by Kevin Lewis

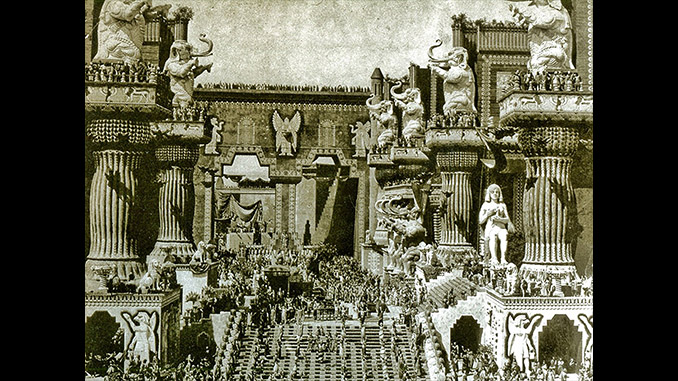

Filmmaker D. W. Griffith was both the most revered and controversial figure in the nascent American film industry 90 years ago when Intolerance premiered in Riverside, California on August 5, 1916. In just eight years, the failed playwright and actor had transformed silent film narrative and editing in over 100 short films and early features, culminating in the Civil War and Reconstruction epic The Birth of a Nation (1915).

With the millions earned by that film, Griffith produced Intolerance: A Sun Play of the Ages, which mystified audiences but inspired filmmakers worldwide. Whereas Nation examined the collapse of feudal Southern patriarchy, Intolerance explored labor clashes in the United States and religious conflicts throughout the ages. Together, the films represent two sides of the political coin, but reflect the dilemma of Southerner Griffith confronting a pluralistic United States.

Intolerance towers above Nation, a narrow-minded (and extremely racist) narrative, because of its Olympian view of collective history. Though it was a commercial flop in America––leading Griffith to cut the modern story into The Mother and the Law (1919) and the Babylonian story into The Fall of Babylon (1919)––Intolerance was especially appreciated by Vladimir Ilyich Lenin in the new Soviet Union as a model of both editing and narrative for propaganda purposes.

Griffith became the artistic father of such Soviet filmmakers as Sergei Eisenstein and V. I. Pudovkin, who wrote the pioneering texts on motion picture editing: the former’s Film Form: Essays in Film Theory and The Film Sense and the latter’s Film Technique and Film Acting. The principles of montage and rapid cross-cutting developed by Eisenstein, mostly notably in the Odessa Steps sequence of The Battleship Potemkin (1925), can be traced back to the fall of Babylon and the last minute rescue of the death row boy in Intolerance.

Intolerance posited the sophisticated idea that the philanthropy of the Robber Baron era was misguided. In the modern story, a society woman hides her disgust for the workers in her brother’s mill by forming a self-righteous moral reform society at the workers’ expense. Her brother reduces the low wages of his workers by ten percent to pay for her charity. A strike ensues, workers are killed and the newly unemployed drift to a city where they become involved in crime.

Intolerance was especially appreciated by Vladimir Ilyich Lenin in the new Soviet Union as a model of both editing and narrative for propaganda purposes.

Three tragic historical stories of the razing of Babylon, the crucifixion of Jesus, and the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre of the Huguenots by Catherine de Medici, are intercut with the modern story and support the thesis of religious and social hypocrisy. The recurring image of the woman who rocks the cradle (Lillian Gish) acts as a leitmotif connecting all of the stories and illustrating the theme of the title card: “Out of the cradle endlessly rocking…today as yesterday, endlessly rocking, ever bringing the same human passions, the same joys and sorrows.” With this image, John Howard Lawson wrote in Film: The Creative Process (1964), Griffith “suggested the hidden ties that link each individual to the movement of history… Instead of exploring the meaning of history, we are told that it is always the same, a static opposition of good and evil.”

Lewis Jacobs described in The Rise of the American Film (1939) the relentless editing by Griffith and his longtime editors, the brother-and-sister team of James and Rose Smith. “By an overlapping of movement from one shot onto the next, a double edge is given to the images and strong tension is created. Each shot, moreover, is cut to the minimum; it gives only the essential point. Facts build upon one another in the audience’s mind until, in the very last shot, all the facts are resolved and summarized through the introduction of another type of shot, longer than any of its predecessors and significantly different in character.

“Not only the cutting and treatment of the sequences, but the deliberate documentary quality of the shots themselves, are remarkable,” Jacobs continues. “Huge close-ups of faces, hands and objects are used imaginatively and eloquently to comment upon, interpret and deepen the import of the scene, so that dependence upon pantomime is minimized.”

By juxtaposing the four ancient and modern eras, Griffith replicated the synapses of the brain that can connect nonlinear information. Intolerance is not just ahead of its time; it represents all time, all human experience.