s description of David Lean’s Ryan’s Daughter (1970) as “gush made respectable by millions of dollars tastefully wasted.”

I have to admit that I take exception to Roberts’ characterization of Susan Sontag as a “dabbler” in film criticism. Her 1965 essay “The Imagination of Disaster” from Commentary magazine is perhaps the most insightful analysis of the 1950s science-fiction films ever written. But, then again, Sontag didn’t have to live her life on what LA Weekly film critic Michael Dare bluntly called the “crap patrol” of film criticism sitting day-in and day-out through films of every stripe.

I guess that’s what also excludes me from this select minority––numbering only about 100––who are on daily cinematic patrol. I also take comfort from Roberts’ citation of the fact that Manny Farber was “rejected by the Communist Party in his twenties, by the US Army during World War II, and by the New York Film Critics Circle after one meeting––and after the group had asked him to join.”