by Stephen Semel, A.C.E.

In November of 1963 I was a 12-year-old, New York Times-reading, politically aware, four-eyed, chubby bookworm. I was in my seventh grade art class, my last class of the day, when the news came over the school’s PA that President Kennedy had been shot. As I rode home on the school bus, I remember my fear that Kennedy’s death would increase the election chances of Senator Barry Goldwater, the Republican front-runner for president, who had stated his willingness to use nuclear weapons pre-emptively against our Communist enemies.

I watched a whole lot of TV when I was a kid. In January of ‘64, in the midst of the gloom cast by Kennedy’s assassination, That Was the Week That Was, the first televised American half-hour political satire, premiered on NBC. Some of the great comic minds of the time were on TW3 every week, ridiculing our national political leaders. There was certainly plenty to satirize: the unbending militarism of the Right, the pro-segregation political establishments of the South and the North, the Johnson Administration’s specious logic behind our undeclared and widening war in Vietnam. Thus began my education in distrust and contempt for authority––an education deepened by Stanley Kubrick’s brilliant take on the men responsible for the defense of the United States.

In the spring of ’64 I had seen Pablo Ferro’s TV spots for Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. The ads featured flashed images from the film inter-cut to a countdown from ten to zero, simulating the effect of the countdown preceding a military test explosion. At zero, the ad cut to stock footage of a hydrogen bomb’s mushroom cloud. The film was promoted as a comedy about nuclear annihilation, an absolutely singular proposition at the height of the Cold War. I was fresh from my “duck and cover” drills in school, in which we were told that we’d be safe from the effects of a nuclear explosion if we hid under our school desks (we knew it was nonsense).

The War Room, the fictitious set in the basement of the White House, with its enormous circular table for generals and politicians, and its projected world map of the locations of the US Nuclear Force, was mesmerizing at that size.

Dr. Strangelove’s appeal to me was the prospect of laughing at all of the shrill militaristic nutjobs that I feared would come to power if Goldwater were elected president. They believed that deposing the governments of the Soviet Union and Communist China, by any means, including nuclear weapons, was a holy calling. They would start a nuclear war, and then the world would end. Or so I feared.

One Saturday, my dad and I saw Dr. Strangelove at our local drive-in. Usually packed on the weekend, it was nearly empty that evening. I guess a black comedy about nuclear war wasn’t a big draw for your average suburban drive-in patron.

Dr. Strangelove was a confirmation of my growing belief about adults in positions of authority. Many of the central characters in the film are ruled by their own unchecked and unexamined lust for power, to the detriment of everyone else on the planet.

The B-52 Squadron sent to nuke the USSR is commanded by General Jack D. Ripper (a chilling performance by Sterling Hayden), who believes that his sexual impotence has been caused by a Soviet plot to fluoridate our drinking water, and who is willing to launch a nuclear war as an act of vengeance.

Dr. Strangelove’s appeal to me was the prospect of laughing at all of the shrill militaristic nutjobs that I feared would come to power if Goldwater were elected president.

The Air Force General responsible for reporting Ripper’s scheme to the president, General Buck Turgidsen (George C. Scott), proposes a full-scale surprise nuclear assault on the USSR, in order to catch them with their pants down. The US casualties, according to Turgidsen? Twenty million, tops.

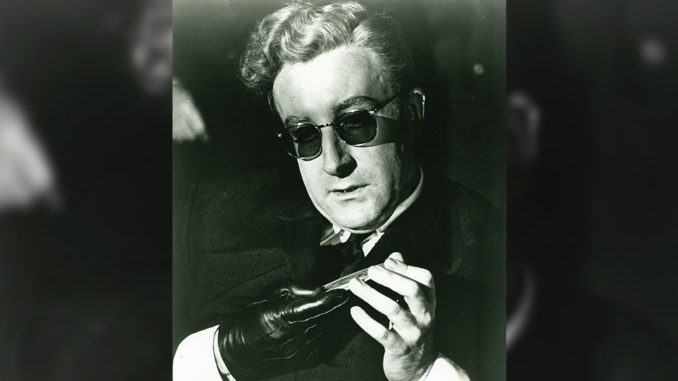

Dr. Strangelove, one of three characters played by Peter Sellers, had been recruited as a weapons advisor from the defeated Nazis. Strangelove shrugs off the impending nuclear winter. His proposal to preserve the human species is to populate a deep mineshaft with a small selection of powerful men and a large assortment of comely young women. After a century-long orgy, the descendants of the survivors would then re-emerge to the Earth’s surface, when the nuclear fallout reached its half-life.

The screen at the drive-in was huge. The War Room, the fictitious set in the basement of the White House, with its enormous circular table for generals and politicians, and its projected world map of the locations of the US Nuclear Force, was mesmerizing at that size. What a contrast between the power of that set and the foolish little bureaucrats who bickered with each other while the planet was destroyed!

The image still serves me well when I listen to the self-congratulatory speeches of public officials, given in inspirational settings––like on aircraft carrier decks. Mission accomplished? Just wait, there’ll be plenty more where that came from.