by Carrie Puchkoff

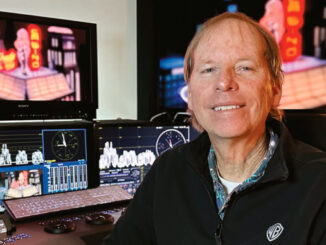

Whether it was kismet or coincidence, my mother could never have anticipated that sitting me in front of an I Love Lucy re-run when I was 17 months old wasn’t just a distraction so she could prepare dinner. Mom rushed in when she heard “screeching,” which turned out to be my chortles of delight at Lucy’s antics. She saw me laughing and quickly realized how to get dinner made for the next ten years. That evening, not only had my mother fostered another dedicated Lucy fan, she also inadvertently guided me along a career path where I would eventually meet the show’s supervising editor, Dann Cahn, ACE.

Every year, Cahn, the innovator of television film editing that all started with I Love Lucy, is a special guest at the Lucy-Desi Days Festival in May and Lucy’s Birthday Celebration in August, both in Jamestown, New York, Lucille Ball’s hometown. This year, what would have been Lucille Ball’s 98th birthday, was particularly special for Cahn. Over 5,000 fans traveled from all over the country and the world for these two events, to watch and listen as he recalled in exacting detail how he structured and shaped the art and craft of television film editing during tribute events in recognition of his industry contributions and in support of the town’s Lucy-Desi Center.

The extent of Cahn’s influence and importance within the post-production community at the time cannot be overstated. In 1951, the studio system was changing and the industry was in flux. Fewer audiences were going to movie theaters and more were staying home to watch the new medium, Television. No one could have imagined then how television would impact the film industry, American culture or the combination of events that would launch the historic and groundbreaking series I Love Lucy.

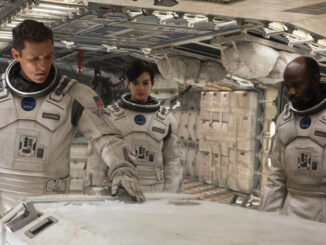

Most television shows were broadcast live from New York City, sometimes recorded onto very poor quality Kinescope to broadcast to the rest of the country. Lucille Ball’s husband and executive producer, Desi Arnaz, had other ideas: He negotiated with CBS for Desilu Productions to pay the difference to shoot the show on 35mm film with an IA Hollywood crew, and in front of a live audience. Filming episodes gave him flexibility and control; he could stay home in Los Angeles with his wife and newborn daughter Lucie, work with familiar crews and production facilities, and add spontaneity to each episode with a live audience.

The producers also wanted to find a young, adaptable, fearless film editor who could take on the unexplored demands of editing on film for the new medium. Since jobs were scarce, a young editor named Dann Cahn jumped at the opportunity to cut the series for the original commitment of 13 weeks. And thus, television culture and its production and post-production standards were forever changed.

I was invited to this year’s Lucy’s Birthday Celebration by Cahn’s son, Danny Cahn, also an editor and, like myself, a member of the Guild’s Board of Directors. In spite of the fact that I continued to really love Lucy, watching re-runs from childhood to this day, I had never been involved in any of the fan festivals or events. Meeting Cahn, senior, and discussing the craft in an historic context would be a rare and momentous occasion. But I didn’t expect that he would offer a perspective of the entertainment industry that would give today’s issues and concerns relevance.

I was introduced to him at the Lucy-Desi Museum on the evening of the first day’s events. He wasted no time indoctrinating me to his oeuvre with a personal guided tour. I asked how the series’ crew came together. “Well, Lucy and Desi wanted the best in the business — the people they had worked with before in film — so they approached those same people,” he said. Was the show required to be under a union contract? “No, but they insisted on working with the best, and those people worked union, so that’s the way it was going to be,” he replied.

Cahn was as passionate about his work as ever. He talked about that first season, his relationships with the producers, with Desi and with his assistant editor, Bud Molin, revealing his dynamic and charismatic persona. I imagined that at the time, he must have offered just the right combination of bold confidence and loyalty for this new kind of cutting room.

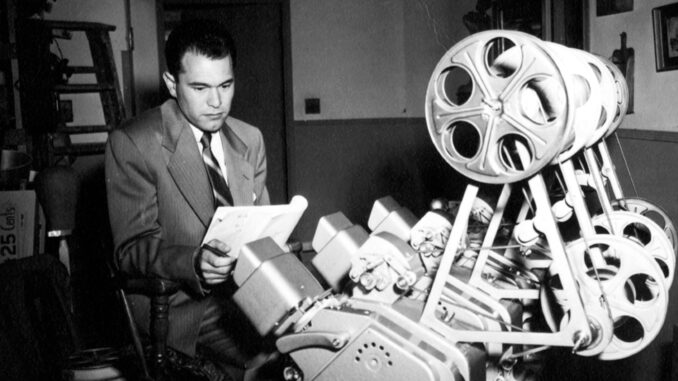

We continued the tour and came upon the infamous “Three-Headed Monster” — a Moviola that played the film from all three camera angles simultaneously and (hopefully) in sync with an optical track for sound. The machine was so dubbed because the prop room was the only space on the stage large enough to accommodate its enormous size. It was daunting for me, a digital-age assistant editor, to imagine the reels of film from three cameras running through it, with the editor marking and making changes, all the while determining and meeting the demands for the new workflow — multi-cam editing in its Beta stage.

Next, I asked him about the optical soundtrack, since I had never worked with one. His eyes widened and he said, “You know, we used to read the optical track with a sort of short hand. We could actually see the sound that had been recorded by reading the levels on the print itself. But when we switched to mag in the second season, we couldn’t read the lines anymore, and it was a lot more work for us. But we adjusted to it and saved a lot of money and time and the quality was much better!”

According to Cahn, the I Love Lucy schedule was tight, especially compared to the more relaxed pace of feature film editing. A new episode had a table read on Monday, rehearsal on Tuesday, camera rehearsal on Wednesday, full camera run-through on Thursday and was filmed, in scripted scene order, on Friday evening in front of a live audience. The film was processed, printed and delivered to the cutting room on Monday morning usually by 8:00 a.m. Cahn marked with a grease pencil, Molin made the cuts (with scissors) and pasted; cut scenes were then adjusted and fixed. The editor’s cut was ready to screen with the director by the time rehearsals for the next episode were already under way. Very quickly, due to demands on set — and with Cahn’s natural ability at cutting comedy and working fast — the director’s cut dissipated. A six-day workweek and 14-hour days was unavoidably established.

In the context of the high-pressure schedule, he recalled, “They thought that the Monster would enable me to do everything, but it was just a tool, like the Avid is today. We couldn’t do everything within the time constraints! It’s expected today that picture editors do temp sound and music work.” The crew quickly increased to include an apprentice and an additional editor for sound effects and music. Cahn remembered Desi Arnaz’s remark to him: “Danny, you want a crew bigger than my band?” And eventually, that’s exactly what happened as Desilu expanded its productions and Cahn’s role in the company.

Inevitably, just as the workload seemed more manageable with Cahn’s expanded crew working on the first episode, it was decided that the second episode would air first. The reaction to the second episode was so strong that the sponsor and the network decided to switch the air dates. The six-day editorial workweek immediately shifted to seven days and, within four weeks, all the editing and sound work, opticals and negative cutting were completed, and the answer print was delivered within hours of airtime. In addition to these unforeseen shake-ups, Cahn also had to think creatively and act fast, especially when things didn’t run as smoothly as planned.

The first serious technical issue the editing team confronted was one still familiar to assistant editors today: fixing out-of-sync dailies. As Cahn tells it, the three-camera setup used a “blue light” system instead of the traditional clapper; as the camera rolled at the start of a scene, all the film rolls were flashed with a light that was exposed onto a frame of film and soundtrack. The three-camera setup was interlocked so that the flash would occur on all three cameras simultaneously. However, the flash from the three different cameras never actually wound up in the same place, as intended, so the task of eye synching most of the footage was added to the crunched schedule.

After the first few shows, Cahn decided to go to the studio mill and have a giant-sized wooden clapper made that would cover all three cameras, and the sync problem was resolved. He recalled DP Karl Freund’s wisecrack to producer Jess Oppenheimer, “We’ve got a bright boy here; with this giant clapper, he’s reinvented the wheel.”

Today, as in 1951, our industry is changing and the future feels uncertain. But if we take a moment once in a while — away from our Avids and ProTools and Final Cut Pros — to remind ourselves how bold, inventive and creative thinking and collaboration defined an era, there is no reason we can’t do it again.