by Rob Callahan

The start of a new year prompts us to step back momentarily from our day-to-day concerns, reflect upon the long view, and make resolutions for our future.

This column affords a similar opportunity to take stock of the bigger picture. Ordinarily we focus on what post-production employees have accomplished through their solidarity, but let’s cut from our usual close-ups of Local 700 organizing to a wide shot of the state of the American labor movement.

You likely knew this already: The state of our unions is not good. Indeed, the decline of the labor movement in the United States isn’t a breaking news story flashing across our consciousness with the speed of a trending hashtag; it’s a prolonged and plodding crisis that is older than most of our members, a slow-motion catastrophe as protracted and seemingly intractable as the melting of polar ice.

Frequently cited statistics quantify the atrophy of US unionism. Fewer than 12 percent of wage and salary workers in the nation are now represented by unions — down from a peak of nearly 35 percent some 60 years ago. Looking at the private sector alone, an even more dismal picture emerges: Union density at private employers has dropped below 7 percent.

Membership statistics only tell part of the story, but what they don’t tell isn’t necessarily more reassuring. By any meaningful measure, organized labor enjoys less clout in both the workplace and the political arena than we once did. Wage stagnation and growing income inequality have closely tracked this loss of influence. Many credit organized labor with having largely built the American middle class, and it’s no mere coincidence that its imperilment parallels labor’s wane.

Our power is so diminished that, in recent years, we have been subject to a barrage of political attacks of shocking virulence. Governors and state legislatures have assailed collective bargaining rights, and pushed so-called “right-to-work” laws engineered to weaken unions. At the federal level, anti-labor forces in the House and Senate have sought to hamstring the already largely toothless National Labor Relations Board, the federal agency charged with enforcing the right to collective bargaining. Corporate interests have mounted legal challenges to workers’ rights in the courts.

That, in very broad strokes, is the bad news. Imagine a dystopian near-future of alienated workers — stripped of their aspirations, burdened by debts they can never repay, subject to the whims of their oligarch overlords. We’ve seen that movie, and it’s looking less and less like science fiction and more like a documentary.

So, if organized labor is imperiled but remains important to the prosperity and happiness of working folks, how might we reclaim the strength we’ve lost over the course of many decades?

Our situation is sufficiently dire that many of labor’s enemies now voice public doubts about whether unions will retain any relevance whatsoever in the new economy to come. With the diminishment of the manufacturing sector, the ascendency of the service and information sectors, and the increasing casualization of middle class employment, opponents of organized labor say, unions are anachronistic vestiges of the industrial age, relics that have outlived their utility.

Unions have not yet, in fact, lost all relevance. What we do makes a difference. Plenty of studies have shown that union representation yields material improvements in employees’ lives — improvements that take the form of higher pay, better access to health care, stronger retirement benefits, reduced racial and gender disparities in wages, and a host of other concrete advantages. Moreover, above and beyond these substantive improvements in employees’ lives, recent research demonstrates that unions contribute to their members’ subjective sense of well-being.

Late last year, social scientists at Baylor University and the University of Arkansas published a study documenting a strong correlation between union membership and quality of life. Even after the researchers controlled for other variables such as income, health, education and demographic factors, union members reported significantly higher levels of overall satisfaction than non-members. The researchers theorize that this elevated satisfaction derives from having a greater voice in the workplace — from enjoying greater security in one’s career, from being part of a more closely knit community of colleagues, and from a greater degree of civic engagement. Whatever the underlying mechanisms, the outcome is clear: Union membership, apart from its material rewards, contributes to our happiness.

So, if organized labor is imperiled but remains important to the prosperity and happiness of working folks, how might we reclaim the strength we’ve lost over the course of many decades? The question has long occasioned handwringing amongst our best thinkers, as labor’s strategists ponder how to ensure the future relevance of a movement both battered and vital. There’s widespread recognition within the labor’s ranks that evolution is the only alternative to extinction, hence the emergence of what is often referred to loosely as “alt-labor” — an array of innovative strategies and structures that depart from the conventions reified in organized labor’s post-war heyday.

The only thing that can save our movement is the only thing that ever has: folks making common cause with their co-workers and neighbors, finding in solidarity a power greater than that of those who would hold us back.

Interestingly, the most exciting alt-labor projects take inspiration from labor’s past in imagining how best to move forward. Experiments in minority unionism, for example, represent one such instance of borrowing from history to fashion a future. Minority unionism — the practice of campaigning for improved conditions without first obtaining support from a majority of employees at a given workplace — had been largely dismissed as obsolete since 1935, when the passage of the Wagner Act established a legal mechanism for unions to be elected the exclusive representative of an employer’s workforce. But new organizations such as OUR Walmart and Fast Food Forward have recently revived the strategy of minority unionism by mounting high-profile campaigns for better jobs, without first building majorities at targeted employers. The United Auto Workers, too, is experimenting with minority unionism by pursuing informal negotiations at a Volkswagen plant in Tennessee, where it narrowly lost a recent election (after anti-union politicians publicly threatened to revoke tax incentives if Volkswagen’s workers voted to unionize).

Our industry, too, affords examples of new hopes scavenged from old traditions. The labor market in the entertainment industry looks a lot like the future of middle class work in the emergent paradigm of the US economy: a pool of casual or contingent workers, educated and possessed of specialized technical or artistic skills, without any stable, long-term relationship to a single employer. These are precisely the sort of workers who have outgrown the need for unions, in the opinion of labor’s detractors, or whose dispersal renders impossible the prospect for collective action, in the opinion of some of our friends.

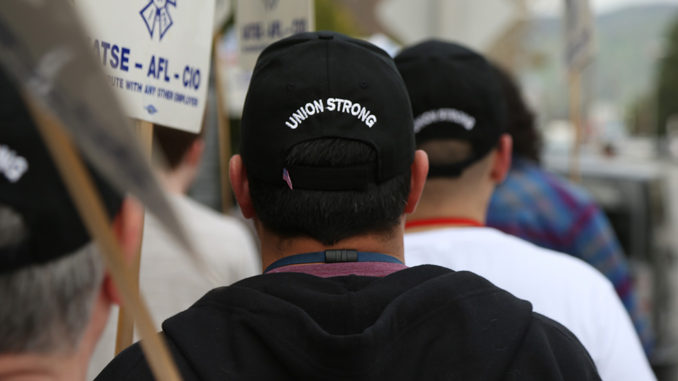

But our Guild and the IATSE have demonstrated that these paradigmatic new economy workers can indeed organize, and that they can do so using decidedly old-school strategies. Several of our recent organizing efforts have made effective use of recognition strikes, another organizing tactic that went largely out of style with the passage of the Wagner Act 80 years ago.

Plenty of studies have shown that union representation yields material improvements in employees’ lives — improvements that take the form of higher pay, better access to health care, stronger retirement benefits, reduced racial and gender disparities in wages, and a host of other concrete advantages.

Although the picture is bleak, it’s not uniformly so. A wave of local and state initiatives to raise the minimum wage, fueled by alt-labor organizing, has found traction. And the NLRB’s recent tweaking of certain regulations might afford some modicum of additional protection to workers seeking to organize.

However, we ultimately won’t be rescued by friendly politicians or bureaucrats. And alt-labor innovators will continue to devise creative ways to amass collective power, but we won’t find salvation on a social media site or smartphone app. The only thing that can save our movement is the only thing that ever has: folks making common cause with their co-workers and neighbors, finding in solidarity a power greater than that of those who would hold us back.

The cliffhanger is perhaps a tired trope in this era of video-on-demand and binge viewing, but you’ll need to keep tuning in later to see how this story unfolds and what becomes of our embattled labor movement. More importantly, you’ll need to keep standing up, standing together, and dismissing the naysayers who claim it’s passé to do so.

The state of the American labor movement looks bad, but we’ve all seen the movie in which the nearly defeated underdog gets up, fights back and wins. We can make that movie, but it’ll take a large and talented supporting cast.