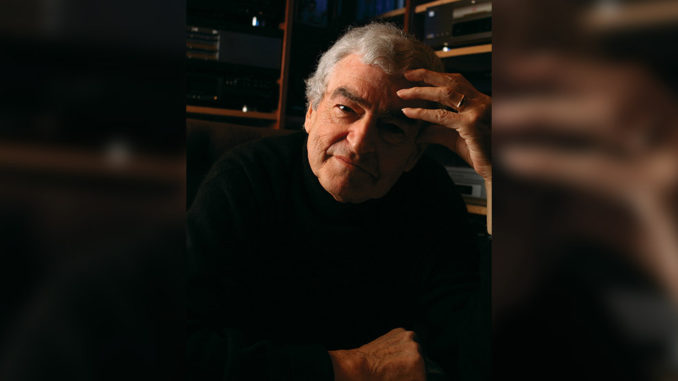

by Kevin Lewis

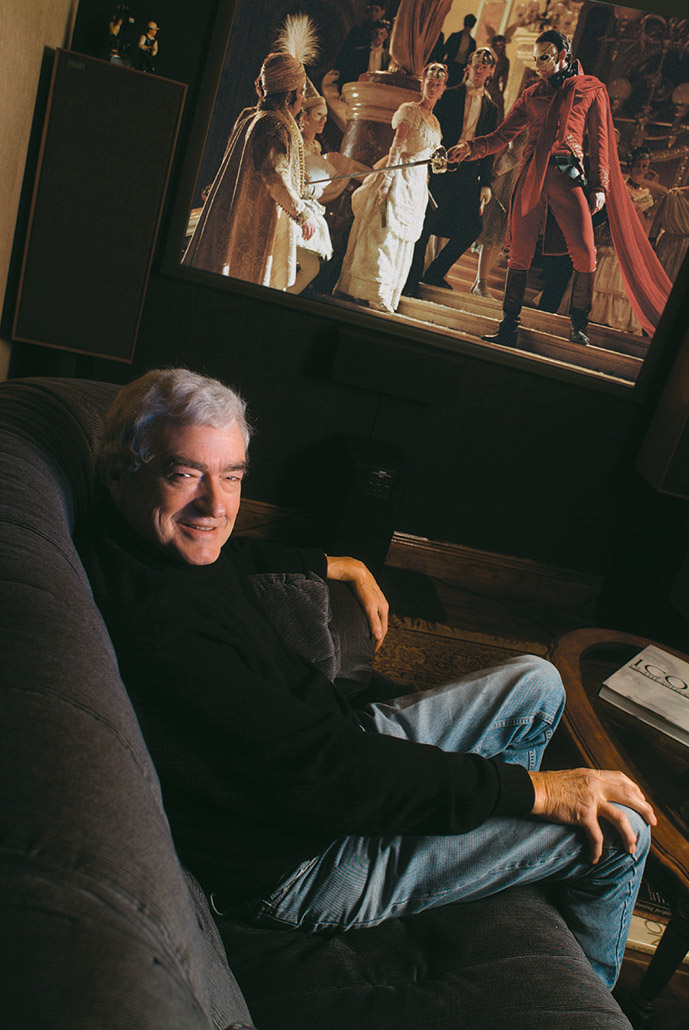

The Phantom of the Opera, the long-awaited film version of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s London and Broadway musical, is one of a few British musicals to be adapted into a musical film. Most British stage musicals––with the exception of Webber’s Evita, his Jesus Christ Superstar collaboration with Tim Rice and Sandy Wilson’s The Boy Friend, which became a 1971 film by Ken Russell––passed into oblivion. The new Phantom may break the curse because of great word-of-mouth buzz even before it was released domestically by Warner Bros. Part of that optimism may rest on the bankable shoulders of Joel Schumacher, a director with many a hit, but Schumacher was wise to hire Terry Rawlings as his editor.

Rawlings has a secure place in film history because he was fortunate to work on some of the significant movies by the spectrum of British directors who created the Renaissance of British film from the mid-1960s through the early 1980s. As sound editor, dubbing editor or music editor, he worked with Russell on Women in Love (1970), The Music Lovers (1971), The Devils (1971) and Tommy (1975); with Karel Reisz on Morgan: A Suitable Case for Treatment (1966), Isadora (1968) and The Gambler (1974) ); and with Jack Clayton on Our Mother’s House (1967). He has worked with Michael Winner as both dubbing editor and picture editor on many films. With Ridley Scott, as first dubbing editor on The Duellists (1977), and later as picture editor of Alien(1979), Blade Runner (1982) and Legend (1985), he helped create perhaps the director’s signature films. Rawlings has appeared in the documentaries on the Alien films and Blade Runner. For Alien, Blade Runner and Chariots of Fire (1981), directed by Hugh Hudson, Rawlings was nominated for Oscars. His editing credits also include Not Without My Daughter(1991), Alien 3 (1992) Goldeneye (1995) and Entrapment (1999).

“I felt released doing a musical. Music has always been a great love of mine anyway” – Terry Rawlings

Rawlings has been a fixture in the film industry since 1957, first as a sound editor and then as a film editor. Although he occasionally works in the United States on films, he has spent most of his life not far from where he was born in London, England in 1933. Before he joined the Motion Picture Editors Guild in 1995, he was a member of the Association of Television and Film Technicians in the United Kingdom. He is also a member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) and American Cinema Editors (ACE). Rawlings, who still loves the movies as much as he did when he was a boy, is proud of his MPEG membership because it means, “I am now an international film editor,” and makes working in America on films a much smoother endeavor.

From his home outside of London in November, Rawlings discussed his career in a telephone conversation with CineMontage. A prime example of an editor who believes he is a storyteller, Rawlings is not a director himself but has absorbed, through close interaction, the principles, which distinguish the directors with whom he has worked.

CineMontage: The new Phantom is a very romantic film, closer to the 1943 version with Claude Rains and Nelson Eddy than the 1925 version with Lon Chaney. Frankly, I expected a different film from Joel Schumacher. Was that intentional?

Terry Rawlings: I don’t know. He never mentioned those thoughts to me, but I just think it’s a film full of heart. It was a labor of love from the beginning. Joel Schumacher is such a professional man to work with. He knew exactly what he wanted to do every day, did it very professionally and didn’t have to work all hours to do it. This helps everybody because they feel confident about what they’re doing. I think he created a great feeling of professionalism around the place. He’s tough, he knows what he wants, and he doesn’t suffer fools lightly, but at the same time, he’s the first to praise as well.

CM: How did you and Joel Schumacher come together on this film?

TR: Paul Hitchcock, one of the executive producers on the picture, was a person I had worked with before. He called me and said he would like me to meet with his director. He told me what the film was so I very excitedly went over there, because it would be nice to do a musical. I had never met Joel before, and we spent half an hour together talking. It was very pleasant. Well, they called me that evening, and said that Joel was very pleased with me and would love me to do the film. And that’s how it happened.

“It took time to get the balance between below stairs and upstairs, so to speak; simultaneous actions are always difficult to create.” – Terry Rawlings

CM: You’ve worked with a wide range of British filmmakers in the 1970s and ‘80s––Karel Reisz, Jack Clayton, Ridley Scott, Michael Winner, Ken Russell and Hugh Hudson. How did you adjust to their various styles?

TR: I find that most of the directors are interesting in their own separate ways. Ken Russell was a very interesting man, but he allowed his editors to do their job for him without too much interference. That happened to me again with Joel. He said, “Go ahead and edit it and do what you will with it. Anything I don’t like, we can work on afterward.” It’s a wonderful way to work because it gives you tremendous confidence in what you’re doing and it gives you a freedom to present your interpretation of the subject, which is very important from an editor’s point of view.

An editor doesn’t just run off and do his own thing. He spends a lot of time––well, I do––talking with the director, getting his thoughts. But I love to be able to work on my own without him over my shoulder. So I give him ideas that he might not have thought of. I think that’s what our job is.

CM: The films you did with Ridley Scott––Alien (1979), Blade Runner (1982) and Legend (1985)––all have a certain romantic elegance to them, though they are about horror and out-of-control future universes. The parallel world in The Phantom of the Opera, between the opera house and the subterranean sewers below, could have approached the horror in the Scott films, but it was romantic. Did you work that out in collaboration with the director? Or did he want that romantic mood?

TR: It wasn’t discussed; it’s a thing that developed as the film went on. I find that the way you work is subconscious. You work on a subject and try to create on the screen the feeling it creates in you.

The interesting thing about films I find is that your first reaction to a sequence is usually the best. When you’ve seen the rushes, you’ve thought about the sequence, you know what the sequence is trying to say, and your first interpretation is usually the best one you come up with. But then you usually have to adapt them because the film is too long, or one thing or another, which is the problem I find.

“Doing a background atmosphere––even if it’s inside a room, the things you might hear drifting into a room––is like painting a picture; painting with sound, brushing in a bit of this, a bit of that.” – Terry Rawlings

CM: The only other musical you did was Yentl (1983). Barbra Streisand was directing a film for the first time, as well as being its star, co-writer and co-producer. Was that one of your most difficult or most satisfying editing collaborations?

TR: Very satisfying collaboration, I loved every minute of it. I mean, she’s a hard taskmaster, but no one goes through a harder time than she does herself. We spent many happy hours going through that film together. She was very unsure because it was her first film as a director, and she was very nervous about whether she was doing everything correctly. It was fascinating, I can tell you.

CM: Phantom has production numbers with a great many people, so you had to conform to the parameters of the musical form. Did you feel hampered by that?

TR: No, in fact, I felt released doing a musical. Music has always been a great love of mine anyway, so being able to work within a musical idiom was fantastic because it sent me on a flow. I would start a sequence and in my own mind it dictated the direction it should go. And that was a great feeling. This film seemed to fall into place for me so easily. As I said, it was a labor of love. I found every day was very magical because I felt that I was really creating something special. I think that it has turned out to be a successful musical, not just a slapped-together stage musical.

People used to say to me, “Oh, you’re making Phantom of the Opera,’ and I said, “Well, actually we are Phantom of the Opera.” You go to the theatre and you sit in the audience and you watch Phantom of the Opera. But you go to the cinema and you become Phantom of the Opera. You get into the whole story in front and behind the stage.

“When I did that picture [Chariots of Fire], I suggested to director Hugh Hudson that we edit the entire film without the Olympic Games in it.” – Terry Rawlings

CM: Phantom did not have the crosscutting editing in the production numbers of say, Chicago (2002), which crosscut and intercut the dance numbers until the dancers became abstractions rather than characters. Yet, it was a character-driven story, just like Phantom.

TR: Well, it was a different subject as well. I think you needed to create that with Chicago. You needed to ‘kick it.’

CM: The opening number, the rehearsal in the opera house that crosscut between the on-stage acting and the mocking stage crew having their tea backstage, was very effective. Was it a satire on the tension of all stage and film sets?

TR: It was to show how the opera house works. It took time to get the balance between below stairs and upstairs, so to speak; simultaneous actions are always difficult to create. What do you show? Which is the most interesting? And you don’t want split screens, because they don’t work.

CM: The carriage ride was very lyrical. Also noteworthy was the sequence where the Phantom spies on the young lovers.

TR: On the roof; that’s marvelous. I just loved him eavesdropping on them all the time. There were a few more cuts of him watching, which I loved, but they were slowly whittled out, unfortunately, in discussions with the producers and Joel. It works though.

“I’ve always had an artistic bent––I like art, I love music––and this led me to what I’m doing today.” – Terry Rawlings

CM: The underground sequences with the ride on the gondola and the myriad of candles are haunting. Was it difficult to edit those shots because of lighting flair? Was there a lot of coverage needed so that you could edit seamlessly?

TR: There was enough coverage to avoid anything that was really blown-out, but we really didn’t have many problems like that. We had a fantastic cinematographer, John Mathieson, who gave us wonderful material to work with.

CM: When you were sound editing with Ken Russell and Karel Reisz, was there anything you learned that you brought to picture editing?

TR: I think being a sound editor for all those years was invaluable to me. It helped me tremendously when it comes to film. I always used to do temp mixes and music for films in those days. I think it gives you an inner rhythm as well. I would listen to music at home that put me into the mood of the subject I was about to cut. I would never cut the film to the music––ever. I wouldn’t put that in until later, but it’s amazing how it gets into your soul.

All this as far as editing is concerned is subconscious. The subconscious mind is working all the time because you learn your trade, and then when you’re doing your job, the thing to do is to forget how to do it. You do it the way it feels to you.

“An editor doesn’t just run off and do his own thing. He spends a lot of time––well, I do––talking with the director, getting his thoughts.” – Terry Rawlings

CM: How do you create atmosphere?

TR: I’ve always been a great lover of creating the right atmosphere for films when I did sound. I used to build my sound from the atmosphere up. Now, they all do dialogue mixes first when they’re doing a final mix. I think you should do your atmosphere mixes first. You create the atmosphere of the “real,” so to speak, and then you can place your dialogue and your sync effects onto that, and they sit in the right perspective. Doing a background atmosphere––even if it’s inside a room, the things you might hear drifting into a room––is like painting a picture; painting with sound, brushing in a bit of this, a bit of that.

When I did Alien (1979), for instance, it was a very hard film to present to anybody because in trying to create the terror, you wanted to take as long as you could to push someone in a room, to push him against the wall. But how long could you hold him there before the audience said, “For Christ’s sake, get on with it!” You had to think about the sound that was going to come, and the sound was equally 50 or even 60 percent of that film; that made it work. [As a picture editor] that was one of the early films in my career, so sound was uppermost in my mind for many years.

CM: Ridley Scott is very attuned to creating moods through sound. Is that why you had such a great collaboration with him?

TR: The last film I did as a sound editor was Ridley’s The Duellists (1977) [which established Scott as a director]. That was a great love to do that film.

Every one of those duels was different, and you wanted each one of them to sound different, so that was an interesting exercise. When he was going to do Alien, his office phoned me up and said they would like me to do the sound on it, and I said, “No thank you; I would like to cut it.” So they invited me over, I met with the producer and the rest is history.

“I just think it’s [The Phantom of the Opera] a film full of heart. It was a labor of love from the beginning.” – Terry Rawlings

CM: In the 1970s, London became a center for sound, animation and editing because it was a great place for experimentation. Were you happy that you had your grounding in England as far as an editor was concerned? Were you able to experiment more?

TR: I think so. I have only done one animated film, which was Watership Down (1978). I had never worked in animation before, but I found it fascinating that you sit down with the animators and director to discuss sequences. And you might say, “Well, for me, this character really is taking too long to get across this field to get to wherever he is going in the film.” And they would say, “Would you like us to move the tree? Would you like the house put a little closer?”

When you do an ordinary film, you have to make it work regardless, but in animation they can just adjust it for you. All the changes that were discussed get developed during that period.

CM: Your editing principles augment the directorial choices and possibilities in storytelling and narrative drive. And you worked with the most innovative British directors. Karel Reisz even wrote the textbook on film editing [The Techniques of Film Editing]. What did you learn from them?

TR: Karel Reisz taught me the meaning of words, which was fascinating. Before I did an actual film with him, I did dialogue for his Morgan: A Suitable Case for Treatment (1966). The hours I spent with him, and his patience going through all the different dialogues we had––and looping and wild tracks––to form a performance was such an insight into what words mean. It’s a thing you never forget, and it’s wonderful when you are searching for a performance. And the same with Jack Clayton. He taught me what performance meant, and working closely with him was another tremendous education.

“Being able to work within a musical idiom was fantastic because it sent me on a flow. I would start a sequence and in my own mind it dictated the direction it should go.” – Terry Rawlings

CM: You must have studied painting because you have an excellent sense of detail and subtle touches, and you mentioned sound design as akin to painting.

TR: I can honestly tell you that I didn’t have painting courses [chuckles]. I just had what we call over here a secondary modern education; nothing special.

But I’ve always had an artistic bent––I like art, I love music––and this led me to what I’m doing today. I think it’s looking at other work, looking at other films.

I am an avid collector of films, and I watch films practically every day. When I’m not working, I’m watching something else; when I am working, I don’t watch anything. I analyze films. All the things that you like and appreciate and admire get filed in the back of your head for use, and they all become part of you.

That’s what makes you into this particular person.

Give four editors the same dailies to edit, and we’ll all show you a different film. We’re all working with the same material but we all feel differently about it. This is what makes this job so exciting because we all put our own slant on something.

“The last film I did as a sound editor was Ridley Scott’s The Duellists. Every one of those duels was different, and you wanted each one of them to sound different.” – Terry Rawlings

CM: Chariots of Fire (1981) transformed sports films and thinking about the past in movies. The Olympic running sequence, with the music score by Vangelis, was copied many times in succeeding years.

TR: When I did that picture, I suggested to director Hugh Hudson that we edit the entire film without the Olympic Games in it, so that when we came to editing the sports events in the Games, we would know how these characters would react to one another. This worked out extremely well because by the end of putting the whole thing together, we knew who the friends were, and who didn’t get on.

Looking at all this material, I thought to myself, “Well what can we do to give it something more interesting than just the race?” Because it hadn’t been long since we had the Olympic film Visions of Eight (1973). I suddenly thought to myself, “Why don’t we turn some of this into a ballet?” Because it’s so lyrical, so beautiful to watch, with good athletes doing their thing… That’s what worked so well for the film.

Editing it, I felt halfway through like I felt about Phantom: This really feels good. Everything seems to be right with it. I knew they would love it in England and Europe, but I never thought they’d like it in America. [It was a big hit in the US and won the Academy Award for Best Picture.] It suddenly dawned on me: It’s about endeavor and you Americans love endeavor. If you work hard enough, you can succeed, and I think that’s what did it for that film as far as the Americans were concerned.

“The subconscious mind is working all the time because you learn your trade, and then you forget how to do it. You do it the way it feels to you.” – Terry Rawlings

CM: The runners appear to be floating because of the Vangelis theme and the image and music are so inseparable in one’s memory that they seem to have been conceived together. Was Chariots cut to the theme?

TR: No, it definitely wasn’t, because Vangelis didn’t have this opening title theme––the one that became world-famous––composed at the time. He came up with this theme about two days before we did the final mix. We were using a piece from an album––I can’t recall what it was now after all of these years––in case he didn’t quite come up with a theme. It was very similar in style, so it would have worked. But the film was never cut to that magical theme.

CM: Do you edit on an Avid?

TR: No, I am a LightWorks Touch person.

CM: What computer do you use?

TR: My God, you’d have to talk to my engineer, [assistant editor] Tony Tromp [Trompetto] about that, because I just drive it. I can’t fix my car but I can drive it all right.

CM: Do you like working with the new technology?

TR: Yes, I do. I like the fact that it’s quick and you can analyze everything very quickly. If you get an idea, as outlandish as it may seem, you can try it. You can do tricks with dissolves and see if a certain dissolve will work. All these sort of things I like about it. Lightworks Touch is very similar in its handling to an old Steenbeck. Their controls are virtually the same, which gives you a great feeling of the past [laughs].

Lightworks has a fantastic memory. Tony said to me when we’d finished the film that we’d only used half of its capacity! I love the tactile feel of working with film and I have done it all my life, so it’s very hard to bend me in that technological direction, but I’m glad I went that way now because I just love the facility of being able to remember all the ideas I’ve ever had. But what it also has––particularly for a director––is built-in indecision, because there is nothing it will forget.

CM: How many assistants do you work with?

TR: I have two wonderful people working with me: Tim Grover, whose been with me for 17 years, is my assistant, and Tony Tromp, who is my engineer as far as the Lightworks is concerned. They are brilliant. They look after everything for me, and allow me to just edit.

CM: What is your favorite sequence that you edited?

TR: The sequence I have always loved, always, is from Yentl––the wedding. Remember the wedding? It was intercut with the preparations. That was something I liked very much. Phantom, overall, I thought was great. I love the masquerade ball; there are so many things about the film that I love.

CM: Were the musical numbers post-dubbed in Phantom?

TR: Some were. Some of the orchestration was redone. They shot everything to playback, obviously, but in a few cases they re-recorded the vocals where they wanted to improve things, so it was really an ongoing process. Once I had the sequence cut, they could take it and do some more work on it.

CM: So, you didn’t have to re-cut the film?

TR: No. I would say there were about five cuts or trims, or adjustments to cuts I had to make because of vocal lines, that sort of thing. That was it. You don’t change the length, you just adjust the cuts.

CM: It’s common that an editor must convince a director that a favorite shot has to be eliminated because it interferes with the flow. Have you been faced with this?

TR: Oh, yes, that happens. Not only convince him that the shot has to come out, but sometimes trying to convince him that the shot he said he got, he never really did!