By Presley Balholm

A confession: As a child, I used to duct-tape a tape recorder to the bottom of our kitchen table, leaving it there to collect the day’s gossip that I later studied and disseminated at will. (‘Spying!’ you exclaim, wagging a punitive finger at me. No, dear reader: character analysis). I’ll plead to a certain impulse towards self-preservation. As the only girl in the family, I required ammo. Blackmail proved as effective a weapon as any. My hands were kept clean, the bruises were invisible and should either of my brothers step out of line, I had verifiable proof of their misdeeds. Beneath this streak of childhood nastiness was a far more banal truth: I liked words. I was fascinated by the individual rhythms of speech, the mysterious spaces between that which was spoken and that which was not, the double meanings, the verbal feints and parries. There was a war going on, and conversation was the battleground.

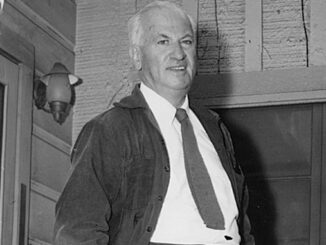

A consequence of growing up: Eventually, you develop a conscience. At some point, I submitted to becoming a respectable member of society. Still, my appetite for cruelty (fictional, of course) never waned. Then, as now, I liked my stories filled with meanness. The inflection point came in the form of Alexander Mackendrick’s 1957 noir “Sweet Smell of Success,” where words are as lethal as bullets.

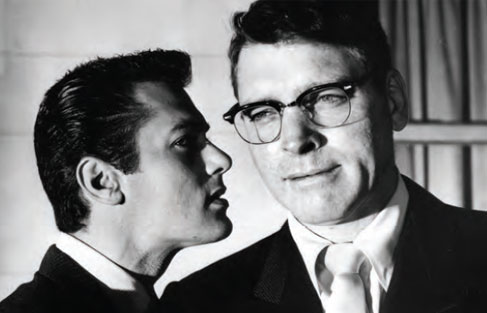

The players: Sidney Falco, played by Tony Curtis as the human embodiment of a sneer. With a twitchy, obsequious charm that all but oozes off the screen, Curtis’ press agent plays acolyte to Burt Lancaster’s J.J. Hunsecker. A familiar monster to anyone with even a passing knowledge of the entertainment industry, Hunsecker is a domineering columnist and tastemaker, a spectacle-clad monarch who rules over his seedy kingdom with ruthless omnipotence. (Yes, we nebbish story analysts like to dream of a world where the whims of wordy gatekeepers are king… we all have our fantasies). The symbiotic relationship between a press agent and columnist may be arcane today, but the sadomasochistic interplay is the same playing out in every corner of the corporate world: boss and lackey, top-dog and hungry striver, host and parasite. Here’s a fun way to pass the time: Divide your colleagues into the Falcos and the Hunseckers. (A tip: Anyone who thinks himself a Hunsecker is most definitely a Falco.)

Together, Hunsecker and Falco’s shared capacity for cruelty is a vernacular unto itself. Words are the trade, currency and weapons of choice in this putrid universe. Language is not merely language here: It’s a thieves’ cant, an acid-laced jargon meant to dominate others into submission. It is also the thing that separates Hunsecker and Falco from the rest of the world, tying them together as members of the same species. To speak fluently in the stylized argot of this rarefied group is to ascend to significance, to become a real person. Everyone else is merely matter.

As a teenager, I fantasized about becoming one of those hyper-articulate monsters — a cleverer version of myself with a sharp quip readily at hand, the kind of person who never started a sentence without knowing how to end it. With age came a new understanding of my favorite film: For all of Falco and Hunsecker’s poetic putdowns and velvet-clad threats, neither man has any real idea how to communicate with people. In a world where “integrity” is a dirty word and authenticity is considered fatal, both men are trapped in a childish game of cruelty and dependence. There is no real substance to their speech: It is the hollow language of hollow men.

Since working as a story analyst, I’ve come to appreciate writers with an acute ear for the awkward nuances of speech. We rarely say what we mean, and even when we do, it is usually inelegant and imperfect. There is still a music to it, among those stumbling tangents and verbal tics. Perhaps it’s not the polished jazz of “Sweet Smell of Success,” but the distinct colors and odd rhythms of our verbal failings make symphonies of even the most mutilated speech. I should know: The proof is on my tape recorder.

Presley Balholm is a story analyst specializing in book adaptations for Netflix and AMC. She can be reached at presleybalholm@gmail.com.