By Michael Goldman

At Skywalker Sound, women are making connections – and that makes all the difference.

Danielle Dupre, a re-recording mixer and eight-year veteran at the famed Northern California facility, says she got her foot in the door thanks to the grace of another woman industry professional she had long admired.

“I emailed Leslie Ann Jones, now director of music recording and scoring at Skywalker [as well as a recording engineer and mixer], with no previous introduction,” Dupre recalled. “She got back to me right away and invited me to [Skywalker Ranch] to have lunch and meet some people. That’s how I met the guy who later ended up hiring me for an entry-level position that no longer exists-recordist. Leslie was so nice and made it obvious she wanted to help another woman in this industry.”

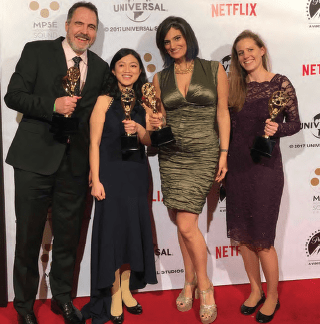

Bonnie Wild has also been at Skywalker for eight years, winning two Emmys as a re-recording mixer and sound effects editor. After having worked in the audio industry in her native U.K., Wild’s contacts got her a tour at Fox Studios during a vacation, and on that visit, she felt inspired by seeing industry veteran Anna Behlmer using a digital film console while working as re-recording mixer on “Kung Fu Panda.”

“I looked at Anna doing her pre-dub pass on that film and I thought, this is what I want to do,” Wild said. “I got trained on a DFC in England where I worked, and then moved to America specifically to try to get to Skywalker Sound. I was eventually offered a job in digital editorial services, an engineering role, and started there.”

Those are just two examples of prominent women audio professionals who were inspired or guided by those who came before them over the years.

Today, the company believes that building diverse crews makes both good sense and is creatively beneficial, according to VP and general manager, Josh Lowden. “Ideally, we want all the people involved in telling stories to be speaking from their own experience and bringing different perspectives,” Lowden explained. “But more diversity also enables our teams to solve problems in unique ways. By growing diversity in our teams, we ensure that they come with different perspectives and solutions.”

Thus, Skywalker Sound is a facility where some of the audio industry’s longest-tenured and most highly decorated women are headquartered-where Jones (five Grammys and eight nominations); re-recording mixer Lora Hirschberg (a 29-year Skywalker veteran and the first woman to share an Oscar for achievement in sound mixing for “Inception” in 2011, one of two Oscar nominations in her career); and others have achieved major industry distinction; where internship and apprenticeship programs are actively seeking women and other groups to enhance diversity; and where the audio work on “Mulan” (2020) was handled by what that film’s sound designer, Krysten Mate, called “the most female-heavy post-production show I have ever been on. I went from sometimes being the only woman on a stage earlier in my career to working with a sea of women.”

In other words, over the years, Skywalker Sound has become a place where, as Wild put it, “a roomful of guys is not perceived as a normal thing anymore.”

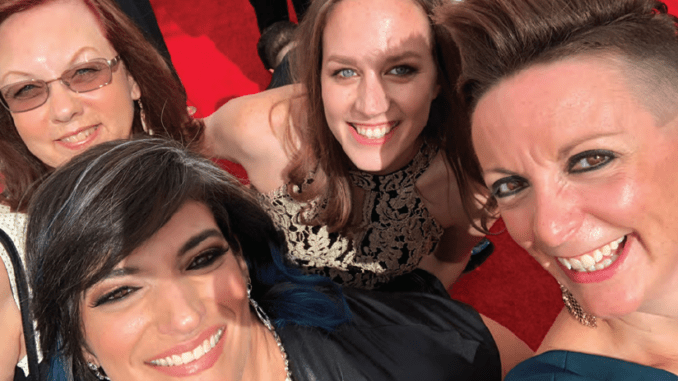

How this came about is due to a convergence of factors that the 10 women surveyed by CineMontage point to-including an active camaraderie shown by an informal “sisterhood” at the facility, as Wild refers to Skywalker’s close-knit team of women professionals.

‘Priceless Guidance’

Kim Patrick, now a supervising sound editor, sound designer, and re-recording mixer started at Skywalker in 2012 in the company’s internship program under sound designer Randy Thom and re-recording mixer Leff Lefferts, and was then asked to apprentice for supervising sound editor Gwen Whittle right out of her internship. Just ahead of her in Skywalker’s internship program was current supervising sound editor Baihui Yang, who also interned for Thom before he guided her into an apprenticeship and the world of assistant sound editing. In both cases, the two women took advantage of formal entry programs, but once they got inside Skywalker, they found themselves receiving priceless guidance from experts.

“Toward the end of my internship, Randy offered me an apprenticeship position on a sci-fi movie,” Yang said. “Through that, I was able to join the union. And from there, I worked as an apprentice, then assistant editor on a few movies, learning editorial skills. This was a very intense yet exciting program. Since my desk was only six feet away from Randy’s, I was immersed with his sound design work all day long.”

In the area of apprenticeships, Lowden says Skywalker has diligently tried to build a fertile training ground for young talent as a way to increase diversity, in addition to the company’s ongoing efforts to improve balance and representation in other ways.

“[Smaller crew sizes] have made it harder for new people to get into the industry and get the experience they need,” he said. “To help offset this, we’re bringing in new apprentices that are not attached to specific project budgets, so that we can offer them a continuity of experience and training without having to stop-and-start on projects. Along with that, we are pairing up some of our more experienced editors with veteran supervisors to act as mentors.”

For veteran Skywalker women, however, mentoring younger women is more than a formal program-it’s a passion. Whittle, now a supervising sound editor and a two-time Oscar nominee, is among a group of trailblazing women on the company staff who, in addition to their professional duties, are actively looking to open doors for younger female professionals. She’s been at Skywalker 32 years-“as long as the building has been operational,” she says proudly-and worked on the second film ever to mix at the facility, “Willow” (1988), as an assistant sound effects editor.

She well remembers often being “the only woman in the mix room,” but since that era, she says, the art of mentoring has been among her favorite pursuits.

“The Ranch has always been good at incubating talent,” Whittle said. “But anyone who has ever worked with me as an assistant knows that if they have any interest in dialogue and ADR editing, and many certainly do, I will be happy to teach them everything that I do.”

“The Ranch has always been good at incubating talent,” Whittle said. “But anyone who has ever worked with me as an assistant knows that if they have any interest in dialogue and ADR editing, and many certainly do, I will be happy to teach them everything that I do.”

Patrick seconds the notion, declaring, “the mentorships I have received over the course of my education and career thus far are something I consider to be absolutely essential for my own success and progression. Now, I’m hoping to do the same, especially for women still in school or just starting their careers.”

She points to resources many Skywalker women support, like the Women’s Audio Mission (WAM), a San Francis-co-based non-profit that Patrick calls “a leader in training women for audio-related careers and connecting women audio professionals from around the world. This model of training and connecting women in the field really resonates with me and seems like one of the best ways to maintain a large and active sound community.”

‘A roomful of guys is not perceived as a normal thing anymore

Melanie Mociun, currently an audio technician at Skywalker who has been at the facility since 1986, emphasizes this point – the desire of established women of Skywalker Sound to help a new generation of women audio professionals extends beyond facility work. She praises her colleagues for actively participating in and encouraging external outreach programs. For example, Hirschberg and Dupre donate time to Reel Stories, a non-profit youth media organization to guide young women in making content and pursuing media careers, and Jones has taught recording at the Institute of Musical Arts in Massachusetts and at that program’s summer camp designed for girls and young women.

Dupre adds “it was no coincidence” that she reached out to Jones when she first circled Skywalker Sound, saying, “I felt my chances of being seen and taken seriously were increased by approaching another woman.” When she eventually got hired, Dupre emphasizes that Hirschberg, though they did not personally know one another at the time, quickly “sought me out within my first few weeks. She came into the machine room at lunch, introduced herself, and immediately [invited her to lunch]. I came in with a lot of ‘imposter syndrome,’ wondering if I fit into the roles that interested me. But just getting to know Lora, and knowing that people like her exist in the building gave me a lot of confidence trying to jump-start my career.”

The Incredible Shrinking Crews

During the film era, early in her own career, Mociun emphasizes that audio crews were much larger than today. She also points out that Skywalker Sound has had three woman general managers over the years and has always had women represented in its workforce. However, she says, for some reason, jobs like re-recording mixer and sound effects were typically male-dominated. Whittle agrees, saying “back in the film days, I’d say it was pretty even on [Skywalker film crews], male and female. But even then, there were not many female mixers. Lora Hirschberg broke through in that area for us [as a Skywalker employee].”

And Krysten Mate remembers that while “there were quite a few women working in sound post-production in Northern California” generally when her career launched in the 1990s, “most of them were doing dialogue and ADR or were Foley walkers. Very few were in sound design, sound effects, supervising, or mixing.”

Then, as the digital era took hold across the industry, crews started to shrink. And with that fundamental shift, Dupre suggests that for a time, “although men and women both had technical computer skills and should have been hired equally [for new computer-oriented jobs], stigmas unfairly kept women from being seen as qualified.

“With people on the margins, when there are natural shifts in the industry, they are often the first ones to lose opportunities, and I think that happened to women in this industry for a time after we went all-digital,” Dupre said. “I think there was a stigma, even on the part of some women, that when it came to technical stuff, it was somehow out of our grasp. That is completely not true, of course, but when we went all digital, that stigma and the fact that there were less jobs hurt chances for a lot of people.”

Still, Skywalker Sound has always been more progressive than many facilities, the women suggest, and over time, headway was made in that area. Indeed, Mociun helped research an October 2016 article for the IATSE Connection newsletter put out by IATSE’s Women’s Committee, and during that work, she and author Barbara McBane concluded that by 2016, “Skywalker Sound probably employed a larger percentage of women at all levels of sound post-production than any other major facility.”

Furthermore, in more recent years, a path into the facility through technical or engineering work has become increasingly feasible for women. Plus, the availability of globally accredited courses (such as ECDL) makes it easier for women to pursue them and gain the necessary skills to find a way into the industry for technical work. One reason is that for creative positions, Skywalker typically selects from within, promoting liberally and following the apprenticeship and mentorship training models previously discussed. Most creative talent there are fulltime independent contractors, so, they suggest, basically getting into the facility to begin with can be the hardest part. But once there, excelling, showing initiative, and taking advantage of the rich mentoring culture to learn skills has proven to be a productive path for reaching creative positions.

For instance, though Wild had creative experience in her native UK, she is glad she initially landed on the technical side of the company before moving into mixing and editing.

“What is great about working on the technical side is the amount of stuff you get to learn,” she said. “You learn everything about the equipment, which is great for when you become a mixer, because you really have to know that console. You are also in the room watching [others] mix, how they interact with clients, deal with politics on stage, and see mistakes get made and how they get resolved. So I’m a firm believer in taking the engineering path.”

Another key industry paradigm shift that has created new opportunities involves the rise of streaming content direct to consumer homes-a shift that, at this point, has evolved into an area “that is just exploding,” in Hirschberg’s words. Now more than ever, there is a rabid demand for content of all types and genres, and therefore, as Wild puts it, “there are a lot more jobs kicking around, at this point.”

“[Streaming] is expanding the workforce once again, which is good for women,” Whittle emphasized.

The women also credit the Guild for helping to even the playing field, particularly where historic obstacles like comparable wages, childcare, and healthcare are concerned. “It’s expensive to live in California,” said Whittle. “We want to give young women enough work and training to keep them inspired as they learn the industry, but they need a living wage to do that. The union has been important in that regard.”

For young women entering the industry, getting into the union is both a great motivational factor and a practical layer of protection that makes learning the industry a feasible endeavor. All of which is probably why women have historically been quite active in Guild service at Skywalker. For instance, re-recording mixer Elizabeth Marston is the latest of several women to serve there as shop steward. During negotiations a couple years ago, Marston was key in helping to create a new rate and rank for the position she held at the time at Skywalker, assistant re-recording mixer. Today, she said, “I find great value in my role as shop steward.”

“Basically, we need to make sure these young women are successful economically, that they can afford to come in and learn how to do this,” added Hirschberg. “That’s one key benefit of a labor union-giving workers the financial stability to build their careers and take care of their families.”

Breaking the Glass Ceiling

All of this is not to say that Skywalker, or anyone else, has achieved true gender parity. That’s why the Skywalker women have suggestions for how the industry at large could push this transition into the next phase and beyond. Among those suggestions is the notion of working to eliminate “unconscious bias,” as Mate puts it.

“Skywalker makes a conscious effort to pull more women into roles that will break the glass ceiling of the supervisory and top creative positions,” Mate says. “But [around the industry], I don’t know that ‘boy’s club’ is the right term anymore. I find it is now a far subtler and possibly unconscious bias, but it can nevertheless have detrimental effects on women’s careers. In a freelance, creative business like this one, you are often at the whim of whether someone ‘feels’ you are a good fit or not. If that person is a male who has not worked with a lot of women, it is likely he will pretty much always pick another male. My solution is to put a lot more qualified women in front of them-widen the field of candidates.”

Dupre, meanwhile, argues that good intentions are not sufficient-“companies need to have plans of action.”

“We have to move from thinking we have checked off the ‘diversity box’ to thinking about how diversity will make the content more valuable and be the best way forward for the company,” Dupre said. “Companies should put diversity at the forefront of hiring practices, and you need to make sure that those people can learn, be mentored, and be given the tools to succeed.”

Hirschberg urges the industry to do a better job actively reaching out to inspire young women.

“It’s incredibly important for young women to see us and be able to imagine themselves in these jobs,” she said. “Women must not self-select out of applying for positions or careers because they don’t think they would ‘belong.’ Employers must work harder to [encourage women to apply and assure them] that they will be seen, included, and considered. That means changing how we search for candidates and how we have them apply for jobs.”

If companies want a better understanding of how to achieve such goals, Marston suggests the obvious: ask women.

“If you want to make positive changes that benefit women, you should ask women what those should be,” she said.

“There are changes that can better suit women in this industry, like better maternity leave policies that increase job retention and placing more women in administration and decision-making positions to make policy changes possible. The women representation gap is one thing that has to improve.”

Leslie Ann Jones points out that women need to have confidence in the fact that they have every right to any industry opportunities their talent and hard work can bring them, and they should be eager to bring their own unique perspectives to the table.

“I learned long ago that gender is important,” said Jones. “As much as we’d all like to be treated the same (and we should), as women, we have our own perspectives on things. It’s important to bring that to the table. Our gender is important, as is the diversity we bring.” And besides, she adds, from a creative and business point of view, “better choices are made when there are more voices and perspectives in the room.”

In a sense, that is the ultimate argument when discussing why it matters if crews and projects are gender-balanced or not.

“There are only two things a person brings to a work team,” said Yang. “Their professional skills and their personal experiences.

The skills are the foundation, but the personal experiences are what can elevate movies, a form of storytelling, to a different level. Our product will be received by global audiences in today’s age, so a creative team that better reflects the components of our audiences will naturally make for a better received product.”