by Kevin Lewis

One of the vilest anti-heroes ever depicted in American films was the title character of Hud (1963), which was released 50 years ago in May. Amoral Texas cattle rancher Hud Bannon attempted to sell off his hoof-and-mouth diseased herd imported from Mexico before the state health inspector, who was contacted by Hud’s patriarchal father, ordered them shot. Hud’s relentless insults caused the old man’s death.

Hud was probably the inspiration for J.R. Ewing of Dallas TV fame. The rancher’s lack of ethics about the environment and the food supply, coupled with his “me first” mentality, is sadly still not unique today. His amorality, like his diseased cattle, has “gone viral” and is a contemporary metaphor for government and business ethics in food production, livestock, insider trading, mortgage lending and junk-bond trading. Every day there is a scandal about food derived from sick livestock being passed off to the public.

Paul Newman was already an icon when he portrayed Hud. Newman made a career playing heels, shady studs and emotionally conflicted men, perhaps the first (even before Marlon Brando) to achieve top 10 box office stardom in that style. Without his participation, it is doubtful Hud would have been produced; the book by native Texan Larry McMurtry, Horseman, Pass By (1961) was a bleak, downbeat story, much more harsh than the film version. The title is derived from the W.B. Yeats’ self-penned epitaph: “Cast a cold eye, on life, on death, horseman, pass by.”

The film turned out to be a hit, winning three Academy Awards (although Newman lost best actor to Sidney Poitier’s historic win for Lilies of the Field), and began the now half-century love affair Hollywood has had with McMurtry. Besides Hud, his novels were adapted into Oscar-winning films and Emmy-winning miniseries, including The Last Picture Show (1971), Terms of Endearment (1983) and Lonesome Dove (1983). The novelist himself won an Oscar for his screenplay for Brokeback Mountain (2004), adapted from the Annie Dillard short story.

Frank Bracht’s editing was distinguished, especially the unforgettable scene of the mass shooting of the diseased cattle.

Hud’s director Martin Ritt, who was friends with Newman, was a socially conscious filmmaker who had been blacklisted for a short time by the industry during the House Un-American Activities Committee era. Many of his films, from Edge of the City(1957) through Norma Rae (1979), focused on the plight of wage earners in dead-end jobs.

The film represented a comeback for two notable film stars from the Golden Age of Hollywood: Melvyn Douglas and Patricia Neal. Douglas, who played the old patriarch Homer Bannon, had been one of Hollywood’s most illustrious, light-comedy actors and a three-time star for Ernst Lubitsch, but had left the film industry because of his personal disgust with Hollywood and the Blacklist. He became a distinguished Tony Award-winning Broadway actor (The Best Man, 1960). Film audiences were astonished at this fine character actor’s transformation into a profound old man in Hud, for which he easily won the Best Supporting Actor Oscar.

Neal portrayed the worn-down housekeeper Alma, for which she won the New York Film Critics Award and the Academy Award as Best Actress. She had been blackballed by Hollywood for a different reason: Her public love affair with married Gary Cooper — after they starred in The Fountainhead (1949) together — divided the film industry loyal to the socialite Veronica Cooper. Neal had only one hit film in the early 1950s, The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), before she, like Douglas, returned to the stage. She was not an active part of the film industry in the late 1950s, except for her co-starring role with Andy Griffith in Elia Kazan’s critically acclaimed film A Face in the Crowd (1957) and a feature role in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961).

Why Neal was selected by Ritt is not clear. She was only 36 at the time but appeared older and weathered, the qualities needed for the beaten-down Alma, who was Halmea, the African-American cook, in the novel. It would be a stretch to posit that Ritt selected Neal for Alma because of her identification with the Ayn Rand heroine Dominique in The Fountainhead; Hud is certainly the demonic personification of the Rand ethos of un-trampled business. And it can be interpreted as the ultimate debunking of the Rand philosophy of self-interest and motivation over the needs for society’s economic stability.

Hud’s lack of ethics about the environment and the food supply is sadly still not unique today.

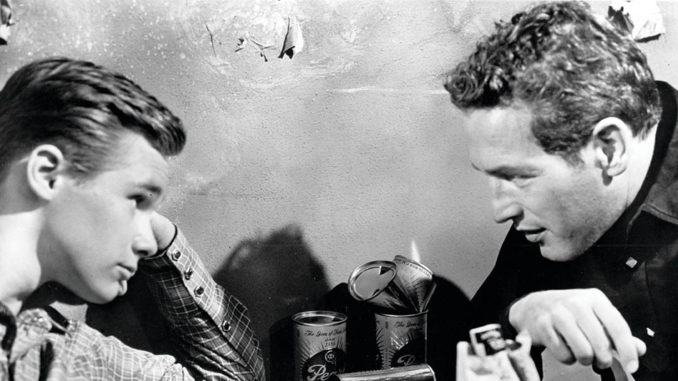

The casting of Brandon de Wilde as Lonnie Bannon, the hero-worshiping nephew of Hud, also evokes ethos of another classic Western, Shane (1953), for which he was Oscar-nominated as a child who similarly is inspired by the cowboy Shane (Alan Ladd). In Hud, Lonnie rescues Alma from the rape by his uncle and leaves Hud alone in the ranch. The young man is cured of his illusions, realizing that Hud was responsible for the death of his own brother, Lonnie’s father, in a drunken car crash.

Frank Bracht, who was nominated for an American Cinema Editors’ ACE Award for his editing of Hud, was an odd choice for the assignment. The editor, who died in 1985, had a long career cutting musicals (White Christmas, 1954; Funny Face, 1957; Damn Yankees, 1958), comedies and adaptations of Neil Simon comedies (The Odd Couple, 1968, his only Oscar nomination; Plaza Suite, 1970), but rarely dramas — the most notable being The Molly Maguires (1970).

However, his editing was distinguished, especially the unforgettable scene of the mass shooting of the diseased cattle and the attempted rape of Alma by Hud. The sensitive and creative editing of the attack was suggestive and shocking, rather than brazen, because of Bracht’s hair-trigger cutting in the Production Code era.

Hud was shot in black-and-white, which made the desolate Texas plains look more desperate. James Wong Howe won a richly deserved Oscar for his expressive cinematography. The land itself and the big sky became narrative characters.

There are no shortage of Huds in high places in our society today — corporate, banking and government — who despoil the environment, pollute for profit and deny global warming. In recent years, there have been many cases of tainted meal recalls, hog slaughterhouses polluting rivers and salmonella outbreaks. The water supply is threatened by fracking. Fifty years later, Hud emerges as a cautionary tale of what we continue to lose.