by Mel Lambert • Stills by Jaimie Trueblood/Columbia Pictures

It is a late Friday afternoon in November and the post-production crew is carefully refining the soundtrack for a scene from Reel 6 of director Morten Tyldum’s Passengers. Reacting to notes from picture editor Maryann Brandon, ACE, re-recording mixer Kevin O’Connell is handling music and dialogue elements while Will Files is wrangling sound effects and serving as supervising sound editor. Also present on the Kim Novak Stage at Sony Pictures Studios in Culver City, is ADR supervisor R.J. Kizer, who coordinated the intricate robot and computer voices used in the sci-fi drama written by Jon Spaihts.

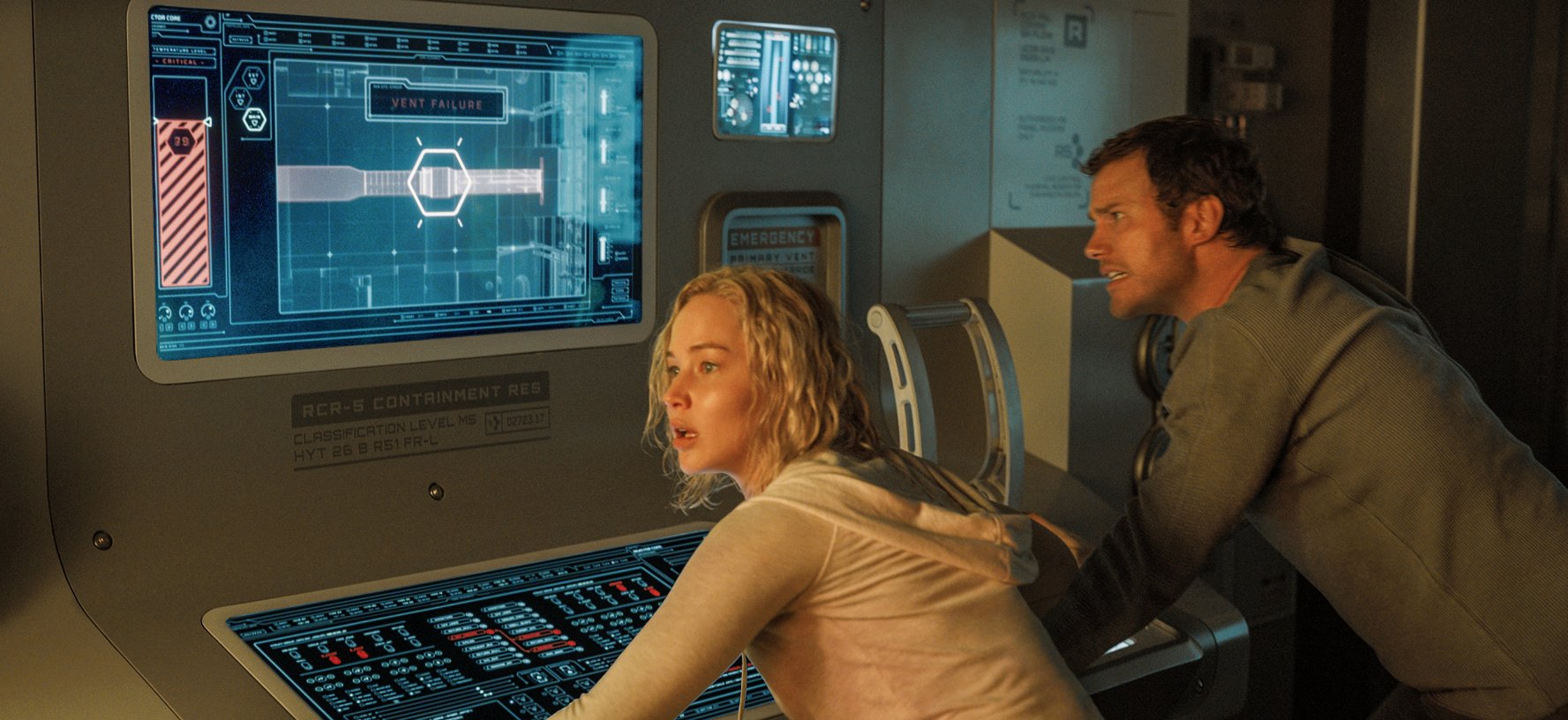

Starring Jennifer Lawrence, Chris Pratt, Michael Sheen and Laurence Fishburne, and scheduled to open in the US on December 21 through Columbia Pictures, Passengers chronicles the fortunes of two passengers aboard a futuristic spaceship who are being transported them to a new life on a distant planet. The trip takes a deadly turn when their hibernation pods mysteriously wake them 90 years before the Starship Avalon reaches its destination. As the duo tries to unravel the mystery behind the system failure, they are threatened by the ship’s imminent collapse and gradually discover the truth behind their awakening.

As Files halts playback, we hear the reverb and ambiences die away from the Avid Pro Tools sessions that hold the soundtrack’s Dolby Atmos immersive mix. “Those ambiences and reverb spaces for the ship interiors and outer space views complement the film’s highly developed space ship visuals,” Files explains. He adjusts assignable controls on the Avid S6 control surface with Joystick Module and a PEC/DIR panel, located temporarily atop the room’s Harrison MPC4D digital console, which on this project is only handling playback monitoring. O’Connell is using a pair of 16-fader Avid S3 control surfaces — one for the musical score from composer Thomas Newman, and the second for dialogue tracks. “Everything on Passengers has a custom-designed sound,” says Files. “We wanted to stay away from anything that sounded stock.”

“We worked through the temp mixes to print mastering totally in the box,” adds O’Connell. “Our Native Atmos mix will then fold down [inside the Dolby RMU] to 5.1- and 7.1-channel mixes” for alternate playback in non-Atmos theatres. “The RMU does a great job of the down-mix; it provides a great starting point,” he says. “We will then finesse the balances and assignments, as necessary — ‘tweak to taste,’ as we say.”

The Atmos mixing was done on the Novak Stage, and the Atmos-compatible sound design was performed at Pacific Standard Sound, Files’ personal facility. “Working Native means that the client can hear our immersive mix right here in the room, as we put sound into the overheads and side channels,” O’Connell says. “Directors know precisely where we are heading. From my perspective, working in the box makes that process so much easier.”

As the Starship Avalon encounters engine failure, a loss of power and, as a result, shuts down the artificial gravity, we hear a complex “stutter” sound, with the music track being augmented with intermittent sound effects modified by Files. “I designed these sounds to signify a failure of motive power and gravity loss as the ship stops spinning,” the supervising sound editor explains. In fact, he used his own processed voice as one of the layers for that sound. “Yes, I actually performed it,” Files continues, “and then phased, flanged and chopped up the sounds before adding overall reverb and ambience. Sometimes using your own voice is the fastest way to get a sound out of your head and onto the screen.”

When the gravity finally fails, Lawrence’s character, Aurora, is doing laps within the ship’s pool; the mass of water begins to rise up with her trapped in the center, fighting for air. “We spent several days to refine that scene, finding the right balance of music and effects as the large mass of water rises out of the pool,” says O’Connell. “We recorded several sounds using underwater microphones,” Files explains, “and processed them in various ways to give the sounds more weight and drama, so that the audience would be able to feel how massive and dangerous this floating water felt to Aurora as she is trapped inside of it.”

“Is that wave a little loud here?” Brandon asks O’Connell and Files. “Is that an option posing as a question?” O’Connell retorts, with a broad grin. Files lowers the wave level on a subsequent pass, but within a half hour the music has been taken back a shade, and now the wave is raised in level again to give it more presence. “In these high-action scenes, it’s always balance between score and effects,” Files offers. “We replay the scene or part of a scene over and over to determine the best dramatic balance, riding the mix until everybody is happy with the result.” At one point while trying out various effects/music balances, and with the sound rising to powerful levels, somebody on the stage says, “I think we’re reaching J.J. Levels!” referring to the high SPLs favored during in-progress mixes by J.J. Abrams while directing his high-action films. O’Connell backs off the playback level, with a knowing chuckle.

Regarding the choice of O’Connell and Files for this project, Brandon recalls that she has worked with both of them before, but separately. “Will Files and I worked together on Star Trek Into Darkness and Star Wars: The Force Awakens. I suggested to Morten Tyldum that we hire him as our supervising sound designer because Will has a unique and modern approach. He’s the greatest collaborator and is always willing to try anything — he’s incredibly inventive — and he rolls with the pressures and last-minute changes on a film as big as Passengers.

“I’ve known Kevin O’Connell for at least 25 years,” she continues. He brings experience and inventiveness to the mixing stage; that’s a fantastic combination and a must for me. He’s able to read my mind even when I can’t quite express I’m looking for in the mix. He’s always able to find a way to work out any problem — and make it seamless.”

Brandon talks mostly in emotional/story terms: “I explain what I want to hear in a scene, the feeling I would like each sound to evoke. Sometimes that comes down to almost no sound at all. The lack of sound and/or music can be very powerful, especially in a big visual effects film. There are times we will thin out music and effects, and then lay them back in one by one so that we can create the feeling we want.”

During this and subsequent scenes, we hear the Starship Avalon make various warnings. As Files explains, the team was looking for a British female voice, “someone you would trust — a pleasant but authoritative voice,” he says. “After unsuccessfully auditioning many voice actors, I was trying to think of where I had heard that kind of voice before. And the London Underground popped into my head. We ended up tracking down Emma Clarke, the same woman who was the voice of the UK’s London Underground, and she is now the voice of the Avalon.”

“In this critical scene, we needed a more aggressive warning of engine failure, which I’ll ‘worldize’ [with realistic ambience] to make it sound more convincing,” O’Connell adds. As Files begins to rebalance the sound of the engine failing, Brandon responds that she liked the shape of it. “It’s a complicated balance with several sound elements,” Files comments as he turns from his Pro Tools screen. “I can go back and refine it later.” Everybody agrees, and the mix session moves on.

Creating Convincing Sounds

During a subsequent telephone interview, O’Connell considered that Files and his post-production team did a brilliant job developing signature sounds for various interiors within the CGI-developed Starship Avalon. “Since the actors were performing against green screen on the set, everything we hear had to be crafted in editorial and then balanced against picture on the stage,” he explains. “We envisioned the spaceship to be like a luxury ocean liner, with the music setting the tone for the big, cavernous interior spaces, plus appropriate ambiences and immersive reverb to establish that sense of an immense structure. Everything in the ship is entirely automated, with high-tech telecoms. Infomat screens are everywhere, responding to questions and providing system alerts. Together with many robots, our challenge was to make it all sound automated — with appropriate robotic voices — but not cold and telephone-like.”

Although Passengers was O’Connell’s first Native Atmos project, he really enjoyed the experience. “It has been one of the most collaborative mixes I’ve ever been involved with,” he enthuses. “I was grateful to be working with Will and his talented team since they have worked in the native Atmos format many times before. They delivered 10 Pro Tools tracks of production dialogue, 10 of ADR, 10 of robots and bots, and up to 10 of atmospheres. Dependent on the scene, music arrived as up to 10 5.1-channel stems — two for orchestral strings and brass, two of low-frequency percussion, two of MF percussion, two of HF percussion, and two of miscellaneous percussion — plus various two-track stems of bass, strings, extras and other elements. We also identified up to eight elements from the dialogue tracks as possible Atmos objects, together with up to 10 from the music tracks, so that we could move these into the side or overhead speakers, as appropriate. In total, we probably had 60 to 70 dialogue tracks, plus 150 music tracks, on the console.”

During pre-dubs, O’Connell says, “We wanted to present to the director our vision of how we thought the ship should sound, and give it a unique character unto itself; we didn’t want it to sound like the Starship Enterprise or the Millennium Falcon, for example. Remaining in the box meant that we could refine everything as we moved through pre-dubs to pre-mixes and then print mastering — which was essential, because we were receiving new visuals right up to and beyond print mastering! For example, we could rethink the robot voices as their CGI elements were refined.”

Files worked closely with two talented sound designers/editors: Phil Barrie and Lee Gilmore. “We used as much original material as possible, opting for newly recorded and designed sounds and not effects libraries,” Files stresses. “We spotted each reel and tried to deliver a mix of early ideas to Morten and Maryann as soon as possible so that we could start getting feedback. In general, I tried to get out of Phil and Lee’s way and let them start developing their creative ideas, then review the scenes with them after they’ve had a pass and talk through notes and new ideas.

“As we were developing the sound palette of the film, we often talked in terms of ‘How should the audience feel about this thing?’ rather than ‘How does this thing work?’ he continues. “I think that’s a much better approach, since sound is such an expressive and emotional medium. Especially in a film like this, where nearly everything is created with CGI, it gives us a huge amount of latitude to create sounds that are stylized and part of a cohesive vibe. It’s a lot like working on an animated feature, since all we really get from the set is the dialogue.”

The supervising sound editor wanted the ship interiors to sound “very elegant and classy with fresh sounds of high-end, high-tech, non-threatening hardware — maybe as if Apple had made the Starship Avalon!” he says. “It was all about product design; how would it sound, in a unified way? We carefully developed sophisticated-feeling sounds for the lights turning on and off, for example, together with motors in the elevators and other mechanical systems. The ship has no hard edges visually so we tried to extend that aesthetic into the sounds; we looked for softer but weighty sounds, trying to strike the balance between delicate and industrial to retain that high-quality feel of the ship on the soundtrack as well, with maybe a musical tone to it, to enrich ‘the passenger experience’ that the ship’s designers might have wanted.”

For sounds of the ship engine, various motors and other technology, Files did not use any real-world sounds. “Since the film is set hundreds of years into the future, it wouldn’t sound like what we currently know about,” he says. “So we tried to move beyond typical servo motors and look for new motor sounds, using synthesizers and samplers to create musical noises and manipulate them to sound like real objects. We also used unexpected sound sources for some of them: slowed-down chair squeaks; a cardboard box sliding on a wooden floor; rolling metal cups and glasses around a table top to see what they sounded like; and we even used the sound of the new cylindrical Apple Mac Pro rolling on a glass table as one of these spaceship motor elements. The robot motors were also derived from musical tones, to create a unique voice character for each one, sometimes using non-steady modulation and maybe slowing it down to half-speed to add an imperfect ‘personality.’” Such engine sounds also needed to co-exist with Newman’s powerful percussive score.

Files recalls that he developed a total of 24 multi-channel pre-dubs with suitable Atmos objects. “I had 16 sound effects, two Foley and six background pre-dubs, with a total of 24 objects,” he explains. “Each pre-dub was 7.1-channels wide.” Other sound professionals working on the project included co-supervising sound editor Andy Sisul, sound effects editors J.M. Davey and Chris Terhune, dialogue editor Hugo Weng and music editors Maarten Hofmeijer and Bill Bernstein.

Robot and Machine Vocals

As ADR supervisor, Kizer was responsible for wrangling the various robot and machine voices. “Initially, we had a list of 21 potential voices,” he recalls. “But the director narrowed that down to eight or nine, to provide a sense of cohesion. I set up 126 separate voice auditions and then reduced that to a short list of 60. Will Files and I whittled it down to 30 and the director selected the final voices. We walked a fine line between real and artificial voices, because in the future it might be possible to synthesize something a little more human-like than we can now. Among our criteria was that it should be hard to tell that the film’s characters were taking to a machine.”

Aside from an ADR session on the West Coast, the ship’s voice, provided by Emma Clarke, was recorded in her home studio and sent over from the UK the next day as digital files, with different readings that the director either liked or rejected, according to Kizer. “For the other voices, the rule was simple: no monotone — a normal cadence — with just a hint of robot or artificial intelligence inflections,” he explains. “We looked for a certain quality in the voice and then worked on its delivery.”

During early picture editing, some of the robot lines were passed through Apple’s text-to-speech app as a guide. “It was a cool effect that worked quite well,” Kizer acknowledges. “But because of clearance rights, we couldn’t use the results in the film. In the end, Morten almost exclusively elected to go with American male voices for the robots.”

“We treated these voices, plus various helmet sounds, with multiple [Audio Ease] Speakerphone plug-in settings and variable layers of Futz,” O’Connell explains. “We used various combinations to achieve the right amount of processing on each voice. During the louder scenes, we backed off the Futz because the effect can end up sounding too much over the top.” He also recalls that, per the director’s choice, “We did not treat Michael Sheen’s voice” for his android character.

Summarizing the team’s experience on Passengers, Brandon concedes that humor formed a great lubricant. “We laugh a lot, she says. “Because this work is really tough, if it wasn’t for the post-production crew, I think I’d lose it. Laughing frees up my mind to be creative.”