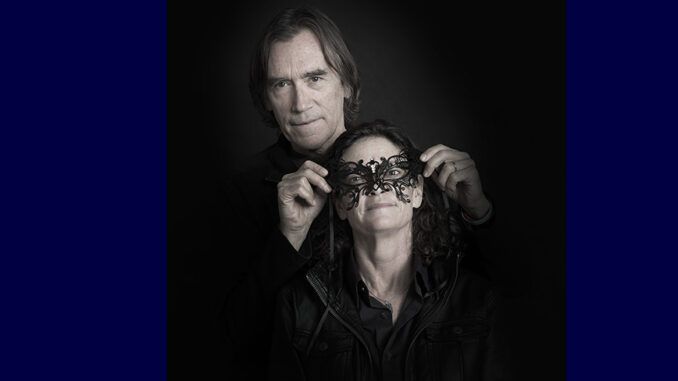

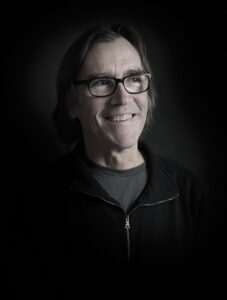

by Michael Goldman • portraits by Martin Cohen

Listening to singer-songwriter Halsey’s new single, “Not Afraid Anymore,” as it pulsates through a fresh Dolby Atmos mix on a stage at Universal Studios in the company of music editors Angie Rubin, MPSE, and Bill Abbott can be a bit of an unsettling experience. The track is accompanying an erotic sequence, known as the “Red Room” scene, in the new Universal Pictures film, Fifty Shades Darker, which opened February 10. Rubin and Abbott, after all, played key roles in helping to select and edit the song — and all the others in this sequel to the 2015 adult drama Fifty Shades of Grey, for which they also served as co-music editors.

The music sounds great, particularly on an expertly calibrated mixing stage. On the other hand, there’s a lot of, let’s say, “adult activity” playing out on the screen while the audio experience unfolds — not exactly the type of demo the two industry veterans typically offer visiting reporters.

Universal Pictures

“Concentrate on the music,” Rubin advises in a hushed tone.

Later, in Rubin’s office, the duo reminisce about their musical journey on the first two installments in the trilogy of films based on the best-selling book series written by author E.L. James. They have just wrapped their work on Fifty Shades Darker, in collaboration with director James Foley, music supervisor Dana Sano and composer Danny Elfman, and will shortly be segueing into the final film, Fifty Shades Freed, which was shot simultaneously with Darker and is slated for a 2018 release.

They both wish to emphasize that while the Fifty Shades movies are decidedly adult in nature, certainly not everyone’s cup of tea, and controversial in some quarters, the need “to showcase a lot of music — big, soaring music” in their soundtracks, as Rubin puts it, became exponentially more important as a result. Indeed, the first movie’s soundtrack went on to become the seventh-best-selling album of 2015, and two songs on it won major award nominations: an Oscar nomination for The Weeknd’s “Earned It” and a Golden Globe nomination for Ellie Goulding’s “Love Me Like You Do,” produced by Max Martin.

Abbott was the original primary music editor on the first film, which was directed by Sam Taylor-Johnson, before Rubin joined the project when it became necessary to re-do the score for a whole new cut of the film. The project’s musical requirements became so important at that point that Rubin was called by Rachel Levy, Universal’s senior vice president of film music, after completing her previous gig and asked if she could fly to London and join Abbott — with exactly a single day’s notice. Around that time, Abbott recalls mission statements from studio executives about the necessity of “delivering music worthy of a big cinematic event.”

“It was lofty thinking,” he recalls. “I remember, a couple months after we spotted the first film, it became clear that music, especially songs, would play a giant role, and they had to soar and be special. The songs had to be important, and they turned out to be, as the soundtrack’s success and the award nominations illustrated. And that mission statement has stayed the same.”

If anything, that mission grew in importance because the musical success of the first film’s soundtrack meant that any hesitation that some artists might have had about participating, given the sexual nature of the product, had melted away. Thus, by the time Fifty Shades Darker came around, “the amount of material that came in was amazing — thousands of songs, literally,” according to Rubin. “It has only just now stopped because we have told people we are finally print mastering. But we had buckets of material every day to sort through.”

Abbott adds that “the basic arc” of their process largely revolved around “the first half of [the project] being about trying to get a feel for what type of music was working, and the last half about getting down to the nuts and bolts, locking into the right song — many of which were written for the film — working closely with our picture editor [Richard Francis-Bruce, ACE] to get it all working right and, of course, our bosses making deals with artists.”

Additionally, the music editors had a lot of masters to please, no pun intended. Beyond the filmmakers and studio executives, particularly Mike Knobloch, Universal’s president of film music and publishing, they had to serve the needs of the rabid fans of the franchise, who were intimately familiar with James’ books — and with James herself — and the many specific musical references she wrote into her books, some of which she lobbied hard for during production of the movies. Then, of course, they had to make sure the performers they employed over the course of both movies were satisfied with the way they were cutting and utilizing their songs, including stars like Beyoncé, Annie Lennox, The Weeknd, Sia and Ellie Goulding, as well as Halsey, Taylor Swift and Zayn in the new movie, among others, who collaborated on the recently released single, “I Don’t Want to Live Forever.”

In other words, it was a big job compared to standard gigs; most movies these days typically use one music editor. But Abbott says that music became such an overwhelmingly important element in Darker — be it songs, underscore, featured songs, ambient or background music — that “almost every minute of the film has some kind of music in it.” The project’s huge musical needs thus demanded two music editors, leading, Rubin says, to a collaboration between herself and Abbott that allowed them to “partner up and make the songs and score fit and flow seamlessly.” Instead of feeling overwhelmed about managing the music of a billion-dollar franchise, they were able to help ensure that these movies “became a musical treat.”

Universal Pictures

Rubin adds that, for a lengthy period, she listened to approximately 20 to 30 songs a day — and sometimes two or three times that many — while sorting through reams of submissions from acts large and small. Her job was to help find, structure and incorporate the songs, while Abbott primarily concentrated on working directly with Elfman as he composed original material for the underscore.

Then the two of them together created bridges and hand-offs between various musical elements while extending or enhancing certain cues. Fifty Shades Darker finished with 64 music cues, representing about an hour and 51 minutes of music in the film, the editors say, including 28 original or found songs, featured or played as source music, and 35 pieces of original music written by Elfman as underscore.

Thus, although these movies obviously are geared to an adult audience, Rubin says she and Abbott felt the combined project represented “a higher calling” for them, and Abbott emphasizes that the project differed from their typical work because of the “sheer quantity of music required and the nature of the film.”

Having plenty of material to work with and lots of studio hands weighing in on possible choices, Rubin and Abbott sometimes found themselves experimenting to figure out particular sequences. This could occasionally get laborious, but it was also educational, they say, because the myriad of elements available to them — coupled with their skill, the talent of Elfman and their other colleagues, and the magic of their Pro Tools systems — allowed them to definitively prove or disprove a wide range of theories and possibilities, leaving everyone involved comfortable with their eventual final selections.

“We would get studio notes saying we should add a score cue here or there,” Abbott explains. “So Angie or I would temp something in, and if the powers that be liked it, it went on Danny’s to-do list. Quite a few score cues were added late in the process, but several ideas were broomed once everyone saw how the scenes played with music, including a nine-minute cue that played over a series of dialogue scenes. Danny was relieved to see that our valiant effort to temp that scene failed in the end. Instead, source music was used to help propel the scene, and when score did come in, it was much more emotionally effective.”

Universal Pictures

Rubin adds that among her many challenges was matching up songs with sexually charged moments without taking the easy or obvious way out — preferring, instead, for a subtler approach to making a proper match.

“A highly romantic or sexy song didn’t always work for those scenes,” she reveals. “We wanted to be captivating, but not always too on the nose. We didn’t want to add too much to what was already going on on the screen. We were already getting sexual intensity from the imagery, so we wanted to get something else from the song.”

Rubin remembers looking for a song for a scene in which Christian Grey (Jamie Dornan) introduces Anastasia Steele (Dakota Johnson) to a new sexual experience. “The temp was a Weeknd song at the time, but we knew we had to replace it,” she continues. “For these big-screen moments, we wanted original tracks written especially for the film. And then, the song ‘Pray’ [by the band JRY] arrived. I knew it was the one and ran with it. That song set the mood but wasn’t over the top or hitting you over the head with narrative lyrics. It had an interesting groove and a male vocal, since a male is, well, dominating in the scene. It wasn’t something I could explain, but it is the kind of thing a music editor thinks about — the kind of thing that people don’t realize we do in our work.”

She points to a similar development with what filmmakers called the “Elevator” scene, in which a sexual encounter takes place in an elevator — a fan favorite for readers of the books. Rubin says the scene was temped with Rihanna’s “Work,” which she calls “a playful, sexy, titillating production.” But the music editors knew they were not going to stay with that. “Hundreds of songs came in that were generally sexy or playful — all sorts of new songs,” she admits. “But, in the end, we went with a classic: Van Morrison’s ‘Moondance.’ You just never know where a scene is going to wind up.”

Over the course of the first two movies, Rubin and Abbott say they typically managed and organized vast quantities of songs and data themselves in Pro Tools 12.5.2, only adding an assistant — Denise Okimoto — late in the process on Darker. “We had to do most of it ourselves; we knew each song, where each body was buried, intimately,” Rubin explains. “It would have been tough for someone else to organize all that for us.”

“We were both working in Super Sessions in Pro Tools, which means we both had one big session going at all times,” Abbott adds. “So whether it was temp music, Danny’s demos or original songs, whatever was current was on top, but everything else was always there. In that sense, Pro Tools almost manages itself.”

In fact, the pair stresses that their infrastructure was somewhat low-tech on purpose, for security reasons anyway, with the music editors, sound editors, picture editors and other principals typically within walking distance of each other’s workstation at Universal’s post-production facilities. Therefore, Rubin jokes that rather than worrying about fancy networking and remote collaboration techniques, she and Abbott relied on the old “Sneaker-Net” approach.

“There was lots of security, and great file-transfer tools, and we used the PIX [remote collaboration dailies system] to share with [executives and others who were not on site],” she says. “But mostly, people would bring us drives if they had to; I call it ‘Sneaker-Net’ because we would just walk room to room to watch something and talk about it, the old-fashioned way. I think we benefitted from that; it is the easiest and quickest way to be creative and make decisions, compared to sending files back and forth.”

And so, in dealing with picture editor Francis-Bruce, his assistant Jennifer Spenelli, supervising sound editors Dane Davis, MPSE, and Stephanie Flack, MPSE, re-recording mixers Jon Taylor, CAS, and Frank Montaño, or anyone else, the music editors say their collaboration was an easy one. Indeed, their biggest issue was creative, not technical, revolving around regular, but gentle, push-pulls over how to properly balance the needs of the film narrative and the requirements of the artists who were contributing songs.

“There can be whole scenes that go in, come out, go in, come out, which is obviously tricky for our plans for a song,” Abbott explains. “There were times when we were really proud of transitions we did from score to song or song to score, and then, it turns out we scored to a song that no longer is in the movie; it got replaced. That’s just how it works, so you jump on your Pro Tools and look for a solution.”

Rubin notes that other types of challenges required innovative solutions as well. “A similar puzzle in both films were the main title songs,” she says. “Once again, wanting to honor many masters, we decided on another ‘Easter egg’ from the book series — either an artist or a song that was mentioned in the book. In the first film, we got the amazing Annie Lennox to cover Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’ ‘I Put a Spell on You’, and in Darker, we got Corinne Bailey Rae to cover Coldplay’s ‘The Scientist.’ Neither were easy feats.”

Abbott continues, “This is where Angie and I got to work creatively, hand-in-hand, with the blessings of the filmmakers, the artists and the studio. We got to structure the songs in both cases, and have Danny add orchestra for even more cinematic flourishes, while Richard worked with us to make sure everything hit where it needed to — sometimes adding, sometimes losing seconds of picture. It truly was a team effort in every sense of the term.”

Both editors repeatedly emphasized that sense of team, or “family” as Rubin put it, when talking about the musical achievements of the first two Fifty Shades movies.

“This is definitely not a family film,” Rubin chuckles. “But I think the team that made the movie really is a great family. In fact, getting to work with Bill kind of reminded me of the old days of the Gershwins — one writes the music and one writes the lyrics. Not that we did that literally; we are music editors. But we are that kind of a team, and that felt really good.” f