by Edward Landler

In our last thrilling installment: The low-budget fodder of picture show entertainment from the 1920s through 1940s was miraculously transformed during the childhood years of America’s post-war baby boomers. The conquest of the American home by the television set reshaped cliff-hanging episodic serials and B-movie feature series into weekly hour and half-hour episodic TV series.

They survive today on network, cable and satellite TV channels. The TV series has achieved a day-to-day cultural presence that even allows viewers to absorb its current permutations on web streams into home entertainment systems, computers, iPads and smart phones.

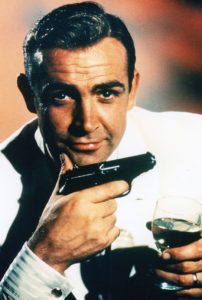

Meanwhile, the movie industry now derives a huge percentage of its profits from audiences flocking into theatres to see countless feature series and sequels. The vast majority of these features are no longer low-budget B-movies consigned to critical indifference. They are major-studio, big-budget fare dominating the world movie marketplace. And it all began with Bond, James Bond.

America’s first introduction to Ian Fleming’s British spy was actually on television in 1954. The year after the first Bond novel, Casino Royale, was published, the CBS dramatic anthology series Climax aired a 60-minute adaptation. While Peter Lorre’s ruthless Le Chiffre was faithful to the original, the show cast Barry Nelson as an American secret agent named James Bond.

Now the longest-running movie franchise — going 51 years since 1962 with no end in sight — the Bond film series was founded in the United Kingdom, where the film industry prospered with a resurgence of series films in the 1950s. Among these series were the Carry on… comedies, starring its stock company of music hall-style buffoons and buxom babes making fun of every conceivable movie genre. Running 34 years from 1958 to 1992, these 31 low-budget films comprise, after the Bonds, the second-longest continually running film series of all time.

At the same time, three science-fiction thrillers (1955-1962) about the eccentric Professor Bernard Quatermass, based on three BBC-TV serials (1953-59), brought Hammer Films its highest box office returns up to that point. Then Hammer produced an even more successful horror line, featuring vivid and gruesome gore: The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) followed by six sequels (1959-74), Dracula (1958) with eight sequels (1960-74) and The Mummy (1959) and its three sequels (1964-71).

The British government fertilized the environment for movie series by subsidizing filmmakers to produce work with British casts and crews. That’s why American Albert Broccoli and Canadian Harry Saltzman’s Eon Productions came to England in 1962 to make the first Bond film, Dr. No with Sean Connery, on a low budget. Its international success led to 22 more films with ever-increasing budgets and eventually four more actors following in Connery’s footsteps. Two other major Bond movies were produced by others outside of the official series: the misbegotten parody of Casino Royale (1967) with David Niven, Peter Sellers and Woody Allen all pretending to be 007 with five credited directors at the helm (including John Huston) and, in 1983, the aptly titled Never Say Never Again with Connery returning to the role 12 years after he left the franchise.

Fleming fashioned his rugged yet suave hero after “Bulldog” Drummond, the gentleman adventurer of H.C. McNeile’s action stories of the 1920s and ‘30s, which were the basis of 23 movies made in the US and the UK between 1922 and 1969. Spicing the action with exotic international intrigue, Fleming also exploited elements of sexuality and sadistic violence. With tongue firmly in cheek, the producers of the Bond movies crafted the erotic and violent images to resonate with audiences of the 1960s and ‘70s.

Paramount Pictures/Photofest

The effects of the movies’ success were immediate and long lasting. Two TV spy series on British TV before Dr. No found their way to American television: the gritty 30-minute Danger Man (1960-62) starring Patrick McGoohan, which was expanded into 60 minutes and retitled Secret Agent (1964-68) for the American market; and The Avengers (1961-69), a spy satire that made a star of its female lead from 1962 through 1964, Honor Blackman. Clad in provocative tight-fitting leather from head to toe — recalling Musidora’s shocking (for its time) costuming as Irma Vep in the ground-breaking French serial thriller Les Vampires(1915) — Blackman donned similar togs as Pussy Galore in the third Bond film, Goldfinger (1964). Her equally leather-clad Avengers successor from 1965 through 1968, Diana Rigg, went on to star in the sixth Bond film, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969).

Since 1962, virtually all spy genre series can be attributed to the Bond influence. First came three Harry Palmer films (1965-67) with Michal Caine, based on Len Deighton’s novels; Dean Martin in four Matt Helm movies (1966-69), based on the Donald Hamilton books; and James Coburn in two Derek Flint spy spoofs (1966 and 1969). Meanwhile, American TV launched The Man from U.N.C.L.E. (1964-68), with some episodes edited into eight movies for foreign theatrical release; I Spy (1965-68) with Robert Culp and Bill Cosby; and the comic Get Smart (1965-70) with Don Adams and written by Mel Brooks and Buck Henry.

Thirty years after its seven seasons on CBS, Mission: Impossible (1966-73) became a movie franchise starring Tom Cruise (1996-2011), racking up four box office hits so far. More recently, three features (2002-07) starring Matt Damon based on Robert Ludlum’s Jason Bourne novels have come out. In 2012, The Bourne Legacy, a fourth film in the series, expanded on Ludlum’s themes and characters without Bourne himself making an appearance. On a much lighter note, there is no mistaking the Bond lineage in Mike Myers’ three Austin Powers movies (1997-2002).

The first real franchise of the current movie industry establishment, the James Bond series under the Eon banner exemplifies the outcome sought after by producers. Based on one novel of a popular series, Dr. No’s success easily led to more Bond films drawn from the other books and, later, from original scripts. Another long-running series emerging around the same time, though, demonstrates another path to creating a franchise — when a movie’s overwhelming success demands an unintended sequel. The central figure of this other series must also be attributed to the Bond influence — the ultimate comic “un-Bond” convinced of his own mastery of athletic skills, intellectual prowess and sexual charm — the woefully inept Inspector Jacques Clouseau.

Conceived by writer/director Blake Edwards and made flesh by Peter Sellers in The Pink Panther (1963), Clouseau’s popularity sparked an immediate sequel, A Shot in the Dark (1964). Sellers went on to portray the French detective in five more movies directed by Edwards, ending in 1982 with Trail of the Pink Panther, patched together with unused footage from the earlier films after Sellers died in 1980. Trail was not a success, nor were Edwards’ last two attempts to keep the character alive in Curse of the Pink Panther (1983) and Son of the Pink Panther (1993), with the very Italian Roberto Benigni as Jacques, Jr. Alan Arkin also played the detective in a non-Edwards 1968 Inspector Clouseau, and the character was officially rebooted in the person of Steve Martin in The Pink Panther (2006) and The Pink Panther 2 (2009).

Warner Bros./Photofest

Similarly, the success of Norman Jewison’s In the Heat of the Night (1967), starring Sidney Poitier as Philadelphia police detective Virgil Tibbs caught up in a Mississippi-based mystery, triggered two Tibbs movies (1970 and 1971) set on his home turf, as well as other series with black detectives, including Shaft with Richard Roundtree in 1970 and its two sequels in 1973. They preceded the introduction of Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry, who appeared in five movies between 1971 and 1988, and the three Beverly Hills Cop movies (1984-94) with Eddie Murphy’s inner-city Detroit cop in unfamiliar territory. These foreshadowed Mel Gibson and Danny Glover’s interracial teaming in four Lethal Weapon movies between 1987 and 1998.

During the ’70s, other genre successes became series: the interweaving soap opera stories of the Airport movies (1970-79), the first based on Arthur Hailey’s novel; and the comic sentimentality revolving around the grumpy baseball coach and misfit kids of The Bad News Bears movies (1976-78).

Then in 1975, Steven Spielberg’s Jaws was released wide to theatres throughout the country. Its record-setting box-office success completely redefined studio distribution to hinge on opening weekend returns. The blockbuster had arrived and, as a result, transformed the franchise development process.

Jaws generated three sequels between 1978 and 1987, but every year since the 1975 original seemed to produce at least one huge hit that generated a new franchise. In 1976, Rocky, Sylvester Stallone’s nobody of a boxer who became somebody, led to five more installments between 1979 and 2006. It also led to Stallone’s second franchise, a four-part series (1982-2008) starting with First Blood, about Rambo, the Vietnam vet who couldn’t stop fighting.

Paramount Pictures/Photofest

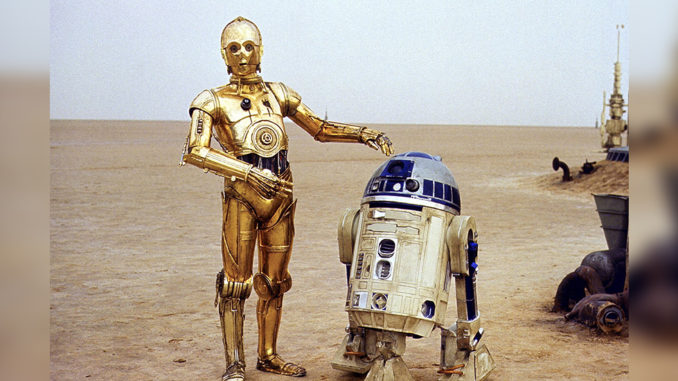

The release of another blockbuster-defining phenomenon in 1977 significantly enlarged the potential profits for a franchise beyond the movie theatre to marketing toys, games, books and memorabilia: George Lucas’ Star Wars. Influenced by Joseph Campbell’s studies of myth, the first three Star Wars movies (1977-83) were actually the middle three episodes of Lucas’ nine-part intergalactic epic. The opening trilogy of the tale was produced much later and hit the theatres as three more movies between 1999 and 2003.

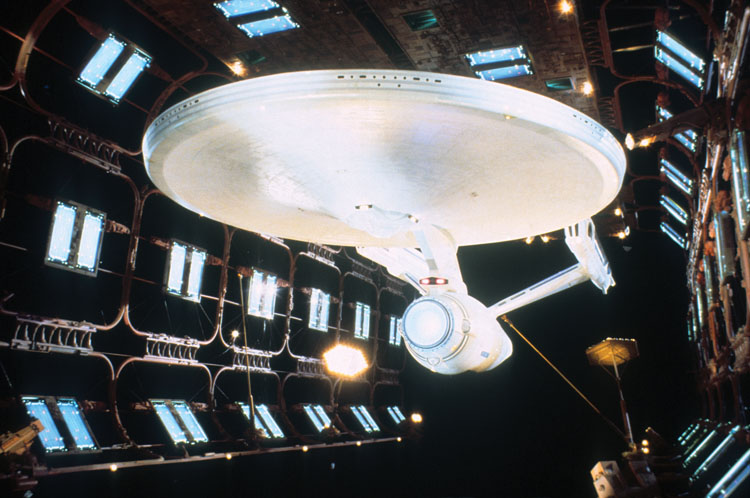

TV’s Star Trek only ran from 1966 to 1969, but the success of Star Wars hastened its revival as a theatrical feature starring the original cast. Directed by veteran Oscar winner Robert Wise, Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979) was followed by five sequels (1982-91) and another TV series — Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-94) — which in turn begat four movies of its own (1994-2002). Going back to the original’s characters, producer-director J.J. Abrams has rebooted the franchise in two films released in 2009 and 2013.

Between the births of the Star Wars and Star Trek franchises, another big-budget quasi-science fantasy genre was born. For years the staple of comic books, low-budget serials and TV shows, costumed superheroes have swarmed onto movie screens since Christopher Reeve first donned cape and tights in 1978’s Superman: The Movie. Three more Reeve Superman movies (1980-87) led the pack until Tim Burton’s Batman (1989) generated three sequels (1992-97). Two reboots of Superman have been attempted (2006 and 2013) and Christopher Nolan has directed Christian Bale in three recent Batman films (2005-12), but a flood of superheroes have hit the theatres this century: three Spider-Man movies (2002-07) and a 2012 reboot, six X-Men films (2000-13), three movies about Iron Man (2008-13) and, now, two Thor films (2011-13). The three Transformers movies (2007-11) belong to this genre as well.

The sheer numbers of multi-film series boggles the critical mind when the lines of descent are laid out for the various movie genres. The post-apocalyptic and dystopian futures in George Miller’s three Mad Max films (1979-85) from Australia and in the four Alien movies (1979-97) are carried on in the four Terminator films (1984-2009), three RoboCop pictures (1987-93), three Jurassic Park films (1993-2001), three Men in Black movies (1997-2012) and three Matrix films (1999-2003). Robert Zemeckis’ three-part Back to the Future (1985-1990) also fits here.

MGM/Photofest

Pioneering another genre, John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) brought about long strings of slasher horror franchises. Seven Halloween sequels (1980) were followed by two Rob Zombie-directed reboots (2007, 2009), and the last of 11 bloody Friday the 13th movies (1980-2009) culminated with one subtitled Freddy vs. Jason in which Halloween’s murderous Jason is matched against Freddy Kreuger from Wes Craven’s seven Nightmare on Elm Street films (1984-1994). Craven also created three Scream pictures (1996-2000), which inspired Keenan Ivory Wayans to make the five Scary Movie parodies (2000-06). As slasher fans have grown more inured to the standards of the form, the grisliest gore has appeared most recently in the seven sadistic Saw films (2004-10).

The screen adventure hero goes back to the movie serials of the 1930s that also inspired Star Wars creator Lucas to invent archaeologist Indiana Jones for fellow serial fan Spielberg to direct four movies about (1981-2008). In Indy’s wake have come two Lara Croft: Tomb Raider movies (2001-03), two National Treasure films (2004-07) with Nicolas Cage and, in a lighter vein, two Night at the Museum pictures (2006-09) with Ben Stiller. The four Pirates of the Caribbean films (2003-11) provide similar action in a more fantastical setting. For modern action pared down to the essentially visceral element of speed, however, there are the six Fast and Furious car movies (2001-13), which may have been influenced by the three Smokey and the Bandit films (1977-83) and which certainly inspired the three French Transporter films (2002-2008) with Jason Statham.

Apart from the British Carry on… series and the Inspector Clouseau franchise, most comedy series have relatively short runs but they lend insight into society’s shifting sense of humor. The stoner comedy of Cheech Marin and Tommy Chong survived through seven features between 1978 and 1990 with the pair as leads, while the deadpan non sequiturs of writers Jim Abrahams and David and Jerry Zucker made popular successes of two Airplane movies (1980 and 1982) and three Naked Gun pictures (1988-94). Slapstick between a cute kid and bumbling crooks drew audiences to three Home Alone films (1990-97), written by John Hughes, while matter-of-fact raunchiness may be what has placed the three Hangover franchise movies (2009-13) among the highest-grossing comedies of recent years.

Most franchise series are made up of movies that are self-contained genre stories sharing central characters and background themes and attitudes. Some series, though, are real sagas, involving viewers in the growth of characters and the continuing development of a story that overarches the plots of the separate films. Preceding Lucas’ Star Wars narratives, the success of The Godfather (1972), based on Mario Puzo’s novel, permitted director Francis Ford Coppola to extend the brutal history of the Corleones into a historical saga in The Godfather: Part II (1974) and Part III (1990).

Since 2000, practically all multi-film sagas have been based on literary fantasies requiring the extravagant use of computer-generated images, perhaps distracting both filmmakers and audiences alike from the richer moral themes intended by the original authors. Still, there is a certain charm to observing the real growth of the actors portraying the young sorcerers of the eight Harry Potter films (2001-11) based on J.K. Rowling’s seven novels. The impressive visual achievement of Peter Jackson’s three-part adaptation (2001-03) of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy may be undercut, however, by his inflation of Tolkien’s other Middle-earth novel, The Hobbit, into three separate movies; the first of the three, An Unexpected Journey, was released in 2012. Despite the success of three films produced that were drawn from C.S. Lewis’ Chronicles of Narnia — The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (2005), Prince Caspian (2008), and The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (2010) — further production of Narnia movies is presently in doubt.

New Line Cinema/Photofest

Two best-selling modern novel sagas written for a young audience have also become movie sagas. Stephanie Meyer’s four-part Twilight Saga transforms the undead vampire of traditional folklore from a vicious sexual predator into an attractive romantic partner and has been made into a five-movie series (2008-12). The Hunger Games, the first part of Suzanne Collins’ trilogy of an oppressive society of the future, came out in 2012; the second part, Catching Fire, opens November 2013, while Mockingjay will be released in two parts in 2014 and 2015.

And so the story of the movie series goes on. For over 100 years now, from episode to episode and sequel to sequel, whether serial or series or saga, these entertainments have drawn the interest and attention of vast audiences. These audiences appear to enjoy what they’ve become most familiar with and the industry responds by continuing to manufacture variations of the same. The real story of Sequelization, though, lies not so much in the stories that attract us as in what the stories tell us about ourselves and our culture.