by Paul Hirsch, ACE

My fascination with the movies started in Paris when I was a child. My father was a painter, and my mother was a dancer. We lived in Paris for four years, and part of my connection to “the States” was going to American movies. The French have a real love/hate complex about America, and though they claim feelings of cultural superiority, Paris is in love with Hollywood.

(When Jean-Luc Godard made his film Masculin-Feminin, he included a card that read: “This film could also have been entitled ‘The Children of Marx & Coca-Cola.’”) Luckily for me, they insisted on showing pictures VO (original version), ie, with subtitles (in French of course). So we American ex-pat kids loved going to the movies. One of my favorites was King Solomon’s Mines. I also recall seeing Scaramouche, Ivanhoe, The Greatest Show On Earth, The Crimson Pirate with Burt Lancaster and Road to Bali with Bob Hope and Bing Crosby.

I remember going to An American In Paris numerous times. When I was a kid, if I found a movie I liked, I would see it over and over again. I wonder if this capacity for repeated viewings was an early indicator of my future career. In any event, this film was a natural for me, since it told the story of a painter (like my Dad) who falls in love with a dancer (like my Mom), and of course, I was the American in Paris!

So it is altogether fitting that I saw the movie that propelled me into my career while in Paris. A senior in college, I was already enrolled in Columbia Architecture School in the fall, but I needed a few more credits to qualify for my degree. By luck and good timing, I was able to do this by taking two French classes in Paris. Class was over each day by noon, and I often would spend my time seeing old Hollywood pictures that played in art houses on the Left Bank. The auteur theory and the Cahiers Du Cinema in full tilt, there were festivals devoted to the work of a single director––like Raoul Walsh or Howard Hawks. It was the first time I paid any attention to who the director of an American movie was.

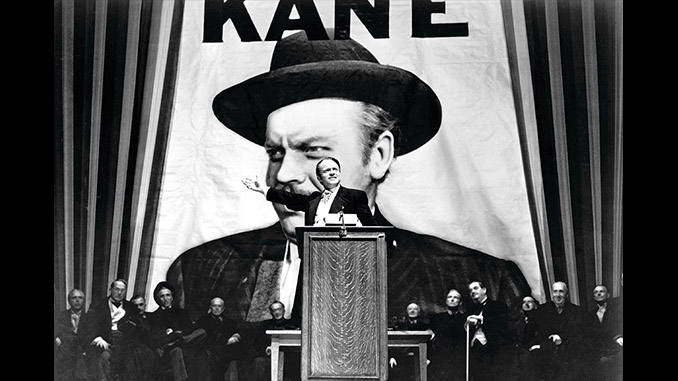

The breakfast scene, with dazzling economy, told the story of Kane’s deteriorating marriage as it demonstrated time passing.

That summer, the Cinematheque at the Palais de Chaillot was having an Orson Welles Festival. I had seen him once or twice, as an actor on TV. He would make himself up onstage while reciting a scene from Othello, or as Falstaff, but I had never seen any of his pictures. So I went on a Monday night to see Citizen Kane, which I had vaguely heard of. To my surprise, although the print had no subtitles, film enthusiasts filled the theatre nevertheless, even though they didn’t speak English.

With no foreknowledge about the film, I was thrilled to the core. The joy of discovery is hugely underrated, and I have never understood why people want to know beforehand the story of a movie they are going to see. I was thunderstruck. From the opening sequence, with Kane breathing, “Rosebud” on his deathbed, to the final revelation of what that word meant, I was in its thrall. The brilliant manipulations of time and space, and the fascinating character exploration of this tragic “great man” excited me to no end about the potential of film as a medium.

In particular, I was fascinated by the breakfast scene, which, with dazzling economy, told the story of Kane’s deteriorating marriage as it demonstrated time passing. The framing device of the newsreel researcher, the various points of view of the recollections of Kane’s associates, the fascinating visual compositions, the evocative lighting, the magnificent sets, that music, the camera moves––like the one that went through a rooftop sign and down through a skylight––and especially that final shot: flying over all the art he had collected in his lifetime right to the shattering realization of what Rosebud meant, told through visual means. All were part of the magic for me.

Citizen Kane affected me profoundly. I returned every night that week, and saw The Magnificent Ambersons, The Lady from Shanghai and Touch of Evil! On Friday, the Master himself was appearing with Macbeth, and you couldn’t get near the place. Those pictures, all in a week, excited an ambition in me to participate somehow in making movies.

When I went back home, and enrolled in Architecture School, I knew deep down that it was not for me. After a couple of months, I dropped out and was able to land a shipping room job at an industrial film house in New York City. But it was in Paris that my career really began.

Paul Hirsch is an Academy Award-winning picture editor and a member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and the American Cinema Editors (ACE).