by Mel Lambert • portrait by Martin Cohen

In the time-crunched world of motion picture post-production, necessity is often the mother of invention. It is common practice for sound editors and designers to pre-dub complex effects sequences in their 5.1-capable edit suites when the goal is to produce a full-blown Dolby Atmos soundtrack in weeks rather than months.

However, supervising sound editor Lon Bender, MPSE, knew that he needed to leverage his many years of experience to develop a time-conscious workflow for director Kaige Chen’s IMAX 3DChinese martial arts offering Monk Comes Down the Mountain, which was shot entirely in China in the Chinese language, from Sony Pictures. Visual effects were created in Australia, while dialogue, ADR and background Foley were done by the Beijing-based team. But sound editorial and principal Foley were handled at LA’s Formosa Group, with re-recording — which started in early May — taking place at Audio Head in Hollywood. The film was released in Mainland China and Australia in July on no less than 12,600 screens, several hundred of which were Atmos-capable. At press time, there was no US release date scheduled.

“Monk was presented to me by the film’s editor, Wayne Wahrman, who advised me that Kaige Chen was looking to elevate the soundtrack to the Hollywood standard of creativity and detail,” Bender says, by way of explaining how the project came to Formosa. “After meeting Kaige, it was clear to me that he was very detail-oriented and would always ask, ‘What would we hear here?’ Upon discovering all the things we would hear, I was convinced that we needed the best man in town for the effects mix, which was Doug Hemphill.”

“I quickly realized I needed to apply some science to the project,” continues Bender, who started to block out a viable post schedule for his first Atmos soundtrack. “First, we needed to provide top-quality creative prep and mix organization for an epic film that had a limited budget. While we had many months to develop all the sound for the visual effects, environments and action sounds, the mix was quite truncated for a film like this. We went to extraordinary lengths to get the ‘sound’ of the film leading up to the mix in order to fulfill creative and budgetary goals. And secondly, we had to develop a solution that would allow the post team to use Dolby Atmos as a creative tool, without impeding the process. If Pro Tools panning and automated bussing could be utilized for access to the Atmos system, then we’d have a chance to be successful!”

Aside from seasoned veteran mixer Hemphill, CAS, who oversaw effects re-recording on Audio Head Stage B’s Avid ICON D-Control console, his mixing partner Joe Barnett handled dialogue and music, and Jared Marshack served as mix technician. Sound designer on the project was Kris Fenske, with Matt Wilson handling sound effects editing for the fight sequences and Bill Dean the complex atmospheres.

In essence, the supervising sound editor’s strategy for the Native Atmos soundtrack was to pre-mix in Atmos all of the sound design, effects, backgrounds and Foley effects in advance of the Stage B pre-dubs, which were limited to just six days. “With budgets decreasing, we needed to figure out a way to make Atmos work in the most expedient fashion possible, and concentrate on creativity and not on logistics,” Hemphill concedes. “Lon eliminated a huge amount of pre-dub time on Stage B because he did that work in his room.” Bender confirms: “That was the result of 195 hours of pre-mixing here in my editorial suite.”

With a track record of responding to workflow issues with solutions that use technology in the service of creativity, Bender is no stranger to invention. In 1994, he received an Academy Award for Scientific and Technical Achievement for development of the Advanced Data Encoding System, a technology designed to bridge the gap between linear film editing and non-linear sound editing using time code. The Digital Foley System, conceived by Bender in 2002, accepts input from the Foley artist as MIDI signals from pressure-sensitive foot controllers that trigger an extensive sound library of shoe types, surfaces and performances.

“Since all sounds stay where they were originally placed in specific food groups of sounds— including, for example, car chases, engines, skids, tires and scrapes — we can maintain VCA volume control over sounds going to the Atmos Field with unlimited simultaneous region selection” – Lon Bender

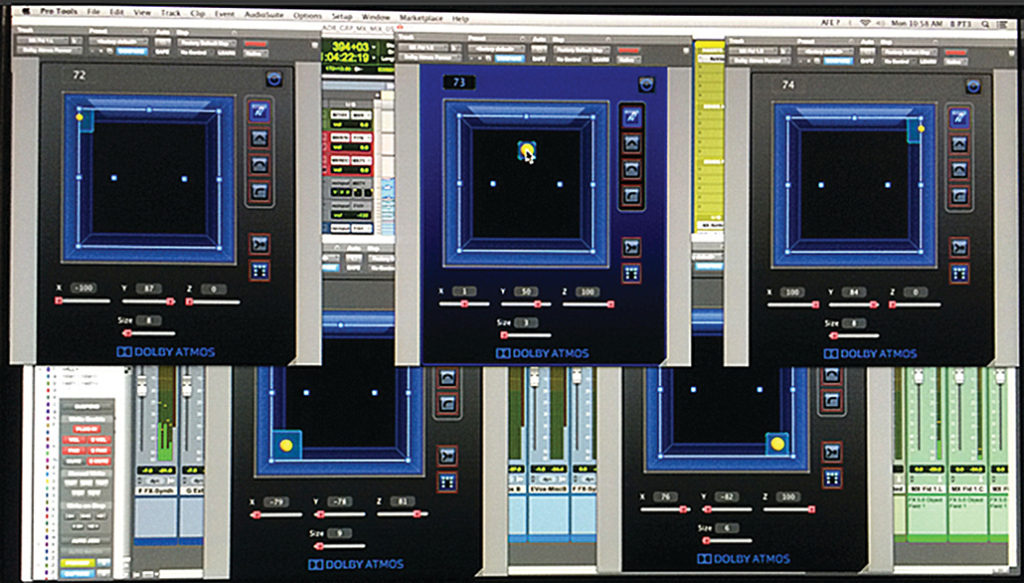

Dolby-certified for editorial and pre-production of Atmos soundtracks, Bender’s editorial suite at Formosa features an Avid ICON D-Command control surface and Pro Tools HDX with Atmos plug-in panners linking to a local renderer — another Pro Tools plug-in that emulates a Dolby Atmos Rendering Mastering Unit/RMU— and hence to a 9.1.4-channel loudspeaker array. The latter is a horizontal 9.1-format setup with four overhead speakers, all individually addressable from the local renderer. By writing assignment and pan automation with his Avid Pro Tools mixes, Bender could bring that data to the dub stage within his multi-channel sessions.

“Everything is such a rush when you get onto the stage,” he explains. “Without that pressure I have contemplative time here in my Atmos-capable room to work out panning and moves through 3D space, and an approach on how to make that access virtually transparent” without the clock running.

MOVING SOUND IN THREE DIMENSIONS

“I had researched other approaches to Atmos mixing, which utilize object tracks either at the bottom of the session or within our ‘food groups,’” Bender explains. “I imagined Atmos Fields whose profile I could control, and into which panned sounds can be placed. We used the Atmos Panners very little for panning, although access would be needed from the discrete tracks within each food group — whooshes, impacts, flying, etc. — to hasten the process.”

As a result of his investigations, Bender made a number of significant breakthroughs. “I conceived Atmos to be a tool that would let me create a sonic ‘plane’ in three dimensions, through which targeted sounds would move,” he continues. “I set each Atmos Panner at a static point and used them as way points to identify the ‘shape’ of the Atmos Field using the X [left-right], Y [front-rear] and Z [height] coordinates. I could then develop various Atmos Field Profiles — directions through which sound moved, according to the waypoints I had created — that were specific for sound effects, design, backgrounds and music. An examination of these shapes proved that different Field Profiles provide different experiences.”

Unlike hardware-based digital consoles such as Neve DFC Gemini and the Harrison MPC Series, on which on-surface panners and joysticks can be used to develop routing and pan automation data for the Atmos 9.1-channel bed and up to 118 discrete mono/stereo objects, the Avid ICON available to Bender only enables pan data to be derived from the console’s joysticks controlling the Atmos plug-in, which then sends data to the RMU. Automation of output routing currently is not supported, although it can be conformed in editorial, along with the audio. (See sidebar on page 45 for additional information.)

“Despite the lack of automated buss routing on our ICON consoles, I realized that I could use the send busses instead of the auxiliary outputs to send the pan data to the Atmos Fields, a technique that offered several operational advantages,” Bender says. “In addition to providing simple access to unlimited regions to the Atmos Fields, it carries Pro Tools panning developed during editorial to the re-recording stage, ‘fooling’ Pro Tools through the use of dummy output busses. It also provides dynamic bussing to the Atmos bed, object fields and panners using just six send busses, which utilize Pro Tool’s Follow Main Pan/FMP settings to allow the panning to move sounds through the Atmos Fields, and hence eliminates the need for dedicated Atmos Tracks.”

Bender used color-coding in existing tracks to identify regions being directed to Atmos Fields: Blue for Everything and Green for Atmos beds and objects. “Since all sounds stay where they were originally placed in specific food groups of sounds— including, for example, car chases, engines, skids, tires and scrapes — we can maintain VCA volume control over sounds going to the Atmos Field with unlimited simultaneous region selection while sending sound elements to the Atmos renderer, and can use Pro Tools panners for all our pans, even in Atmos,” he adds. In the accompanying illustrations of sample sound effects, design and backgrounds Atmos Fields, the numbers represent X-Y-Z coordinates and object size of each waypoint. “The different Field shapes are applicable to the particular effect being used on a specific film,” Bender explains. “The layouts represent Atmos objects as waypoints in space that creates the required 3D motion; sounds are then blown through the field from their original track position using Pro Tools panning.

“The Atmos Field Profiles include numbers in circles that represent, following the Dolby Atmos nomenclature, Axis Z or height. Numbers to the right represent the object’s size, which is also represented by a Square that signifies 3D Divergence,” he continues. “Beyond normal divergence, which moves a signal away from the source point along a single horizontal plain, 3D Divergence expands the signal in every direction equally away from a source point. A box with a source point in the center would represent this manner of divergence and would soften the point-source quality of a location within the movie theatre. Numbers above the box represent the X left-right axis and Y front-back axis.”

According to the sound editor, when sound effects or music elements are assigned to these field profiles, complete with Pro Tools pan data, they move in these pre-programmed directions, either on a horizontal plane, or with height — for example, low center, low front sides and high rear — and other combinations. “I also favored the idea of accessing the sounds in food groups that editors are working in,” he adds. “To leave everything where it is and then dynamically access them through our Atmos Fields seemed a perfect way to simplify the process.”

REASSIGNING TARGETED SOUNDS

Bender then needed to develop a simple technique to reassign targeted sounds from the Atmos 9.1 bed into Atmos objects that can be moved through space using Atmos Field profiles. “I would normally use auxiliary busses,” he explains. “But in Pro Tools, you cannot program them to go on and off; I needed to get to the different Fields dynamically. I achieved this by using the send busses, because you can automate on/off data; in essence, you need a multi-channel output to make an automated pan work. So I used sends to turn on and off the bed or object assignment instead of an aux. That dummy aux concept and the use of sends to turn on/off assignments was the key.

“All of a sudden I wasn’t using the Atmos panners to move a sound,” Bender continues, “but rather to develop a waypoint in space. I could then use the Pro Tools panning developed by myself and my sound editors to move sounds within an Atmos Field that we could access at will using the dynamic bussing via sends instead of aux outputs. I can take mono, stereo or left-center-right elements into multiple speaker pairs anywhere in the Atmos soundfield, with a variable object size or divergence, dependent upon our needs.”

Mixer Hemphill adds, ‘I simply highlighted the Pro Tools tracks, turned off the pipeline to the bed, and then turned on one that is going to the Objects via the pre-designed Atmos Fields,” I could then send to different outputs but still honor pre- designated pans. I was lucky to find that Pro Tools offers that functionality via sends: designated FMP-Follow Main Pan. To move multiple tracks into Atmos Objects just takes a simple copy-and-paste sequence and a couple of button clicks; it’s remarkably fast and elegant, taking just several seconds.”

“I’m not pretending to do Doug’s job,” Bender explains. “I’m just leveling things and getting them to sound the way I want. Then a talented re-recording mixer like Doug takes them to the next level and does his magic on them.” Hemphill agrees, saying, “Changing the object size softens the location of a pan to create a far smoother pan because of the broadened divergence. Pro Tools panners work in a 5.1-channel horizontal plain, but now we can put an effect into one of Lon’s three-dimensional Atmos Fields and that takes it up into the height plane” because of the trajectory through the pre-assigned waypoints.

“While we had many months to develop all the sound for the visual effects, environments and action sounds, the mix was quite truncated for a film like this. We went to extraordinary lengths to get the ‘sound’ of the film leading up to the mix in order to fulfill creative and budgetary goals.” – Lon Bender

Bender cites his BG1 Atmos Field as an example. “That isn’t designed to pan sound around the room, but to send sound through some locations with the Pro Tools pan data already written onto it. The Field is a pre-defined trajectory with the original pans and volume setting retained from sound design. It is not written as an Atmos panner but rather a Field with waypoints that carry over the automated Pro Tools panning for the duration of the track. Now, any sound rendered through BG1 will have that shape trajectory through the 3D immersive soundfield.”

“Because of the speed and the ease of incorporating his automated moves, the creative possibility of what Lon has done is enormous,” explains Hemphill. “Those pre-programmed fields were carried right through the project; I might have moved to a different field shape but never modified his moves. Whether I put Atmos sound elements into the bed or treated them as objects depended upon what we wanted to achieve in the final soundtrack. Lon has come up with a very simple sequence for what is normally a very complex sequence of events.”

“In addition to the static 9.1 bed, Atmos offers 118 objects; normally you take the next one available,” Bender adds. “But I wanted to pre-organize these objects in advance of the mix. I delivered an 83-track Object Stem — 1 thru 21 were Objects we will use for effects, then Foley, then backgrounds and so on — using waypoints to make a profile. They were in groups of five because I used 5.0-channel ss and panning; Pro Tools also supports 7.1-channel sends if I wanted additional ways to generate more complex shapes. But that would have used up more objects.”

“The workflow during a mix is like being a kid in a candy store; I can do whatever I want,” Hemphill says. “I can use 7.1; I can do this; I can do that; I can use Atmos — and it’s all very fast. Lon and I were always on the same page with Joe Barnett and Jared Marshack, the mix tech, who played a huge part on the stage; he handled all of the Pro Tools assignments, and let me get on with being creative. Having a savvy mix tech on the stage is very, very important; it’s the new paradigm for mixing. With Pro Tools sessions of this size and complexity, you need somebody on the stage like Jared.”

Hopefully, Monk Comes Down the Mountain soon will receive an American release, so domestic audiences can see — and hear — what Bender and Hemphill are taking about.