by Calvin Yocum

When I was a teenager in the 1960s, my father and I were separated by a stereotypical generation gap and several other gaps unique to us. He was a Dust Bowl immigrant who barely made it through high school, and I was some kind of anti-establishment egghead. Nonetheless, we always found common ground watching John Wayne movies.

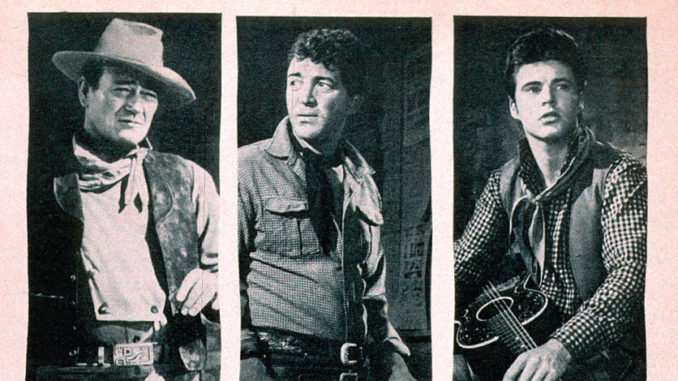

Rio Bravo, a Western directed by Howard Hawks, was my favorite. In a strange way, watching Rio Bravo was like taking communion in church. By consuming the wine and wafer, we vicariously channel the divinity of Christ, and, by watching Rio Bravo, I was vicariously channeling the courage of John Wayne. I watched it so many times I had memorized the entire movie by the time I graduated from high school.

As a freshman at Yale College, I didn’t dare admit I was a fan of either John Wayne or Rio Bravo. Wayne, who had just done a very pro-Nixon, pro-Vietnam War interview in Playboy, seemed utterly out of touch with my anti-Nixon, anti-war generation. It was both politically and intellectually safer to align myself with the European cinema. For a movie to be art, I figured it had to be turgid and inaccessible. American movies were way too much fun to be art.

Since absolutely no one on campus owned a TV, I gravitated to the Yale Film Society at least two or three nights a week. For an admission price of around a dollar, I got to watch scratchy 16mm prints of vintage films, both European and American, in a converted lecture hall. It was a great introduction to directors like Bergman, Kurosawa and Renoir, but I was also exposed to Hawks, Ford, Huston and Wilder. When Rio Bravo was screened on a rainy Wednesday night, I didn’t expect anyone else to show up. But, to my astonishment, every seat was filled. People even sat on windowsills and the floor. Even more miraculously, we all spontaneously started reciting dialogue in sync with Wayne, Walter Brennan, et al. It was an intoxicating communal experience.

Armed with a new framework for appreciating the artistry of Howard Hawks, I finally started to understand how my childhood exposure to the movies of the 1930s, `40s and`50s had shaped my personality, my value system and even my sense of humor.

I was amazed to be among a large group of people who obviously loved Rio Bravo as much as I. The diverse collection of fans crossed all social and political lines. On the way out, I ran into a couple friends and, over coffee, we discussed the movie in the same analytical way we’d deconstruct a Henry James novel in an American Lit class.

We talked about the themes linking Hawks action movies like Only Angels Have Wings, Red River and, of course, Rio Bravo: redemption, the dynamics of male bonding, and performance under pressure. One of my friends mentioned Hawks’ influence on the French New Wave directors. Indeed, Jean Luc Godard called Rio Bravo “a work of extraordinary psychological insight and aesthetic perception.” Godard wrote, “Hawks has made his film so that the insight can pass unnoticed without disturbing the audience that has come to see a Western like all the others.”

In other words, Rio Bravo really is art, but Hawks’ seemingly casual, straightforward storytelling allows it to pass as popular entertainment as well. In a sudden epiphany, I realized that art doesn’t have to be expressed in some kind of tortured code that only the educated elite can decipher. The truth and relevance of the message are more important than the mode of expression. The beauty of a movie like Rio Bravo is that both a simple blue-collar guy like my father and a brilliant French director like Jean-Luc Godard can derive the same message. And they can both have a good time in the process.

Armed with a new framework for appreciating both the artistry and craft of Howard Hawks and the other great American film directors of his generation, I finally started to understand how my childhood exposure to the movies of the 1930s, `40s and `50s had shaped my personality, my value system and even my sense of humor. Since these movies also connected me to my parents, I gained a sense of cultural continuity that helped shrink that generation gap.

As a story analyst, I’ve had the opportunity to work on a number of movies with serious artistic aspirations, but I’m just as proud to help crank out popular entertainment. In both cases, the goal is the same: linear, coherent and efficient storytelling. I own Rio Bravo on Beta, VHS, laserdisc and DVD. Every new viewing of the movie still magically echoes each precious time I watched it with my father in the 1960s and the time I saw it through new eyes at the Yale Film Society. Nothing else in my life resonates quite the same.