By Betsy McLane

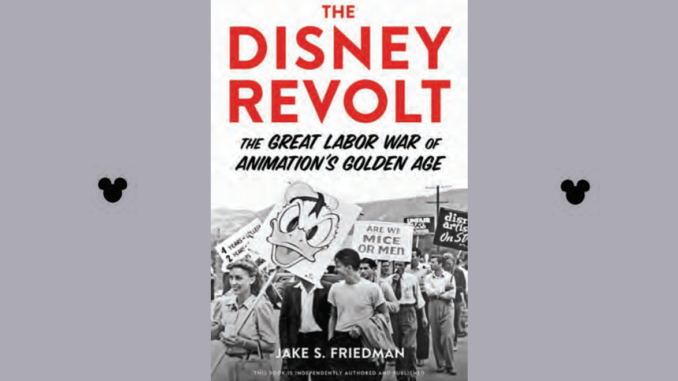

Jake Friedman deserves a rousing hurrah for writing “The Disney Revolt: The Great Labor War of Animation’s Golden Age.” This is an eye-opening book full of many fascinating stories about a World War II-era Hollywood labor battle, and even readers who are familiar with the history of animation, or the growth of entertainment industry unions, will discover something new in its pages. As Leonard Maltin, the film expert and author of “Of Mice and Magic: A History of American Animated Cartoons,” wrote, “I learned many things I didn’t know from this treatise, which allows the reader to make up his or her mind about the still-simmering divisions caused by the dispute.” Maltin is correct in calling this a treatise, but it is an absorbing one.

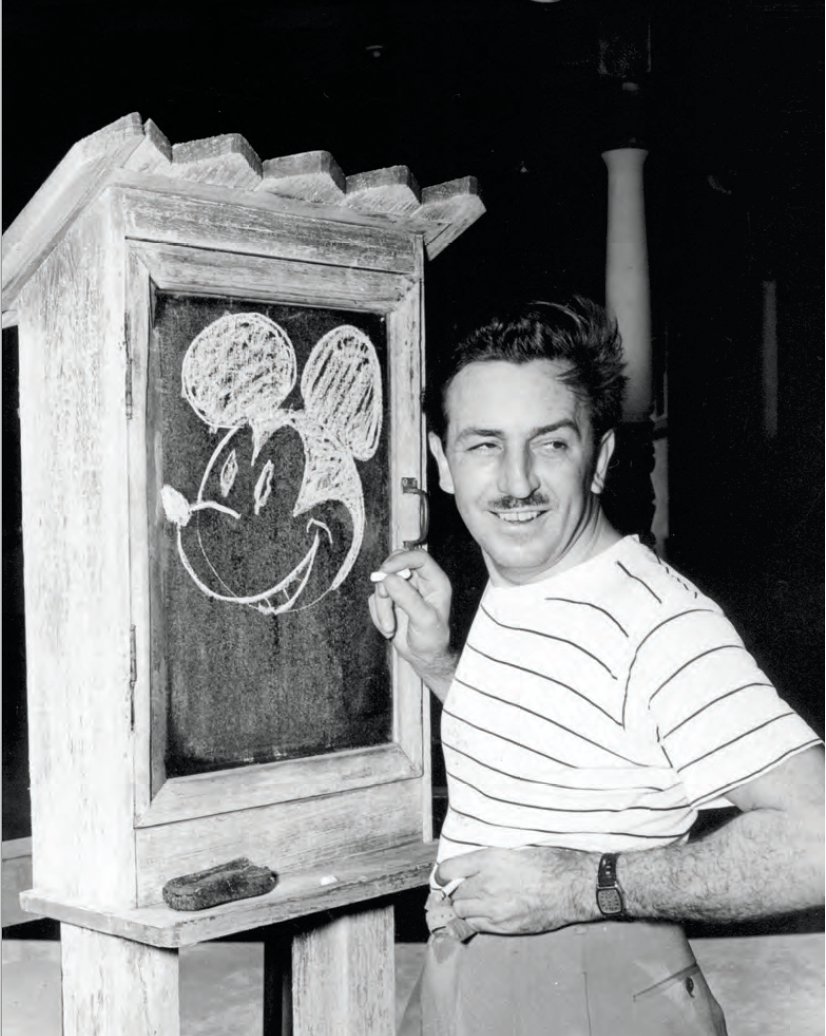

The history of the 1941 Disney animators strike as laid out by Friedman is dramatic and filled with enough twists to make for a page-turner. He structures the narrative around the backgrounds, personalities, and career intersection of two central figures, the animator Art Babbitt and Walt Disney himself. Walter, born 1901, and Arthur (b. 1903) shared more than Midwestern childhoods: Chicago, a family farm in the small town of Marceline, Mo., and Kansas City for Walt; Omaha, Sioux City, and then New York City for Art. They both also had early exposure to labor organizing and social injustices. Friedman describes each man’s formative years amid the social background of the time: labor unrest, Eastern European immigration, and World War I. He draws on their early experiences with family, work, responsibility and organized labor to help explain why decades later they became first colleagues, then enemies.

Walt’s father Elias Disney was a supporter of the socialist politician Eugene Debs, one of the founders of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or The Wobblies) and was active in the populist/socialist movements that roiled American politics at the turn of that century. Solomon Babitsky, Art’s father, was an immigrant from Eastern Europe, a Jewish scholar who had no skills that were marketable in the US. Neither man provided financial stability, and both boys had to work to help support their families, eventually rebelling against their ineffectual fathers. The artistic talents that Walt and Art displayed while young were encouraged by the women in their lives, Walt’s aunt Maggie and Art’s mother Zelda. Solomon Babitsky was disabled in a work accident in 1923, and the family moved to New York, where it was forced to be increasingly dependent on Zelda’s family. Art rejected his father’s strict religious doctrines, and by fiercely standing up for his rights as an employee, found success as an advertising artist. Walt felt that his father, known as a “churchy” man, was a gullible pacifist, misused by a disreputable socialist farmers’ cooperative. At age 16, when a bomb attributed to the IWW exploded close to him in the Chicago Federal Building, Walt decisively turned against Elias and joined the war effort as an ambulance driver.

The family atmosphere of Disney morphed into paternalism.

These facts, and a great deal of other information presented in the first five chapters of “The Disney Revolt,” may make it appear that psychological analysis will dominate the book, but this is not the case. While Friedman does refer to the possible emotional states of some of those involved in the strike and sets their careers within the context of their personal lives, he fortunately does not wander into fanciful supposition. The book avoids specious speculation, an approach that creates trust in its authenticity. Even so, readers would have benefitted from a pictorial timeline that clarified the complicated events.

A simplified explanation of the strike is that the close-knit family atmosphere that characterized the earliest days of Disney cartoons morphed into a kindly paternalistic organization as Mickey Mouse and his pals rose to fame. Then as the studio moved from Hyperion Avenue in Hollywood to grand new facilities in Burbank and was riding high on the success of Hollywood’s first animated feature film, “Snow White,” the hiring of hundreds of workers, mounting debt, grueling production schedules, broken promises, low pay and hard-nosed bureaucracy drove star animators like Babbitt to feel increasingly sidelined and underappreciated. Babbitt was held in high esteem by the creative community for animating classic characters like Goofy, the evil stepmother in “Snow White,” the Chinese Dance in “Fantasia,” and Geppetto in “Pinocchio.” He developed a technique with his personal camera for filming “action analysis,” in which the actual movements of people were transferred to cartoon characters, giving them unique dimension and personality.

Although Babbitt was the studio’s highest-paid animator, he was passionate about getting decent money and working conditions for the lowest-paid employees. The studio’s pay scale was erratic; the highest-ranking animators made as much as $300 a week, while many lower-ranking film workers earned as little as $12. A mysteriously arbitrary bonus system added to the confusion. Babbitt refused to join an exclusive club on the Disney lot because it would not admit anyone who earned less than $100 a week. While working at Disney Studios was considered the prime artistic opportunity in the 1930s, animation, employees there were the lowest-paid in Hollywood. Many of the crafts, including The Society of Film Editors, were already unionized, and the large national unions, the American Federation of Labor (AFL), the Congress of Industrial Workers (CIO), and especially the International Alliance of Theatrical and Stage Employees (IATSE) were all trying to expand their influence in Hollywood.

Babbitt was the acknowledged head of the 1941 strike, but an enormous number of factors led to it, and various versions of what happened when, and who did what to whom, and why, have been written and talked about for decades. Friedman seeks to uncomplicate the baffling amount of information surrounding his subject by wisely avoiding reliance on previous books and instead cites recorded interviews, legal documents, contemporary publications (especially major newspapers and the trade press) letters, and thousands of what must have been mind-numbing records from the National Labor Relations Board. He is a thorough historian, using massive numbers of primary sources in research conducted over 10 years to explain an extremely complicated situation.

Through Friedman’s efforts the roles of numerous individuals become clearer. One was Disney’s Chief Legal Counsel, Gunther Lessing, whose most famous client had been Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa for whom he negotiated a $25,000 film contract. In late 1938, Lessing and Babbitt concocted a “fake” in-house union, the Federation of Screen Cartoonists, meant to block the IATSE from gaining control at the studio. Babbitt and others soon realized that this organization was simply a management tool, and by 1941, Lessing was considered the main obstacle between Walt and a compromise with the legitimate Screen Cartoonists Guild. The other major player in the saga was Willie Bioff. Bioff was a convicted Chicago gangster who partnered with IATSE Chicago President George Brown to bilk theater owners. With the help of Al Capone’s men, Brown became National President of IATSE, and because most theater projectionists were IATSE members, Bioff and Brown were able to extort huge sums of money from Hollywood studios by threatening projectionist strikes. This technique played a strategic role in the Disney strike.

“The Disney Revolt” explains the machinations these men engaged in, as well as the shifting relationships among artists, employees, management, lawyers, the federal government, and friends. It does so with an easy readability that belies the thoroughness of Friedman’s work. Photographs and cartoon drawings are scattered throughout, each of which deserves attention. While the book does not dwell on the repercussions of the successful strike, it does briefly follow up on the lives of each major player. In 1943, the gangsters behind the IATSE were indicted for extortion of more than $1 million from the biggest studios and charged with fraud against the stagehands and projectionists. Friedman does not point a finger at Walt Disney for his possible antisemitic beliefs, pointing out that Disney worked with many Jews. Nor does he excoriate Walt for testifying and naming names before the Congressional House Unamerican Activities Committee in 1947. Three of the men he named were business managers of the Screen Cartoonists Guild, and the fourth was Dave Hilberman, a layout artist at the studio and a strike leader who was indeed a Communist. Still, within the industry, Walt Disney’s name was tarnished by accusations of prejudice.

Friedman does not follow up on the long-lasting animosity that existed for decades between strikers and non-supporters of the union. He presents Babbitt as the stronger, more principled of the two men, and the vitriol between them is almost glossed over in the final chapter, where he notes Babbitt’s 2007 posthumous honor of being designated a Disney Legend, joining the company’s official “hall of fame.” Art Babbitt died in 1992, living more than a quarter-century after Walt Disney’s death in 1966. Babbitt ultimately became a much-revered elder of animation, influencing many artists. Disney became a mythic hero, the namesake of a huge corporation and a household name for millions of fans. Each man, in his own way, was forever marked by the strike. It is difficult to know whether either would have liked the Disney Legend designation. It is even harder to imagine what they might make of more recent events, such as the March 2022 walkout of some Disney employees in support of LGBTQ rights.

The Disney Revolt: The Great Labor

War of Animation’s Golden Age

By Jake S. Friedman

322 pages

2022 Chicago Review Press