Waves Passing in the Night:

Walter Murch in the Land of the Astrophysicists

by Lawrence Weschler

Bloomsbury, 2017

Hard Cover, 165 pages, $25.00

ISBN # 978-1-63286-718-6

by Betsy A. McLane

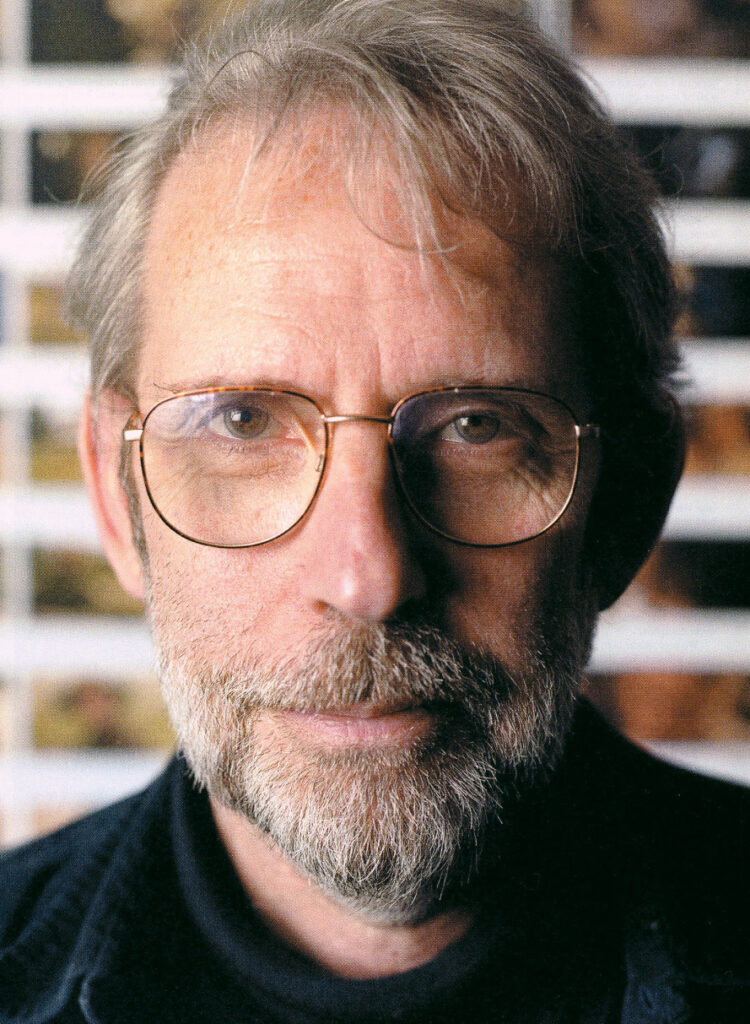

The title of Lawrence Weschler’s book, Waves Passing in the Night: Walter Murch in the Land of the Astrophysicists, is complex and slightly mysterious, fitting for an exploration into the mind of legendary picture editor, sound designer, sound editor, re-recording mixer, writer and director Walter Murch, ACE, CAS, MPSE. Murch has previously and generously expounded on his experiences, inspirations and techniques in the fields of sound recording and design, as well as picture editing, in two editions of his own classic book, In the Blink of an Eye: A Perspective on Film Editing (Silman-James Press, 1995, 2001). A part of the fascinating terrain of his thoughts on film was limned by Michael Ondaatje (author of the novel The English Patient, 1993) in The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film (Knopf, 2004). Weschler’s title portends that now it’s time for something completely different from Murch that may, or may not, be true.

For 50 years, Walter Murch has astonished moviemakers and audiences with aesthetic and technical innovations that fundamentally changed cinema sound. He clomped through the San Francisco Natural History Museum in self-made metal shoes at 2:00 a.m. to create police boots for THX-1138 (1971), then came up with his so-called “law of two-and-a-half” via those footsteps.

For 50 years, Walter Murch has astonished moviemakers and audiences with aesthetic and technical innovations that fundamentally changed cinema sound. He clomped through the San Francisco Natural History Museum in self-made metal shoes at 2:00 a.m. to create police boots for THX-1138 (1971), then came up with his so-called “law of two-and-a-half” via those footsteps.

His career-long partnership with director Francis Ford Coppola includes serving as supervising editor, sound designer, re-recording mixer and sound editor (the latter uncredited) for The Conversation (1974), and working in multiple post positions (including post-production consultant) among the films of The Godfather Trilogy (1972, 1974, 1990). Not to mention wrangling 1.25 million feet (236 hours) of workprint from the Apocalypse Now (1979) shoot (one of the biggest problems was moving that amount of film around on pallets!) as one of three credited picture editors, sound designer and re-recording mixer. More recently, his picture editing and re-recording mixing enhanced feature documentaries such as Particle Fever (2013). Throughout it all, Murch has never stopped experimenting.

He is the only film editor to receive Oscar nominations for editing films on four different systems — Julia (1977), upright Moviola; Apocalypse Now, Ghost (1990) and The Godfather, Part III, KEM; The English Patient (1996), Avid; and Cold Mountain (2003), Final Cut Pro 4 — and is the only person to win Academy Awards for Best Film Editing and Best Sound (mixing) for one film, The English Patient. All of this and much more about Murch is well-documented, due to his willingness to share insights into his craft and his remarkable ability to speak at length, entertainingly and with great erudition, about the complex ideas that spur his artistry.

Waves Passing in the Night moves beyond film, exploring another of Murch’s passions. As his biography states, “Between films, he pursues interests in the science of human perception, cosmology and the history of science. Since 1995, he has been working on a reinterpretation of the Titius-Bode Law of planetary spacing, based on data from the Voyager Probe, the Hubble telescope, and recent discoveries of exoplanets orbiting distant stars.”

Titius-Bode is a “rule,” advanced in the 18th century by German astronomer Johann E. Bode (1747-1826), but probably first formulated by a colleague, Johann D. Titius (Tietz) (1729-96). The theory attempts to explain the position of planets using a formula based on the series 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, 96, 192, 384 (after the number 3, simply double the preceding number), then adding four to each number and dividing by ten, which results in a very good approximation of the distance in astronomical units of the planets in our solar system from the sun. It is widely discredited by today’s astrophysicists as a mathematical coincidence, since there seems to be no physical explanation, and it fails to apply to the outermost planets in our solar system, although the recent and continuing discovery of hundreds of exoplanets is seen by some as an opportunity to reconsider Titius-Bode.

With text arranged in excerpts from mutual correspondence and conversation, along with parts of Murch’s TED talk PowerPoint presentation on the subject, Weschler does a good job — and Murch an even better one — of explaining Titius-Bode. That is only part of the fun found in this small book.

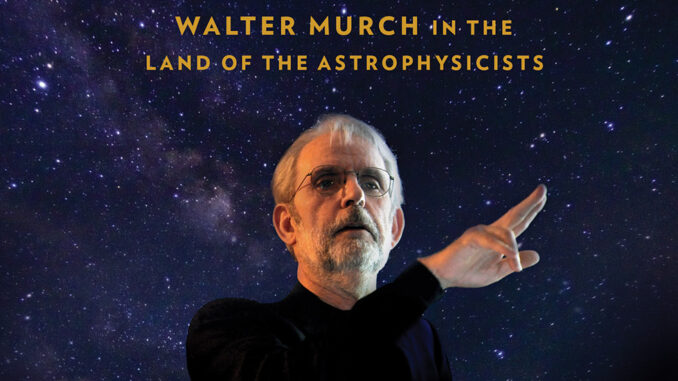

As an acoustician for whom thinking about sounds is as natural as breathing, Murch takes Titius-Bode a step beyond its hypothesis and relates it to musical waves. He demonstrates how the ratio between the distances of planet orbits predicted by Bode is the same as the ratio between the notes of the musical scale, and points out, “Mathematically, the Bode formula generates musical ratios, and insofar as the Bode formula describes the relative position of the solar system’s planets (and their moons), it also describes a musical configuration.” He describes music in space — not Pythagoras’ “Music of the Spheres” concept (although that too makes an appearance in the conversation), nor sounds produced by human machinations, but rather the result of the various vibrations every object creates when it is “struck, bowed, plucked or blown.” The book jacket emphasizes this puzzling relationship of music to planetary movement, showing a somewhat disembodied Murch emerging from a starry sky, seemingly conducting these planet waves.

Weschler, a prolific journalist and critic, was a staff writer for The New Yorker for more than 20 years and has authored several books, including Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder (Pantheon, 1995), which was short-listed for the Pulitzer Prize. His style is informed and engaging, occasionally a bit precious, but always respectful of his subject. Fans of The New Yorker articles will find much to enjoy in his writing. He allows the reader to approach the labyrinth of his subject’s mind through Murch’s own words, then adds dissections, counter-ideas, historical references and thoughtful interviews with established professional astrophysicists whose responses to Murch’s work range from scorn to skepticism to admiration.

Waves Passing in the Night thus becomes much more than a book about celestial mechanics or a book about Murch’s ideas. It raises, but does not answer, questions about the relationship of the “skilled amateur” who seeks truth in any discipline to the powers that be who decide what is acceptable evidence. As a jacket blurb from documentarian Errol Morris reads, “We come to see science as a closed club, science as abstruse and narrow, science as caste. But Weschler allows that it could be the other way around, too: Science as a protector of truth and progress, science as guardian against kooks.”

The author also questions his own positions, and allows many parties with skin in the game to have their say. John Cage, Michel Foucault, Arthur Koestler, Margaret Wertheim, Lee Smolin, Edgar Allen Poe and others appear along with such usual suspects of Einstein, Kepler, Newton, Lucas and Coppola. Photographs and historical portraits along with graphs, old and new, charmingly dot the pages of Waves Passing in the Night.

Reading it is akin to attending a wonderful party, hosted by Weschler, honoring Murch and inviting you to join in the fascinating conversation.