KEN BURNS DID IT. SO DID MICHAEL MOORE. BUT A LOT OF DOCUMENTARY FILMMAKERS DON’T GO UNION. IS THAT ABOUT TO CHANGE?

By Peter Tonguette

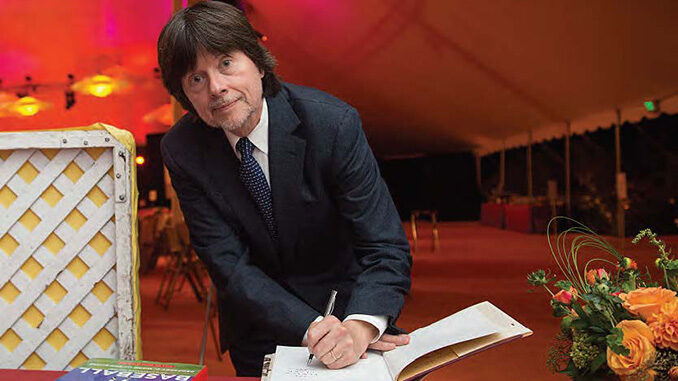

Long before he became a pop culture icon in his own right thanks to such sweeping, multipart nonfiction epics as “The Civil War” (1990), “Baseball” (1994), and “Jazz” (2001), Ken Burns was once a maker of scrappy independent documentaries.

Burns’ first and second films, “Brooklyn Bridge” (1981) and “The Shakers: Hands to Work, Hearts to God” (1984), were each hour-long examinations of fairly specialized subjects—the first, a portrait of the famous suspension bridge linking Brooklyn and Manhattan, and the second, a study of a religious movement that took root in America in the eighteenth century. Those early films had something else in common, too: Neither were unionized projects.

“In the very beginning, when I was working on my Brooklyn Bridge film, I figure I lived on about two cents an hour for about five years,” Burns said. “You can’t live on that.”

Soon enough, Burns graduated to grander subjects, larger budgets, and, significantly, union agreements. “When we began the third or fourth film, I was hiring an editor who was already in the union, and we just adopted the union rules,” Burns said. “We wanted to serve the creative people that we were hiring. . . . People are always finding contortions to avoid paying a tax on something. We just wanted to play by the rules.”

Today, Burns is among the most prominent documentarians whose projects are unionized. Despite the fact that documentaries frequently tackle social issues (including the labor movement) from a progressive point of view, a large number are made outside of the union. Industry insiders see two main issues standing in the way to increased documentary unionization—namely, the projects’ low budgets and scattered schedules.

“Obviously, it’s an additional expense for the production,” said New York-based picture editor Doug Abel, ACE, whose extensive nonfiction credits include Errol Morris’s “The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara” (2003) and the Netflix series “Tiger King.” “If I had a dime for every documentary that I started and stopped . . .”

Burns is in a unique position. Since the filmmaker has long preferred to juggle multiple documentaries simultaneously, his editors work under a term agreement rather than a single production contract. “We have a term agreement with him so it runs from a date to another date—two years, three years,” said Motion Picture Editors Guild National Executive Director Cathy Repola. “Everything that he does gets done union, by a staff he has working there, Local 700 people, at his facility.”

“We’ve just been, since 1982, in constant production with at least two projects at once,” Burns said. “It means that, for example, editors finish the Vietnam series, . . . and then moved onto ‘Country Music.’” Of course, editors are not assured of lifetime employment with the filmmaker, but some on his post-production team have had something close to that. “Paul Barnes, ACE, finally—regrettably, from our point of view—retired to the Southwest,” Burns said. “Tricia Reidy, ACE, who came as an intern in our ‘Statue of Liberty,’ is one of our senior editors.”

Yet Burns recognizes that few documentarians have such luxuries. “For some people who have not chosen the route that I’ve gone, it’s hard,” he said. “You release a film, and you don’t know what the next thing is and you spend several years raising money and maybe you have another job.”

Sound editor (and former Guild member) Midge Costin knows firsthand the benefits of union support, as well as the challenges of working without it. “When I was working non-union as a sound editor to get my hours in, they’ll just work you to death and they just don’t think about it,” said Costin, who, as a Guild member, sound-edited a series of A-list action pictures in the 1990s, including “Crimson Tide” (1995), “The Rock” (1996), and “Armageddon” (1998). After giving up her post-production career to focus on teaching at the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts, Costin rejoined the ranks of working filmmakers with her years-in-development tribute to the craft of sound editing, “Making Waves: The Art of Cinematic Sound” (2019). “I’m so passionate about sound and sound editing and sound design,” she said.

Yet, despite Costin’s passionate commitment to labor issues, “Making Waves” was made nonunion, a concession to budgetary limitations. “My main editor started out as a student of mine, and he was both a great editor and a great sound person,” Costin said. “He worked all the way through.” Yet the challenge of directing a documentary on a nonunion basis has made her reticent about proceeding with a follow-up to the acclaimed “Making Waves.” “People ask, ‘What are you going to do?’” she said. “I have a lot of subjects I’d like to do, but I’m not going this route that you eke it out just because of the love of the film.”

Beyond the question of financial restrictions, Abel points to many documentaries’ stop-and-start schedules as a major impediment to becoming unionized. “There is a lot of jumping-off—taking a hiatus, going to a fundraising stage, somebody takes another gig—unlike even an indie feature, [which is] an intense five or six weeks of shooting and then three months of cutting,” Abel said. “Documentaries tend to be more all over the place.”

Such scattershot filmmaking makes unionizing documentaries a particularly thorny challenge, Repola said. Since the Editors Guild is affiliated with IATSE, documentaries cannot be organized during the post-production phase; instead, the project has to have been unionized from the get-go. “If it was shot anywhere in the United States or Canada, which is where the IA has jurisdiction, it has to cover the production also,” Repola said.

In fact, the only union documentaries Abel has ever cut are those of Oscar-winning “Roger & Me” filmmaker Michael Moore, who, like Burns, is a major player in nonfiction film and thus something of an outlier. “Part of that, frankly, is because some of [Moore’s] subject matter has to do with unions,” Abel said of Moore’s decision to go union. “He got to a point in his career where he could just build it into the budget,” said Abel, who worked on episodes of Moore’s late-1990s TV series “The Awful Truth” and, most recently, the director’s feature-length documentary “Fahrenheit 9/11” (2018).

Picture editor David Tedeschi, ACE, describes a similar catch-as-catch-can environment for many post-production professionals looking to work in documentaries. “A lot of films are passion projects but start very slowly,” said Tedeschi, who also lives in New York. “Maybe they’ll hire an editor for a couple months, or maybe they’ll think that they’re bringing on the editor just for the last month but it turns into a year.”

Understandably, many editors early in their careers just want to work on stimulating projects, regardless of their union status (or lack thereof). “When you’re 30 years old, or even 40 years old, you don’t necessarily see that benefits are necessary,” Tedeschi said. “Especially in New York, you can slip in and out of getting healthcare; there are work-arounds in clinics. But it’s only now, past 50, that I really think about: ‘Oh, right, It’s nice to have those retirement benefits.’”

Since the mid-2000s, however, Tedeschi has been working almost exclusively on the documentary projects of Martin Scorsese, which, as with Burns’s or Moore’s editors, puts him in a uniquely advantageous position. “They’re good to me,” said Tedeschi, whose credits include “Shine a Light” (2008), “Public Speaking” (2010), and “George Harrison: Living in the Material World” (2011), the last of which netted him Primetime Emmy and ACE Eddie nominations. “First of all, [Scorsese’s] company is a signatory. . . . They’re very open to the Editors Guild. And I’m very strong about it. It’s made a real difference in my life.”

But what about the countless low-budget documentaries made on both coasts each year? For them, the story is less upbeat. “I have a very good friend—she’s a great nonfiction editor—who hasn’t done a union job in a long time,” Tedeschi said. “Years—like over ten years. I asked her about it once. She said, ‘No one will pay my benefits,’ which is heartbreaking.”

There are reasons to hope. Tedeschi said that he has noted an uptick in union interest in recent years. “I went to a union meeting maybe a year-and-a-half ago for the first time in a long time, and I was shocked how many young people there were,” Tedeschi said. And before the pandemic swallowed up so much time and energy, the Guild itself had been emphasizing the need to bring more documentaries under contract early in the process.

“We are in discussion with Local 600 [International] Cinematographers Guild about how we might close that loop so that we can get our foot in the door sooner, if we could be more proactive with reaching out when production starts,” said Repola, who added that Editors Guild Eastern Executive Director Paul Moore has been successful in getting New York-shot documentaries under contract. “When they’re shooting in New York, we’ve managed to get deals done somehow,” Repola said. “I think the universe is a little smaller. If you’re shooting a documentary in New York City, everybody knows it.”

For his part, Burns describes the Guild as eager to find solutions for his team of editors—and to assure that his classic documentaries continue to be union-made. “We’ve been able to appeal to them and say, ‘Look, we’re planning to keep [editors]on not for a three-month job, not for a four-month job, not for a six-month job, but a two-year job,’” Burns said. “They have been willing to work with us.”