by Kevin Lewis

Television kept post-production people employed during the post-World War II years in New York. Feature film was a West Coast commodity, but the Madison Avenue advertising firms, such as J. Walter Thompson, Benton & Bowles and Hill & Knowlton, among others, were a major part of the “go-go” years in Manhattan. Editors in the East Coast Motion Picture Film Editors Guild, Local 771, which was founded in 1943, were the backbone of the advertising and television industry, working under heavy pressure to meet television deadlines in the news, taped shows and commercials divisions.

Charles “Jerry” Bender and Bernice Steinberg were two conspicuous players in the advertising world. Mili Lerner Bonsignori was a primary editor for the Edward R. Murrow documentary and news unit at CBS-TV, and Geraldine Lerner was an editor in the small feature film industry left in New York. As CineMontage discovered, all four had exhibited extraordinary initiative, often transcending the job classification of film editor into exploring the possibilities of sound editing and re-recording mixing. They were also early members of their Local.

Director Joseph and his wife Geraldine Lerner were independent filmmakers in New York with their Laurel Films in 1947. From her home in New Jersey, the 98-year-old Geraldine, always called Geri, recalls, “We [Laurel] were the only ones producing theatrical films in New York at that time.”

Before he was drafted into the Army during World War II, Joseph had been an assistant director at RKO on the West Coast, with credits like Gunga Din (1939). He was assigned to make Army Signal Corp films at the former Paramount Astoria Studio (now Kaufman Astoria Studio) in Queens, New York. He enlisted such movie actors as Jack Carson, Bert Lahr, Zachary Scott and Faye Emerson to star in his films while they were performing in Broadway shows.

Geri, who edited Signal Corps films during the war, later worked on both coasts for MGM dubbing foreign-language films. She joined Local 771 in early 1946. Between 1949 and 1951, they produced four well-regarded independent films that were completely union-made. Their first film was The Fight Never Ends (1949), an African-American film starring boxing champion Joe Louis and Ruby Dee, followed by the film noirs C Man (1949) and Guilty Bystander (1950), and the comedy Mr. Universe (1951), featuring Vince Edwards.

Geri was her husband’s picture, sound and music editor. She loved working with sound and believes she was the first to work with magnetic sound in New York. Laurel’s films were distinguished by outstanding music scores — unusual in low-budget filmmaking — because Geri could break down a score for scene purposes and time it without distorting the composer’s intentions. One of her proudest achievements was her music editing of the Gail Kubik score for C Man, starring Dean Jagger. Kubik was a Pulitzer Prize-winning composer, which was a coup for the Lerners. Geri herself was a musician and a trained mezzo- soprano.

“My husband would only employ union people,” she remembers, adding that the great Dede Allen got her start as a script girl at Laurel. During the House Un-American Activities Committee and blacklisting era, Joseph would hire blacklisted actors for crowd scenes. According to Geri, it was almost guerrilla-style filmmaking. “We would shoot in the streets and in abandoned warehouses,” she says.

By 1954, they were working in Italy, where Joseph directed the Italian television series The Three Musketeers. When they returned to New York, Geri freelanced in television and film, when she wasn’t editing her husband’s films. She also worked at CBS, where her sister-in-law Mili was employed.

Joseph encouraged his sister Mili — now Mili Lerner Bonsignori — who had edited for him at Laurel, to become an assistant editor. She joined Local 771 in 1948 and, soon after, was recruited by editor Gene Milford to work for CBS as an editor. She struck gold and became Edward R. Murrow’s editor on See It Now (1951-58), the innovative news show that was the granddaddy of CBS Reports (1959-92) and 60 Minutes (1968-present).

Only three editors cut that incredible footage of social, political and cultural movements during the Eisenhower Cold War years. “I loved film and felt it was alive in my hands,” Bonsignori recalls. “It spoke to me; videotape did not.” Murrow and fellow producer Fred Friendly never came into the cutting room, she claims. “Fred would stand in the doorway and say, ‘How long?’ They respected their editors, and always said, ‘That’s where the power is.’ We screened the dailies, discussed the story and went into the cutting room. We screened again, corrected, wrote the script, laid track and went on the air.” She was a picture and sound editor and says she built as many as five tracks for her shows.

“William Paley, president of CBS, said he got a stomach ache every week that See It Now was on the air,” Bonsignori remembers. “And we were on the air for seven years! We also caused severe headaches for management when Murrow exposed Senator Joseph McCarthy in 1954. Murrow had the courage to show McCarthy for the threat he was to our civil liberties. It gave Congress the courage to put him on trial and defeat him. It also cost us our sponsors; they didn’t renew.”

Bonsignori remained at CBS after Murrow left in 1961, when he was appointed director of the United States Information Agency by President John F. Kennedy. She edited many CBS Reports. That series’ documentary Hunger in America (1968) crystallized for her the political and social power of editing.

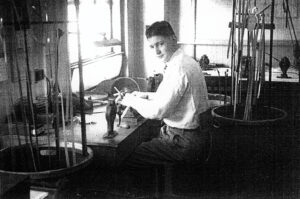

Photo courtesy of Mili Bonsignori

“A baby died of starvation while the cameras were rolling,” Bonsignori recalls. “I was so shocked that I let the film roll. The impact was so overwhelming that a dismayed America demanded an answer. CBS was sued by the Department of Agriculture. The baby’s parents claimed that the baby did not die and that the film was manipulated. But I saw the baby die.” According to her, every cut in the film was examined during the court case, but no manipulation was found, and she was not called to testify.

From around 1965 on, when Bonsignori left CBS, she was a freelance editor at ABC, Children’s Television Workshop and Home Box Office. She also served as a vice president of Local 771 in the mid-1970s. She retired in 1984, and at 93 lives in Florida. Looking back on the social potential of that first decade of television, and recalling holding the pivotal events of the world in her hands, she says, “I thought we would change the world.” And to a certain extent she did.

Bonsignori was close friends with Charles “Jerry” Bender at CBS. Bender entered the film industry as a can carrier at WPIX-TV soon after his high school graduation in 1948, and eventually became an assistant editor at the New York television station that year, joining Local 771 in 1949.

After five years at WPIX, Bender was hired as an editor on Adventure with Charles Collingswood by Jack Bush, then the head of the film department at CBS. Robert Northshield was the producer and was instrumental in shepherding Bender’s career. After Adventure (1953), Northshield hired him for The Seven Lively Arts (1957), which was executive produced by John Houseman. Another notable credit was Here is New York (1957), adapted by Andy Rooney from the E.B. White material.

Over the next few years, Bender says, “Northshield and I did a lot of jobs together. We went on location for shows and documentaries. I was an editor but I did everything including sound and sound effects.”

After CBS, Bender freelanced at Screen Gems, which was operated by Ralph Cohn, the son of Jack Cohn, co-founder of Columbia Pictures with his brother Harry. These were invaluable years for the editor. “Houseman would stand by my Moviola at CBS and would criticize my day’s work,” he recalls. “Cohn would criticize my editing every day at Screen Gems. I learned from him and from Houseman how to organize and construct a story.” If he had the luxury of a time schedule, he said, he would not make a cut immediately, but instead would think about the editing construction overnight.

Bender remembers that CBS in the 1950s had a curious production organization; it had small studios all over Manhattan. He was disappointed to learn that one of those studios, which was on the upper floor of Grand Central Station where such legendary CBS shows as You Are There (1953-57) were produced, was now a tennis court. “CBS rented studios, rather than buy or build, because they didn’t want to have buildings they couldn’t sell,” he says.

Finding and keeping editing jobs on the open market was uncertain back then and Bender recalls his excitement at landing a major editing contract, and telling editor Dede Allen about it. He says Allen told him, “Bender, you know you have the job when you see the dailies on the table.”

He also worked in London and on the West Coast. He and a partner opened an editing house in the 1960s and, in 1972, Bender opened his own solo business. He retired around 20 years later as digital editing was taking hold. Among his pleasant memories is the series of Volvo commercials he edited for Swedish director Bo Widerberg, which featured the ominous voice of Max von Sydow. At 82, Bender can still imitate the low, Swedish monotones of the acclaimed actor. When asked about difficult assignments, he shakes his head and says, “I never lookedatitthatway.Theworkwasn’tdifficult;the clients were difficult.”

Bernice Steinberg was a dynamic force in the advertising industry and was an innovative pioneer in television commercials. From her home in Florida, she looks back on her career and says that highlights included “creating commercials that were deemed worthy of inclusion in the book The 100 Best TV Commercials, and working with a lot of very talented people.” Among the classic commercials she helped to create were the animated Bert and Harry Piel (comedy duo Bob and Ray) for Piel’s Beer, Alka-Seltzer’s “Spicy Meatball” and Wendy’s “Where’s the Beef?”

She joined the Guild in 1944 when she was at Paramount’s New York animation studio opaquing cels for the Popeye cartoons. Steinberg was so efficient that she was recommended as an editor by composer Winston Sharples. “I became a film editor in 1947 because I seemed to be able to do that with ease,” she recalls. “I got a good start as a member of the Guild.”

When television needed commercials by 1949, Steinberg was ready because she understood animation and design. “I was very proud of being top-notch at editing commercials, and it led to my opening my own business in 1950,” which was the Ani-Live Film Service. “I had no trouble attracting clients.” She jokes that she still has the whip with tails that she cracked the floor with to “motivate” her employees. “Come on, we’ve got to get this job out!” she’d purportedly say.

Indeed, most of the biggest Madison Avenue advertising agencies made a pilgrimage to her offices. Because she was a player with the real “Mad Men” of advertising, she was able to help many editors and post-production people get their feet in the door. Among her many accomplishments were her pioneering hires of African-Americans in that pre-Civil Rights era.

Steinberg, now 84, always came through for her clients. “The biggest challenge,” she says, “was dealing with time deadlines.”

Some things never change.