By Peter Tonguette

“Hit Man” might be called a movie defined by its improbabilities.

The comedy stars Glen Powell as Gary Johnson, an even-tempered, profoundly square philosophy professor in New Orleans who is tapped for an unusual assignment: the New Orleans Police Department wants him to present himself as a hit man offering his services during sting operations. That the dweebish Gary could be considered for such an assignment is improbable, but he settles into the role and relishes its many disguises.

Perhaps equally improbable is the film’s director, Richard Linklater. An icon in the independent film world for such charming, low-key, discursive movies as “Slacker” (1990), “Before Sunrise” (1995), “Waking Life” (2001), and “Boyhood” (2014), Linklater finds a fresh new tone—tightly plotted but broadly comedic—in “Hit Man.” Co-starring with Powell—who had earlier appeared in Linklater’s “Fast Food Nation” (2006) and “Everybody Wants Some!!” (2016)—are Adria Arjona, Austin Amelio, and Retta.

“Hit Man”—which Linklater and Powell co-wrote based on a nonfiction article in Texas Monthly—premiered on Netflix on June 7. The movie has already opened in select theaters.

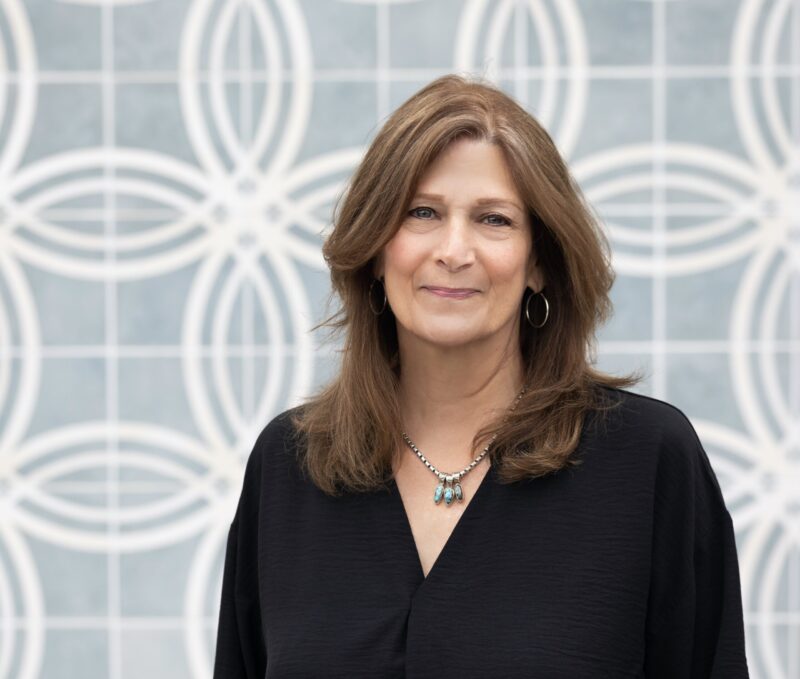

Most improbable of all, though, may be the nearly career-long collaboration between Linklater and the film’s editor, Sandra Adair, ACE. The picture editor has edited all but one of Linklater’s feature films since first working with him on his sophomore effort, “Dazed and Confused” (1993). A native of Carlsbad, N.M., who was raised in Las Vegas, Nev, Adair pulled up stakes for Austin, Texas, in the early 1990s—which happened to be the longtime base of operations for Houston native Linklater. (As it happens, Powell was also born and raised in Austin.)

CineMontage recently caught up with Adair, who talked about “Hit Man,” her rapport with Linklater, and the view of Hollywood as seen from Austin.

CineMontage: Sandra, what took you to Austin in the first place?

Sandra Adair: Well, I met my husband [director Dwight Adair] in Austin in the 1970s. We moved back and forth between Austin and Los Angeles several times, but we did settle in L.A. for many years. I worked as an assistant editor for about a decade, and in the early ’90s, it was hard to get work. My husband and I were sort of like: “You know what? If we’re going to be starving, we might as well starve in Austin, because we’d rather raise our kids there anyway.” We came here just with the hope that we’d figure out something.

CineMontage: Once you made the move, how did “Dazed and Confused” come your way?

Adair: When I lived here in the mid-70s, I worked on a film called “Outlaw Blues” as an assistant for the editor Danny Greene. At that point in Austin, there was one post-production facility, the Texas Motion Picture Service. When we moved back here in the ’90s, I contacted the owners and said, “I’m back and I’d really like to get into film here. What’s happening in Austin?” They told me about “Dazed and Confused.” I tracked down the address for the production office and I wrote a snail-mail letter of introduction with my resume. Three weeks later, I got a call from the producer for an interview. Rick was in full-blown pre-production. There were already people walking around in costumes. I had a pretty short interview with Rick, and he said, “You’re going to have to go out to L.A. to meet with the producers.” I did that, and then I got the job.

CineMontage: Did you edit “Dazed and Confused” at the Texas Motion Picture Service?

Adair: That is where we edited—on film, obviously. It was all cut on a KEM, but for a first cut of some of the montages, we used an editing platform called the EMC2. It was one of the very first nonlinear systems, and I had actually worked on an EMC2 project right before leaving L.A. I was comfortable with that.

CineMontage: “Dazed and Confused” must not have been the easiest project on which to begin with a new director.

Adair: It wasn’t. It was a learning curve for both of us, and Universal put us through the paces with a lot of previews and a lot of “Try this” and “Try that.” It had a really long running time at first, and so we had to get in there and really squeeze it together. Sadly, we had to lose some of the story of some of the lesser characters, but we managed to pull it together. And Rick really stood his ground on the things that he thought were important.

CineMontage: Does whether or not you preview one of Rick’s films depend on the project and perhaps the budget?

Adair: It depends on the project. For me, the preview process is helpful, especially on a film like “Dazed and Confused” or “Hit Man.” If there’s a good level of comedy or humor involved, you can’t really judge that when you’re sitting in a room by yourself. You’ve got to be able to measure if the jokes are landing, if the story is landing, if all of the elements are lining up the way you imagined that they will.

CineMontage: Have you ended up editing most of Rick’s films in Austin?

Adair: Yes, Rick has an office where I have a cutting room. I’ve edited almost every single film of his at his office, unless we were on location during production. Then I would be on location with him at a studio or at a facility, and then we would come home to do the director’s cut. For a few of the films, we’ve gone back to Hollywood to do the finishing: the sound mix and the color.

CineMontage: Do you go on location all that much?

Adair: No, and I wasn’t on location for “Hit Man.” Post-pandemic, I think the secret is out that you can just work remotely. They would much rather have the extra money to put on the screen rather than have an editor on location when they know damn well that I can put together the first cut without even talking to Rick. We have such an incredible system going.

CineMontage: What is your system?

Adair: It’s the same as what other people do, I’m sure. We have talked about the importance of a really good script supervisor, and I want him to communicate his select take or takes to the script supervisor. He wants to know, even when he comes into the editing room, what his select takes were on the day. I don’t tie myself to that, but I watch his select takes and I can pretty much figure out what he’s going for.

CineMontage: How does the process work once shooting has wrapped and he’s in the cutting room?

Adair: We screen the film together in the room, and then we jump in. He gives me the big notes first, and then we talk about whether there is anything that needs to be shifted in terms of the continuity of the film. And then we just slowly go through these rounds of notes, and we eventually get down to the nuances of the performance in one take versus another take.

CineMontage: Does Rick shoot a lot of takes?

Adair: It depends on the projects, but some of the films where you might think there are a lot of ad-libs, there are none. He works out the scripts before he ever brings a camera to the project, and he’s very certain what he’s going to shoot and the actors are very clear about who their characters are. On “School of Rock,” when I found out that Jack Black was going to be the lead, I thought, “This is going to be wild because we’re going to have so much improv.” Well, there wasn’t any—there was very little, I would say. Jack would bring so much variety to every single take, and yet he nailed it every time—every word in the script.

CineMontage: What excited you about “Hit Man”?

Adair: First of all, I’ve known Glen Powell for a while. I spoke in his creative writing class when he was in high school. I thought he was a real standout actor in “Everybody Wants Some!!” I was really excited to see what he was going to do with this script, and the script was so good and so funny: lots of twists and turns. The whole goal is to tell the story in a way that the audience never gets tripped up. If you can keep an audience connected to the character and the story, and not lose them on pacing, then you’re doing your job well.

CineMontage: Are there any scenes you’re particularly proud of?

Adair: The disguise scenes were the most challenging. Each of those scenes were written longer than they ended up being in the final version, and for the sake of pacing, those required a lot of work. We moved some of those around from where they were originally written. That was to help with the passage of time and Gary’s growing ability to transform himself. I wanted to try to extend the amount of time that he was doing that.

CineMontage: Did “Hit Man” benefit from preview audiences?

Adair: It did. I think one of the biggest challenges was setting Gary up as the nerdy guy at the very beginning so that when he has his very first hit man encounter, you really want to see that he has changed in a heartbeat. With a snap of the fingers, he has altered his personality. We worked on Gary’s introduction in the movie, and I think that came about as a result of a few screenings.

CineMontage: Sandra, what are the advantages to working in the industry from Austin?

Adair: There are many fewer distractions, and it’s very laid back—very, very laid back. We do have a sound supervisor here that we work with again and again, and composer Graham Reynolds, who’s composed the scores on a lot of the films, lives here in Austin. I do miss being part of the editing community in L.A. I see that the holiday party at ACE is happening and I’m like, “Golly, I would love to go to that.” I will say that over the years, I have trained some of the best assistant editors ever—and most of them have come out of the University of Texas.