by Edward Landler

Written by Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright Arthur Miller, directed by Oscar winner John Huston, and starring two Hollywood legends — Clark Gable and Marilyn Monroe — The Misfits premiered in New York City February 1, 1961.

The difficulties surrounding the shoot slowed production, adding over a half million dollars to the budget and giving United Artists’ publicity campaign an unwelcome notoriety. The picture went on to gross a then-impressive $1.2 million during its first weekend of release in 145 theatres. With mixed reviews, though, it only took in about $4.1 million during its entire initial run, not much over its final $4 million budget — “a lot of money in those days for a black-and-white film,” said director Huston in his 1980 autobiography, An Open Book.

Yet The Misfits endures as a powerful exposition of America’s failed aspirations to love and to fulfilling work. The collaboration of the personalities involved created a movie that resonates today more greatly than how the sum of its parts were viewed 55 years ago through the lens of a troubled production.

The idea for the film was sparked early in 1956 when Miller established residency in Nevada to divorce his first wife. Staying outside Reno, he hung out with a veteran cowboy, a part-time auto mechanic who owned a Piper Cub, and a rodeo rider. The three took the writer out to watch them capture wild horses to be slaughtered for dog food, and they talked a lot about a young woman the three of them all knew.

After getting his divorce, America’s foremost playwright married Monroe, Hollywood’s most prominent sex goddess, on June 29, 1956. Variety announced their wedding with the headline: “Egghead Weds Hourglass.” In 1957, while in London with Monroe to film Laurence Olivier’s The Prince and the Showgirl, Miller wrote a short story about three Nevada cowboys hunting mustangs and reflecting on their experiences with a young divorcée to whom they were all attracted.

The story, titled “The Misfits,” appeared in Esquire magazine in October 1957. Miller saw it as “a story of three men who cannot locate a home on earth for themselves…and a woman as homeless as they but whose intact sense of life’s sacredness suggests a meaning for existence…”

In January 1958, back in New York, Monroe lost a child early in pregnancy. Miller, in his 1987 memoir Timebends: A Life, recalled a friend, photographer Sam Shaw, visiting with them in the hospital. Shaw told Miller that he thought his short story “would make a great movie and…a woman’s part she could kick into the stands.”

A few days later, the writer started expanding the story into a screenplay as “a kind of a gift…the expression of a kind of belief in her as an actress… Whatever Marilyn was, she was not indifferent; her very pain bespoke life and the wrestling with the angel of death.”

Nearing the end of the first draft in July 1958, Miller thought of Huston to direct. Recognizing Monroe’s potential, the director had cast her in The Asphalt Jungle (1950) at MGM, causing 20th Century-Fox to put her back under contract. Miller wrote that the director “was one of her few good Hollywood memories.”

Miller shared the completed draft with Frank Taylor, editor-in-chief at Dell Books. Taylor had worked in Hollywood for a few years and produced Mystery Street (1950) at MGM, where he got to know Huston. Volunteering to produce The Misfits, Taylor sent the script to the filmmaker who agreed to direct immediately.

By the early part of 1959, Lew Wasserman of MCA (three years before acquiring Universal) had lined up Gable, Montgomery Clift, Eli Wallach and Thelma Ritter for the cast. Their contracts, combined with Huston’s, Monroe’s and Miller’s, brought the above-the-line budget alone to more than $2 million.

Scheduled for a September 1959, shoot in Nevada locations, the start was delayed because of conflicts for the principals. Monroe’s Fox contract committed her to star with Yves Montand in Let’s Make Love (1960), directed by George Cukor, and Gable had signed to do It Happened in Naples (1960) with Sophia Loren.

Production finally began on July 18, 1960. The night before, the director had asked the native Paiutes of Pyramid Lake to perform a rite for good weather. An hour later it rained. The real problems, though, were temperatures rising to 110° and further delays caused by a company flu epidemic, Huston’s emphysema and gout, a forest fire, Monroe’s state of mind and the deterioration of her marriage.

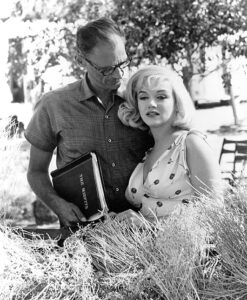

United Artists arranged for Magnum Photos to send successive pairs of its world-renowned photographers every two weeks to cover the entire shoot. Henri Cartier-Bresson and Inge Morath were Magnum’s first team. Morath’s famous portrait of star and author in their suite at Reno’s Mapes Hotel reflects the discomfort between the couple.

Production started efficiently with Huston and cinematographer Russell Metty shooting scenes around Reno a few days before the major stars’ first call dates. Less than a year earlier, Metty had shot Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus (1960), for which he would win an Oscar. Miller described him as “a tough old hand…[who] rarely used more than three lights for his shots and set them up in a matter of minutes.” The writer also liked how he gave “the film the look of a reported event rather than a fiction.”

Aware of Monroe’s reputation for being late on the set, Huston wrote in his autobiography, “I had the daily call changed from 9:00 a.m. to 10:00 a.m., hoping this would make things easier on her. It didn’t.” Still, he kept treating her respectfully as a professional in a role that had been tailored for her and tried to get her to fight through her problems with a fine performance. Monroe, however, would only discuss her performance with the personal acting coach she insisted upon for the production, Paula Strasberg, wife of Actors Studio director Lee Strasberg.

Called “Black Bart” by the crew for dressing only in black in the searing heat, Strasberg was at one point barred from the set itself by the director. Meanwhile, Monroe’s anxieties kept leading her back to the sleeping pills she thought she needed for a good night’s sleep, making it more difficult for her to find a consistent thread in her performance the next day.

Miller hoped making the film would help bring his wife and him closer together, but instead she moved out of their suite and moved in with acting coach Strasberg. Monroe would rage at him for his rewrites of the next day’s scenes. And he knew Monroe’s off-hand comment about her last scene with Gable — which would not be shot for weeks —was about their marriage: “Marilyn, with no evident emotion, almost as though it were just another script, said, ‘What they really should do is break up at the end.’”

Throughout the shoot, Gable was patient with the delays, partly because he was getting $25,000 for every day they went over schedule. Yet the well- seasoned professional was always gentle with the co-star 25 years his junior who had idolized him as a young girl. Graciously, he even kept visiting journalists entertained while she struggled to pull herself together for interviews.

Aggravated with the delays, Huston distracted himself by staying up all night at the local craps tables. The next day, he would occasionally fall asleep in his director’s chair and lose track of which scene he was shooting. Producer Taylor later told Gable biographer Lyn Tornabene that, at times like these, it was Gable’s composure and good humor that served as the guiding spirit for the production.

Despite his own drug dependency, Clift turned out to be a solidly reliable performer and Monroe formed a bond with the sensitive actor. With his help, she succeeded in completing a five-minute long conversation scene with him in six attempts, with two perfect takes. Ironically, Clift’s drug use proved to be a serious hindrance to his performance as Freud (1962) in Huston’s next feature.

Five weeks into shooting, Metty expressed concern that Monroe’s close-ups were clearly showing her drugged exhaustion. On August 27, the movie star was flown to a private hospital in Los Angeles to be weaned from barbiturates under the care of her personal physician. Using storyboards prepared by art director Stephen Grimes, second unit director Tom Shaw started shooting the horse roping scenes with stunt doubles on a dry lake bed east of Carson City, today officially known as Misfits Flat.

Meanwhile, Huston went into the cutting room to work on the first cut of what had been shot with editor George Tomasini, ACE, best known for his collaboration with Alfred Hitchcock on nine films over 10 years. Using outtakes, the editor miraculously salvaged scenes of sustained dialogue, creating coherence from material marred by Monroe’s paraphrased speeches and omissions of words and sentences.

The actress returned to Reno on September 5 and filming resumed the next day. With call times set for noon every day, the physically demanding mustang scenes with the principal actors on Misfits Flat were completed slowly over about 15 days. Despite the heat, Gable insisted on doing some of the less strenuous stunts himself.

Except for three days of retakes later in the month, October 17 was the last day on location and the company returned to Hollywood for shooting at Paramount Studios. Production wrapped on November 4, the 90th day of shooting — 40 days over schedule.

Editor Tomasini had been continuously working on the first assembly during shooting and was prepared to show most of it on that last day. Before leaving the lot, Gable told Huston, “Hell, John! If the studio is unhappy about the cost, I’ll buy this picture for $4 million. I think it’s the best thing I’ve ever done.”

Two days after, on November 6, the Oscar winner for It Happened One Night (1934) suffered a heart attack and died 10 days later. Miller later wrote to biographer Tornabene that Gable “defended the original script even after I had lost the will to and ceased to care very much except that the project be finished as well as it could be.”

Huston wanted to rush the picture into release before the end of the year for Gable’s work to qualify for Academy consideration. Alex North, the film’s composer, completed the score in three weeks but was unable to record it until December 29.

Before release, however, the film faced censorship issues concerning its treatment of animals and, of course, sex. Having supervised all of the movie’s animal scenes, the American Humane Association issued a statement which described, step by step, how the action was arranged and filmed, declaring that “no animals were cruelly treated or injured.”

The Production Code Administration objected to the “over-emphasis of nudity” and Monroe’s “bikini-type costume.” The movie received its Seal of Approval with the note: “Approved with replacement of breast shot.” Meanwhile, the Catholic Legion of Decency gave it a B rating only after the number of times Monroe’s fanny is slapped in the “paddle ball sequence” was cut down from six to two.

Oddly, these objections point up one of the central themes of The Misfits — the ways that men view women as objects. The three modern cowboys, portrayed by Gable, Clift and Wallach, relate to Monroe’s Roslyn Tabor as a creature fulfilling their own personal emotional needs — not as a human being with her own needs, concerns and desires.

Gable would have celebrated his 60th birthday on the day the movie opened. Monroe attended the New York premiere on a pass from a psychiatric hospital where she was under treatment for barbiturate dependency; 12 days earlier, she and Miller had gotten a divorce in Juarez, Mexico. The Misfits was also Monroe’s last completed picture; she died from a drug overdose on August 5, 1962.