by Michael Kunkes

If you think that unwrapping the mysteries of transcoding file-based camera footage provides its challenges, you will find the post-production workflow on Avatar either very scary, or a completely visionary model of things to come. Learning and creating as needs arose, picture editors James Cameron, A.C.E.; John Refoua, A.C.E.; and Stephen Rivkin, A.C.E.; as well as assistant editor Jason Gaudio and producer Jon Landau, have created a unique process that was centered completely on director Cameron’s final goal of bringing forth the most photoreal look in CG and performance-capture history––complete with its own lexicography. The following is a somewhat bare-bones and linear description of that process.

Beginning in April 2007, Cameron directed actors in full motion capture suits on the Volume, the performance-capture stage at Giant Studios in Playa Vista, California, six times the size of any previous capture stage, with over 200 motion-capture cameras recording data. The motion capture data was streamed to Autodesk Motionbuilder software for character setup. Concurrently with this initial batch of performance capture, as many as a dozen reference cameras were shooting low-resolution footage of the actors to document their performances. This footage was streamed live into the Avid on stage. Four of these reference cameras were captured at a time, creating “quad splits” in the Avid, to save storage. There would usually be two quads representing the various reference footages for each scene.

During this phase of the production, Cameron focused on the actor’s performances and not on shot creation. The actors also wore a head rig, which contained a camera and a close mic directly in front of their faces. This rig would record dialogue and capture their facial performance. Because the actors are actually wearing a camera in addition to the tradition- al motion-capture facial markers, the captured information could later be interpreted with an unprecedented frame-by- frame level of detail.

Next, in an initial editing stage, and perhaps the most complicated, Cameron, Rivkin and Refoua edited a “performance cut” from the reference cameras to judge performances. This was akin to a first cut on any live action movie with the exception that the camera angles were for reference only, and showed the actors in their performance-capture suits. During this stage, various takes would be used to create a spine for the scene. Layers of reference cameras were combined in a picture-in-picture mosaic style to show crowd and stunt elements, which would eventually be used to complete the scene.

Once selects were made on performance, the editors would create camera “loads” to divide the scene into shootable sections. These camera loads would be used to create the eventual shots for the movie and were basically re-playable files containing the selected performance takes that were captured earlier.

Camera loads, depending on complexity, would include motion that was “combo’d” (different actors’ performance takes are combined into one load), “stitched” (joining parts of different takes to make one continuous take), or created through FPR (Facial Performance Replacement, a performance-capture equivalent of ADR, created by Cameron, in which faces are taken from an alternate take or even another body to replace an existing character part). The camera loads are then turned over to the “Lab,” the in-house visual effects house––built for the film––that created many of the movie’s virtual environments, which were blended with additional motion refinements from Giant.

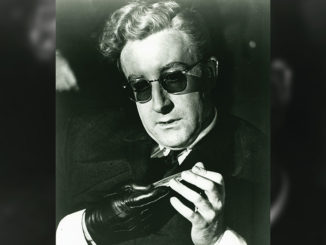

Bottom: Final image after addition of high-resolution visual effects and facial mapping by WETA Digital.

Images © 20th Century Fox Film Corporation

Then, in perhaps the most critical process of Avatar as far as editing is concerned, Cameron revisited the Volume, this time with a virtual camera that is actually a hand-held monitor with controllers linked to a motion-builder box. Using the built-up and pre-selected camera loads provided by editorial, Cameron used this virtual camera, through which he viewed the characters and environments to effectively create the action on the moon Pandora on the fly, as it were, utilizing the focal length and zooms on the camera to create limitlessly scaled motion and tracking shots.

On the stage, in almost real time, the output from the virtual camera was streamed to the Avids, and the editors cut the now-much-more-movie-like scenes right on the stage, fine-tuning later in their cutting rooms. Having already selected the performance that would be the basis of each camera load, Cameron could focus on shot creation, and explore the best way to tell the story. At this point, there would be dailies for each scene representing the previous performance selects and the new shots created by Cameron on the performance-capture stage.

At the conclusion of this process, called the Template, the Lab updated shots from Cameron’s notes and cleaned up the motion. Also, Wheels, another in-house process set up by Cameron, fine-tunes the 3-D, after which the shots are sent to the WETA effects house in New Zealand for final processing, where the captured facial data is mapped and fully rendered onto the body performances, using the company’s own software. Adhering to the template guide, WETA recreated everything it received in high definition, with realistic lighting and effects.

After months of preparation by sound, music and picture editorial, the final images were cut in and sent to the Howard Hawks Stage at Fox for the final mix, which was being done by re-record- ing mixers Andy Nelson, Gary Summers and Chris Boyes––the latter also serving as the supervising sound editor and sound designer on the picture.