by Kevin Lewis

The sound editing and mixing of The War involved some of the best sound people in the industry. Though many documentary producers cut corners on sound editing, relegating it to the bottom of the production budget, filmmaker Ken Burns is the opposite, according to sound editor Marlena Grzaslewicz, who claims that he takes this aspect very seriously and puts together a first-class team.

In the long run, this pays off because, as fellow sound editor Ira Spiegel adds, “Ken is a very shrewd businessman who stays within his budget.” Working with Spiegel and Grzaslewicz is Mariusz Glabinski, a young sound editor and designer who is a specialist in background sounds and sound effects. Spiegel recorded German, Italian and American voices, as well as cannon sounds, while Glabinski recorded Japanese voices and Grzaslewicz recorded dialogue.

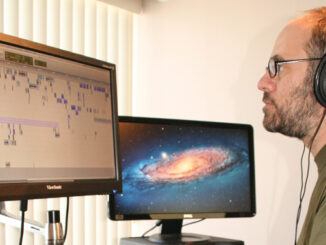

The person who brings all of their talents together in a seamless landscape–– and in the case of The War, a battle-scarred soundscape––is Oscar-winning re-recording mixer Dominick Tavella, CAS. “On the first pass we do, I record the narration, voiceover and music that has been assembled in ProTools, using the Avid as a guide,” he says.

In the case of archive footage, Tavella took the sound collected or recorded by Spiegel, Glabinski and Grzaslewski and decided how to use the archive material, replete with the pops, buzzes and static from the World War II period. He either incorporated the original sound and digitally edited out the pops and noise, or used it as a rough guide for newly recorded sounds.

“I mix in 5.1 surround,” Tavella says. “The vast majority of sound has to be re-created from scratch by the sound editors.” Spiegel and Grzaslewicz deliver the audio in ProTools. “We run it through a Neve DFC console, using Digibeta or QuickTime,” he adds. “We wanted to make the audio in the battle scenes as visceral as possible, and to get into the heads of the soldiers in the trenches, so we’ve got to do this in 5.1.”

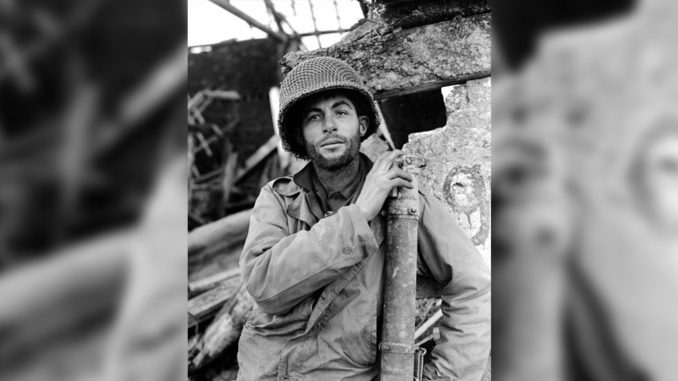

Using surround sound in a documentary requires a different approach than in feature films, according to Tavella. “If you are working in a fictional narrative, you’re trying to get sounds for specific dramatic values,” he explains. “In documentary, we want to be as realistic as we can. What’s it like to be in that picture? That always has been Ken Burns’ approach to audio.

“The War is so dense in the battle scenes that the real mixing challenge is paring the sound down so you have a sense of the individual but never lose the sense of the chaos surrounding that individual,” Tavella continues. “One of the most interesting things about the film is that we did it in a layered way. We did the dialogue and music first, then the sound effects for the second pass, and our final balance for the third pass.”

Tavella and the sound editing team worked tirelessly to make each bomb explosion sound different from the previous one. The silences in between would create a mounting tension of anticipation. “A bomb explosion would be composed of six or eights effects,” he explains. “The American weaponry sounded different from the German weaponry, and the Japanese weaponry sounded different from both of them.” Incredibly, all of this perfection for a 14-and-a-half-hour film was achieved in less time than would be typical in a two-hour big budget feature film. “We squeezed a ten-week mix into two weeks,” Tavella says.