by Bill Desowitz • portraits by Gregory Schwartz

In yet another summer dominated by comic book superheroes, Thor (opening May 6 from Paramount) stands out both for its Norse mythology and its choice of directors: the distinguished Kenneth Branagh (Hamlet, Henry V). Based on the legend of the Thunder god, the Marvel Comics adaptation concerns the Mighty Thor (Chris Hemsworth), a powerful but reckless warrior who reignites an ancient war. As punishment, Thor is cast down to Earth, where he must fight the darkest forces of his world, Asgard. Thus, unlike other Marvel protagonists, the hammer-wielding Thor starts out as a superhero and becomes human as part of a necessary humbling process.

The Norse myths have existed in written form since at least the 13th century. Thor first appeared in a comic book in 1962. Thus, the comic book story has had various incarnations in its 50 years, so it was challenging for Marvel to settle on the version it wanted to film. Once it was decided that Asgard and Earth (or Midgard, as the gods call it) would both be in the film, making it an origin story, the tricky part was settling on the tone of the interactions.

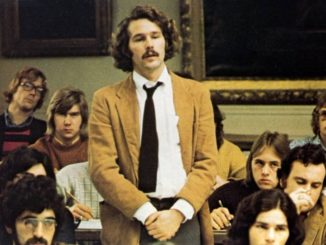

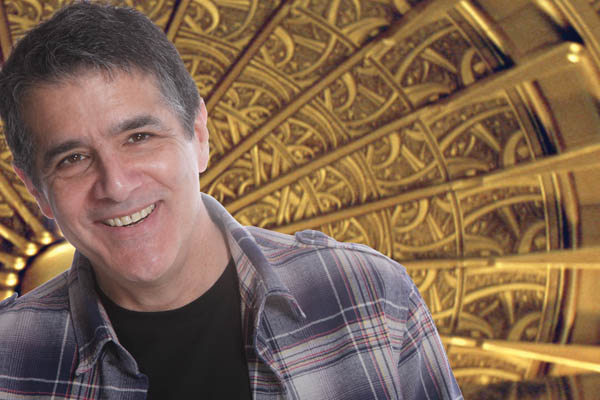

The film’s editor, Paul Rubell, ACE, has cut his share of superhero features, including the first two Transformers films (2007 and 2009), Hancock (2008) and Blade (1998). “There is an element of gravitas in Thor that one doesn’t necessarily associate with a movie based on a comic book,” he claims. “And this is juxtaposed with laugh-out-loud humor. The ability to juggle those two tones is one of Kenneth Branagh’s great strengths, and is somewhat unusual for this kind of movie.”

In fact, Thor creates a situation that exposes him to the wrath of his father, Odin (played by Anthony Hopkins). This leads to his discovery on Earth by a group of scientists who must deal with a man claiming to be a god. “It’s a very funny scene, but when it comes on the heels of such intensity, the audience isn’t instantly clear that it’s okay to laugh,” Rubell continues. “That sort of transition had to be played with. The tone of Asgard is generally more dramatic, while Midgard is lighter in tone.”

While many people may think the choice of Branagh as the film’s director was counterintuitive, the editor contrarily insists it was the perfect match. “In addition to having directed more than a dozen movies in the dramatic, comedy, mystery, science-fiction and musical genres, his background is Shakespearean theatre–– and there are aspects to the Norse gods’ family relationships that are Shakespearean in scale and tone. People have been drawn to entertaining stories about dysfunctional families for hundreds of years. Throw the worlds of Asgard, Earth and Jotunheim [one of the Nine Realms of Asgard] into the mix, and you’ve got an intimate foreground story set against an epic background.”

Additionally, Branagh is a master at directing for performance, the editor emphasizes. “He has acted in more than 50 film or TV roles and numerous stage productions,” Rubell says. “So he’s not going to be intimidated by Anthony Hopkins! And he’s going to guide less experienced actors to fine performances.” In addition to Hopkins as Odin (who’s got two high-spirited kids to deal with while trying to run the Nine Realms on a daily basis), there’s also Tom Hiddleston as Loki, Thor’s adoptive brother and nemesis––who would have benefitted from Norse psychoanalysis––and recent Oscar winner Natalie Portman as Jane Foster, a scientist who must confront an ancient myth.

“As an actor, Ken knows in his DNA which moments are genuine and which are, however skillfully delivered, artifice,” Rubell explains. “With Loki, in particular, it was impossible in the shooting to judge how to orchestrate the reveal of his changing nature over the course of the entire movie, so Ken shot a wide range of options. It took a while to hit on the right combination of dynamics.”

When it came to newcomer Hemsworth, Branagh’s strategy was to help him humanize Thor as much as possible. “Without giving anything away, the thing that attracted me most about this story was the idea that a Norse god interacts with humans in the 21st century,” Rubell says. “How do you tell this story without being ridiculous? Chris and Ken and the writers [Ashley Edward Miller, Zack Stentz and Don Payne] realized that tone beautifully.

“The trick was to present a character that lacks humility, yet is appealing enough to carry the movie until the change comes,” he continues. “A less appealing character makes for a more effective redemption––but it’s not as much fun to watch. So we were constantly tweaking the performance and swapping scripted moments in and out of the movie in search of the delicate balance.”

And as for Thor’s look and fighting style? “Suffice it to say that it’s not just a guy in a cape swinging a hammer,” the editor replies.

Indeed, the effects-intensive Thor contains around 1,300 visual effects shots, which range from Asgard and Jotunheim backgrounds to creature animation. “Imagine a ten-foot, flame-throwing metal juggernaut,” Rubell offers. “Or a gigantic ice beast that’s been hibernating for centuries until now. Or a race of frost giants.” These were the kinds of challenges faced by effects supervisor and Guild member Wes Sewell and his extraordinary team.

“I started three months before production, working with the pre-viz department, headed by Gerardo Ramirez, which morphed into the post-viz department as soon as we started shooting,” Rubell continues. “We had a minimum of three post-viz artists, and sometimes as many as six, until quite late in post-production. This allowed us to initially flesh out the script, and eventually to revise the action as necessary in response to the evolving demands of the story. Ken is extremely well organized, and he took to this process like a CG duck to CG water. He worked intimately with our storyboard artists, particularly Rico D’Alessandro, during pre-production to put his visual stamp on the visual effects/action sequences.”

Rubell also discusses the numerous hurdles in editing Thor: “The biggest challenges were juggling the range of tones and settling on the right amount of back story needed to jump into a complex mythological world.” As an example, he offers, “In the comics, Thor’s warrior friends were very broadly drawn, even bordering on slapstick at times. We spent quite a lot of time modulating this in the film. And we eventually added a kind of prologue, which sets the historical scene so that the audience doesn’t have to work quite so hard to catch up with the story and characters.”

For his part, director Branagh is “an angel” in the cutting room, according to Rubell. “It will come as no surprise to his fans to hear that he is impeccably cultured and articulate––but I was surprised to find that he is drop-dead, hysterically funny,” he says. “Early on, we decided that the most efficient way to work was for him to convey his notes to me; then go away while I conjured up various versions.” This process allowed Branagh to retain a little more objectivity, while giving Rubell the freedom to experiment––and perhaps surprise the director on occasion.

“We successfully merged our waveforms,” he adds. “I tended to cut long in the first instance––although it didn’t feel long at the time––whereas Ken functioned as a conductor, beating out a faster tempo until things began to resonate at their own frequency.

“What I love about the editing process is that it’s dialectical: thesis, antithesis, synthesis,” continues Rubell. “And that by the time ideas have been synthesized, they have been purified of ownership. As editors, we learn to play our editing systems––in my case, Avid Media Composer––like a piano, so the rhythm is essentially ours. Although it’s dictated, of course, by the rhythms of image and dialogue, which flow from principal photography.”

When asked about Thor’s highlights, Rubell merely reveals, “Fights! Romance! Drama! Comedy! More fights!”

Thor actually represents a first for Rubell: His 18-month stint in the edit suite is the longest he’s been immersed in one story, which means “the potential of over-familiarity and editing your way past the best version of the movie,” he says. “But I think we avoided that pitfall.” It’s also the first movie in many years that he has cut solo. “I missed the collaboration, and the luxury of being able to walk into my co-editor’s room and get an expert, objective, no-holds-barred opinion on a scene,” he explains. “With Thor, that role was filled by my stellar assistants, Rob Malina, Leslie Webb and Rich Conkling, as well as visual effects editors Jeremy Bradley and Danny Rafic. But on the other hand, it’s immensely gratifying to have the entire movie filtered through my own personal aesthetic.”

But there was another component to deal with on Thor: stereoscopic 3-D conversion. Completely CG shots were delivered by the visual effects vendor as true 3-D, while shots that mix live-action plates with CG effects were first converted, and then the 3-D effects were added.

“We did some things differently from the way conversions have been done in the past,” Rubell explains. “For example, whatever is of primary interest in the frame we took to the screen plane. This pushes foreground objects into negative space [toward the audience], which in the past has been uncomfortable to view. But we compressed the foreground objects to collapse their volume––which can’t be accomplished in stereo photography––and make the frame more natural. We also created floating windows to soften how the eye perceives the edges.”

When asked about Thor’s highlights, Rubell merely reveals, “Fights! Romance! Drama! Comedy! More fights!” And how will the character segue into next year’s film about a team of superheroes, The Avengers, which Rubell will also be editing? “Thor will flow seamlessly into The Avengers.”

‘Nuff said, as Marvel comic book characters are wont to exclaim.

Bill Desowitz is senior editor of AWN and VFXWorld, and has contributed to The Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, Wired, Fandango and Variety, among others. He can be reached at bill@awn.com.