by Peter Tonguette • portraits by Wm. Stetz

Some six years ago, Tony Soprano dined with his wife Carmela and son A.J. for the last time. You remember how it went. As they chatted with each other and snacked on onion rings, the Journey song “Don’t Stop Believin’” blared from the jukebox, while daughter Meadow (soon to join them) endeavored to get the hang of parallel parking. All the while, unsavory types shuffled around the Sopranos’ table, but before any drama could unfold — there was a sudden, surprising cut to black.

Thus endeth the series finale of HBO’s hit series The Sopranos.

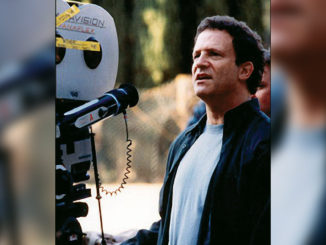

Few edits in memory have caused such a stir, but easily forgotten in the discussion of the scene’s meaning was its gem-like structure: the seamless cross-cutting between inside and outside and the bouncy tempo provided by the song. Until this year, it was the last time editor Sidney Wolinsky, A.C.E., made a cut for writer-director David Chase (creator of The Sopranos). While Wolinsky received an ACE Eddie Award for his work, as he remembers it, much of the moment’s power was present on the page.

“That was the script, essentially — it cut to black,” Wolinsky says. “The challenge of that last scene was to keep the tension up and not let people see that it was coming. The song was chosen before it was shot, as well. David is like a walking encyclopedia of American pop music. He’ll call out the song he wants, but he doesn’t want the studio recording, he wants the concert recording, and he wants this phrase to fall on this piece of picture.”

It is fitting, then, that Chase and Wolinsky’s latest collaboration is Not Fade Away. The film, which Paramount opened in limited release December 21, revolves around Douglas (John Magaro), an adolescent in 1960s New Jersey, who is taken with the era’s musical offerings — particularly the Rolling Stones — and forms his own rock band (as Chase himself did as a teenager). Playing Douglas’ father, The Sopranos’ James Gandolfini is the best-known actor in the cast, which also includes Jack Huston and Will Brill as Douglas’ fellow band mates, and Bella Heathcote as his girlfriend. “I very often get ideas for scripts or for scenes by listening to music,” Chase comments. “Just sitting in the room by myself or with someone and listening on high volume to various songs; it gives me inspiration.”

The idea for Not Fade Away had been in Chase’s mind for a long time, though it took the buzz following the end of The Sopranos for him to be able to make it his debut as a feature filmmaker. “Coming off The Sopranos, I thought I would have a certain amount of capital so that I could use it for getting this movie made,” Chase says. “I knew it would be a difficult one for most studios to approve and to finance because it’s a small, personal story. And it’s not really what’s happening these days.”

It was another music-oriented project — the two-hour pilot for the Chase-produced series Almost Grown (1988-1989) — that first brought Chase and Wolinsky together more than two decades earlier. “It was about a couple who meet in high school,” Wolinsky recalls. “The guy, played by Tim Daly, is a music fanatic. The script was written around songs playing on the radio or at a record store. Then you jump forward to when they’re in college, and he’s a DJ.”

“I forget who recommended Sidney, but somebody did,” Chase says. “I got to know him through that, and I found working with him to be very good for the project. He will not just read the rulebook to you. If you say to him, ‘Let’s put this in there,’ he won’t say, ‘You can’t do that; he’s looking the wrong way.’ I mean, he will say it, but he will try it anyhow. I found that invaluable. He goes at it and goes at it and goes at it.”

Born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Wolinsky’s ambition was not to flout the rules of editing. He graduated from Brandeis University with a degree in English and American Literature, and while he was a self-described film fanatic, he had little sense of how he might translate his enthusiasm into a career. He ended up attending San Francisco State University, where he earned a master’s degree in film. “While I was getting my master’s, I discovered I really liked editing,” he remembers. “What I liked about film was telling the story or being involved in shaping the story. I worked a little as a soundman and as a DP on student films, but all of those seemed extremely technical. There was an excitement in actually taking a film and putting it together.”

One of Wolinsky’s first jobs out of school was working for legendary producer Ross Hunter. Following such big-screen successes as Imitation of Life (1959) and Airport (1970), Hunter made several made-for-television movies, including Suddenly, Love (1978) and The Best Place to Be (1979), on which Wolinsky was an assistant editor. Hunter’s métier was melodrama, a genre he took very seriously. “He used to cry in dailies,” Wolinsky recalls. “The editor, Richard Bracken, and I would sit behind him, and he’d be sort of sobbing during the dailies. He was very serious and loved this stuff.”

Wolinsky’s early encounter with movies of the week presaged the direction of his later career. In addition to series like The Sopranos (1999-2007) and Rome (2005-2007), he edited more than a dozen movies for the small screen, including several with director Alan Metzger. “I did a few big features early on,” Wolinsky notes. He assisted Richard Marks, A.C.E., on the cult classic Pennies from Heaven (1981), and later worked alongside Marks as an additional editor on the hugely successful Terms of Endearment (1983).

Photo by Barry Wetcher. Copyright Paramount Vantage

Even so, Wolinsky made his mark on television (in fact, Not Fade Away is his first feature since 1995). “For various reasons, you take the jobs that you are offered, and I did end up on a lot of movies of the week,” he says, although in hindsight admits that he had enjoy most of his experiences. “They were sort of little movies, and you were on your own with a director,” he adds.

But their subject matter was often pulpy and generic — in short, a far cry from the qualities associated with the writing of someone like Chase. So, when Wolinsky’s agent sent him the script for the pilot of The Sopranos, he wanted to get involved. While Chase selected another editor to cut the pilot, Wolinsky worked on the first episode after the pilot, becoming one of the series’ three main editors, along with Conrad Gonzalez, A.C.E., and William Stich, A.C.E. They worked on episodes on an alternating basis, although frequently there was overlap between episodes, meaning that Wolinsky might be preparing a director’s cut of one episode as he was applying Chase’s notes to another. Though not himself a musician, the editor offers this analogy: “It’s like if you’re a musician. You could be playing a Chopin piano concerto and then put it down and pick up something by Alban Berg and play that. They’re separate sort of things, but you’re using the same skills.”

He adds, “Sometimes David would just set a show aside, and then work on it later. It could take weeks or months — literally months.”

Unusual for a series, Chase was the only producer with whom the editors were in contact after they finished working with the director, so he and Wolinsky developed a rapport, even though they were sometimes separated by thousands of miles. “We edited it via satellite,” Chase says, adding that on occasion he might be in France while Wolinsky was working in Los Angeles. “It was like being in the room. In other words, we were hooked up through a phone line. We could talk to each other — me and all the editors. And then I had a screen, which was presenting what was on the Avid. I could say, ‘Okay, just back it up two or three frames’ or ‘Cut right there.’”

Nevertheless, Chase was glad to be physically present during editing this time. “I just like the social aspects of it,” he says. “Hanging out there, talking, having lunch with the assistants, all that. It’s just a nice place to be. There’s the editing room, and then there’s a music editing room, and then there’s a special effects editing room. And when they’re all close together like that — amazing stuff. You can look in on one thing, and then look in on the other. It’s a great feeling.” From Wolinsky’s perspective, having the director in the building as he finishes a scene, or executes an idea, eliminates the middleman. “Whoever you’re working with has to approve what you’re doing, so the more accessible they are the better, usually,” he says.

“Preparing for musical numbers in a show like Not Fade Away is technically very complicated, Those numbers are shot with multiple cameras to a pre-recorded playback track. On the set, the actors listen to the pre-recorded track played live on the set, and replicate the playing or singing. For this all to work properly, a lot of advance preparation is needed…” – David Massachi, Assistant editor

It may be even more important in Chase’s case since extensive changes in post-production are common for him. “I think editing is just an extension of the writing process for him,” Wolinsky observes. “We would restructure shows. He would rewrite a whole bunch of lines. I’d have to cut around to someone’s back so we could change the second half of a sentence.”

For Chase, the whole point of editing is to find “an electric spark” in combining pieces of film that weren’t necessarily meant to go together. He says, “If you’re writing a script and you want to change something, you can just erase the whole thing, or erase a part of it, and write something completely new. With editing, you really can’t do that unless you re-shoot, and re-shooting is expensive, as we all know. So you have the elements that are already there, that you shot, and then you try them in various configurations.”

On Not Fade Away, an entire voiceover narration was added during the editing. Instead of being in the words of the protagonist, however, the voice is that of his young sister Evy (Meg Guzulescu), a supporting character. Wolinsky explains, “She’s not a leading character, but she’s there. I think David felt she was a witness to the times.”

About the voiceover, Chase offers, “Probably it’s always been in my head since I read Wuthering Heights, which is not narrated by Heathcliff or Cathy. It’s narrated by the housekeeper. That’s what’s so great about editing. You’re not finished shooting the movie at all. You’re still making it. You’re still creating it.”

In making the film’s amateur band look and sound credible, Wolinsky relied on music editor E. Gedney Webb. “There’s always a tendency to believe that, ‘Oh, no one will notice’; who cares whether the fingers are in the right place on the guitar,” Wolinsky says. “But the first thing Gedney would do is slide the sync on stuff, so that the sync looked perfect. He would come in and say, ‘You know, the fingers aren’t in the right place on the guitar.’ I’d say, ‘Gedney, this shot is so wide, no one will ever know.’ He’d keep hammering away, and finally I’d say, ‘Okay, let’s find a solution,’ and we’d sit down together and I’d shift the track or I’d find another shot or I’d cut off of the person.” The songs themselves were recorded by music supervisor Steve Van Zandt, along with what Wolinsky describes as “virtually the entire E Street Band — minus Bruce Springsteen. The challenge for them was not to sound too good. I’m not joking!”

Wolinsky also depended on his assistant editors, especially first assistant David Massachi and second assistant Dave Rogers. “Preparing for musical numbers in a show like Not Fade Away is technically very complicated,” he says. “Those numbers are shot with multiple cameras to a pre-recorded playback track. On the set, the actors listen to the pre-recorded track played live on the set, and replicate the playing or singing. Back in the cutting room, the playback track is synced to the production track and picture, and I ultimately only use the playback track. For this all to work properly, a lot of advance preparation is needed, and when the dailies come in, more work is involved in preparing the material before cutting can occur. This is only a small part of the support work done by the assistants.”

It is unlikely that there is any cut in Not Fade Away that will provoke the same level of comment as the one that ended The Sopranos, but its spirit of experimentation remains. Explaining why he and Wolinsky get along so well in the cutting room, Chase offers, “We both like to fool with the footage and see what happens.”