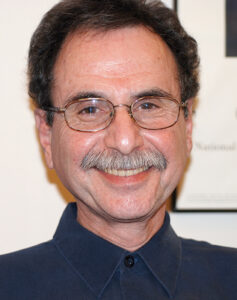

Editor’s Note: With the recent passing of award-winning editor Richard Marks, ACE, at the age 75 on December 31, 2018, we are re-posting this interview with him from the March-April 2013 issue of CineMontage on the occasion of his receiving a Career Achievement Award for the American Cinema Editors.

by Peter Tonguette

Not long ago, Richard Marks, ACE, sat down and began watching his old movies — not just his best-known movies or his personal favorites, but all of them. The four-time Academy Award- and ACE Eddie Award-nominated editor says it was “a strange experience” to be reminded of the tens of thousands of decisions — large and small — that he made in the cutting rooms of such films as Apocalypse Now (1979), Pennies from Heaven (1981), Terms of Endearment (1983) and As Good As It Gets (1997).

“Once you’ve committed to something, the next time you look at it, you say, ‘Gee, maybe that was the wrong decision. Maybe I should’ve done it that way,’” Marks comments. “So you’re always re-cutting… I’m always recalling what a lot of the alternatives were.”

It was the news that the American Cinema Editors (ACE) had selected him for a Career Achievement Award that prompted Marks to revisit his life’s work. He volunteered to assemble the reel of highlights ACE showed at its February 16 ceremony — “probably out of some masochistic tendency,” he jokes.

Even so, the process reminded him of his unassuming beginnings. The New York native graduated from City College of New York without a clear notion of what he wanted to do next. As he remembered, “Serendipitously, a friend of mine — all of us being in the same state of confusion — said, ‘Well, you like the movies. Why don’t you get into the movies?’” He worked for a spell at a commercial and trailer editorial house in New York as a “glorified schlepper with a college degree,” but the experience was valuable because it exposed him to the world of editing.

Then Marks got his big break: an offer to be the sound apprentice to then-sound editor Alan Heim, ACE, on Rachel, Rachel (1968). The picture editor was Dede Allen, ACE, who subsequently hired Marks as an assistant editor on Arthur Penn’s Alice’s Restaurant (1969) and then as an additional editor on Penn’s Little Big Man (1970). Only a few years later, Allen and Marks worked together as colleagues on Sidney Lumet’s Serpico (1973). “You always felt a little strange all of a sudden being a peer with your teacher,” Marks notes. “But Dede was great.”

In the years that followed, Marks saw the maturation of other early relationships. He first worked with director Francis Ford Coppola as an assistant editor on The Rain People (1969) before working as one of three editors on The Godfather: Part II (1974) and then as supervising editor on Apocalypse Now. Three of his Oscar nominations came on films written and directed by James L. Brooks, who has collaborated with him exclusively from Terms of Endearment (1983), their first film together, to How Do You Know (2010), their most recent.

On learning of the ACE honor, Marks was surprised and flattered. “It’s wonderful to have the recognition of my peers,” he comments, although he also found it bittersweet because, “It just reflects how many years I’ve put into this.” While Marks has not yet officially retired, he has cut back on what he calls the “craziness of the hours and the jobs.” One thing is for certain: He could do worse than to spend his extra downtime watching his old movies. CineMontage interviewed Marks in January.

Richard Marks: God was on my side. What can I tell you? At the end of Rachel, Rachel, she had an offer to do Arthur Penn’s film. The assistant and the apprentice she had been working with decided to go off on their own ways. And so she was without a crew. I just made a bid for the job. I told her how much I wanted to work with her. She knew what experience I had. I don’t think there was that division that you often hear about in Hollywood — that if you worked in commercials or trailers, you were automatically slotted into that position.

I think New York was a lot freer in that sense. If anything, going through commercials and trailers just meant you went through the process more times, more quickly. Going into a feature there were different skills one needed, but they were certainly not unlearnable. So I lobbied very hard for that job with Dede. I called everyone I knew who knew her and I begged.

CM: You had a lot of moxie.

RM: Blind ambition, fearlessness and the stupidity of my youth. But I did get the job. Years later, I asked Dede, “How come you decided to go with me?” This was like the great job in town; everyone was after it. She said, “Well, you know, during the sound mix of Rachel, Rachel, every time the film ripped in the projector, you shot out of your seat. You were the first one back there repairing it. I figured anyone who can work that way, and understand that we have to keep the film going, is someone I should at least try working with.”

CM: A year later, you were an additional editor on Little Big Man.

RM: I was. Dede needed it. She was overwhelmed with material. It was a very big project. She was a very gracious, trusting woman, who said, “Do you want to give it a try? I have to go out to Montana to the shoot. Here’s a scene to cut.” We talked about the scene and we screened dailies together. She went away for two or three weeks and I was in a state of nauseous terror, cutting and re-cutting and re-cutting… I don’t think I ever left the cutting room. Dede came back and I showed her the cut. She had a wonderful, wonderful personality and instinct for teaching and a love of it.

CM: What can you say about Francis Ford Coppola?

RM: He’s an amazing director, an amazing mind and an extremely wonderful writer. You find that certain directors are very controlling and straightforward, and certain directors need a certain environment of chaos. And in some ways, Francis needs, or needed, an environment of chaos. He would jump into these projects.

CM: What are your thoughts on your collaborations with James L. Brooks?

RM: We found ourselves to have kindred spirits and kindred senses of humor. I think for Jim it was the first time he had worked with an editor outside of the parameters of television, where the relationship with editors is appreciably different. So he was exposed to the big-mouthed, opinionated mea. There was something useful in that I wasn’t shy about expressing what I thought was wrong. If I had an idea of how to fix it, I would say, “This is my idea.” But, as with any good editor, ultimately, it’s not your movie. It’s the director’s movie, and the final decision will be made by him. But my job as an editor is to present options.

CM: In the 1980s, you began working as a co-producer or associate producer on films you cut, and you even directed second unit on Warren Beatty’s Dick Tracy (1990).

RM: At the midpoint in my career, I sort of had to make the decision of whether or not I wanted to pursue directing. I really decided that wasn’t what I wanted to do, that I enjoyed editing too much. I like the quietness of the cutting room. I didn’t like having a hundred people throwing questions at me all at the same time. I could do my best work in an editing room.

The expansion you talk about has more to do with — certainly in the producing end — controlling the area in which I work. So that every expenditure, every decision that’s made about post-production, is not made solely by someone else, but that the editor also factors into it.

Regarding the second unit direction on Dick Tracy — Warren is an amazing man. You walk in, you’d be having a conversation, and he’ll say, “I need a second unit director for the shoot-’em-up. Think you can do it?” And that’s all you have to say to me: “Think you can do it?” “Of course!” That’s how I was directing second unit on Dick Tracy.

CM: Since the mid-1990s, you’ve also taken editorial consultant and additional editor credits on several films. Do those jobs flex your muscles in a way that is useful?

RM: Well, they do in the sense that they give you a different perspective. Coming in and being critical of a work that already exists just allows you to see it differently. And God knows part of the editorial process is the constant inability to remove yourself from what you’ve done, to try and find some objectivity, and to figure out what the problems are. Being brought in to look at a problem sequence or to re-cut something from a fresh perspective is a very revealing experience to look at what someone else has done, how they conceived it, and why they did what they’ve done. You can walk into a situation where you look at an editor doing a cut, but you can’t really be judgmental, unless you know what they had to work with.

CM: What has changed most in editing since you started?

RM: Well, one large part of this is Dede spearheading editors getting a lot more credit for the work that they did. She pioneered that area of solo credit and promoting the idea of how important an editor was. That happened to coincide with a change in American cinema, where not just the tone of what was being committed to film, but the technology of film was changing. So, it was no longer setting up a camera that was locked into one position, doing one or two takes, having plenty of time to rehearse a shot 60 times, and then shooting it. The economics of the industry and the technology in the industry started to erode that way of doing work.

About the time that I started working in movies, directors started shooting a lot more film, a lot more coverage. They could because it was physically doable. It was not that expensive, relatively. The shooting day was more expensive than the cost of exposing more negative. The tools started to change. You weren’t locked down shooting optical tracks. You were all of a sudden shooting on tape. Your audio was on tape. It started to allow you incredible flexibility. That flexibility meant more options. Those more options had to be put together at some point.

The more options you have, the more decisions you have to make. In the editing process, it’s about making decisions, committing to it at least temporarily, and moving on. I mean, how many possible ways can you put something together? Millions. The more options you have, the more often you can get yourself into trouble.

CM: Well, that’s why they hire Richard Marks — to get themselves out of trouble, right?

RM: It was a very funny thing when I first started editing. You start looking at the material and saying, “Well, I could do it this way or I could do it that way.” You read the script and say, “Well, the script wants you to do this and this and this. But that’s just literally. Maybe if you’d approached it that way and that way and that way, you get to the same place.” You start driving yourself so mad that you can’t make the first cut.

It’s funny, I had this discussion with my wife the other night. She, too, is an editor. I said to her, “On every film I’ve ever done, the first scene that I cut is like a barrel of indecision.” Like, where do I make that first cut? What am I committing to? And then, finally, I say, “Stupid, just commit to something.” You can always change it.