by Edward Landler

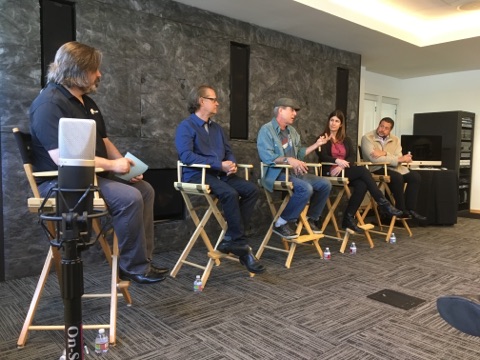

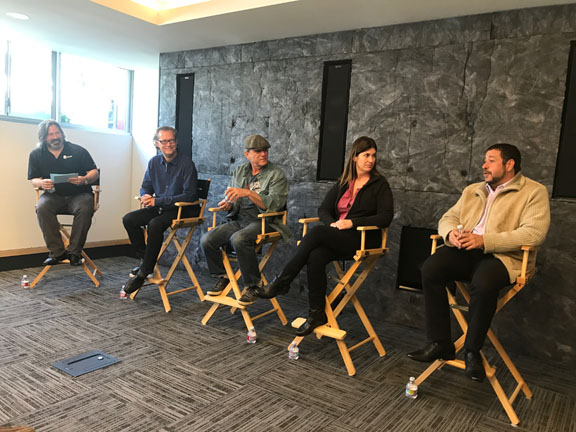

More than 40 people filled the Dede Allen Seminar Room at the Hollywood offices of the Motion Picture Editors Guild on Saturday morning, March 18 for the third installment of the four-part “Meet the Artists” discussion series. Exploring the different craft classifications represented by the Guild, the series has previously presented picture editors and Foley artists and the third hosted an impressive panel of television technical directors.

With a focus on handling the high pressure of editing live events as they happen, and contributing their own artistic and creative input to the shows, the panelists were:

Eric Becker, a winner of five Primetime Emmy Awards for his work on Grease Live! (2016), the 2015 Oscars, the 2012 Tony Awards, American Idol (2002-16) in 2011, and the 2008 Grammy Awards;

Charles Ciup, nominated for the Primetime Emmy 10 years in a row for Dancing with the Stars (2005-present) and winning four times (2008, 2010, 2014, 2016), recently technical director on Hairspray Live! (2016), and currently on Judge Judy (1996-present);

Lucinda Ireland, a two-time local Emmy winner for the LA Marathon and the Dodgers, with longterm credits on Wheel of Fortune (1983-present), Jeopardy (1984-present), The Bachelor (2002-present), Shark Tank (2009-present) and Tosh.O (2009-present); and

Robert LaMacchia, who has won Primetime Emmys for the Opening Ceremonies of both the 2008 Beijing Olympics and the 2006 Turin Winter Olympics, and is currently working on Let’s Make a Deal (2009-present).

Moderating the discussion was Paul Overacker, the technical director representative on the Editors Guild Board of Directors. Among his credits are NFL Total Access (2007-16) and Dr. Phil (2007-present); he was nominated for a Sports Emmy for his work on Super Bowl 50 (2016).

Opening the program, the moderator described the technical director as “an editor for live television production.” He continued, “We take in all sources, feed it into a switcher and take it out in a live cut; we key, cut and create effects.” Emphasizing the stress and the excitement of the job, he noted, “When you’re live on the air, you can’t fix it in post.”

The panelists followed sometimes similar paths into live TV work. Becker took a television class in seventh grade, one of two programs in the State of California at the time. He later became a musician, which led to work in sound studios and then to doing sound for TV. His first paid TV station job was in the tape vault.

Intending to be a disc jockey, Ciup enrolled in the Communications and Media program at Toronto’s Ryerson University but a TV production class showed him he could make a living “playing video games.” He stayed on at Ryerson, teaching TV production until he answered a call from the Canadian Broadcasting Company (CBC) seeking to hire promising graduates. He started as a switcher in Toronto and moved to Vancouver to work as a tech director and producer. Coming to LA, he first wrote for local TV news and then filled in as a switcher at Hollywood Center Studios.

At age 14, Ireland was a DJ at a Las Vegas radio station and, at 16, got a job at a local TV station and left school. She worked full time at the station and as a freelancer with TV sports, which occasionally brought her to Los Angeles. In 1996, she was asked to move to LA by National Mobile Television to work as a sports TD.

After high school, LaMacchia learned television at a two-year school and, he said, “I just loved switching.” His first job was in radio but he moved into working on TV news. On his own time, he would take the news announcer’s track and learn by creating the visual track for it. From there, he got into TV sports and eventually entertainment shows.

Getting into the meat of the session, Overacker asked his fellow TDs about the process of setting up their shows. Each of them had their own take on what they called the ESU — engineering set up — or, as Becker referred to it, “Everybody show up.”

Becker explained, “Typically, you get only one ESU day, sometimes more. That’s before the director and the producer walk in. By the end of the day, you make sure everything’s up and running: tapes, graphics machines, tally lights, communications…”

No matter what show he works on, Ciup said, “My set up is much the same. There’s a technical meeting well before the season starts and everybody talks about what they need; then we get ready for ESU day. For the live show, everything has to be there. As a switcher, as a technical director, you’re a live editor. You are the last point before the picture ends up in everybody’s living room.”

Even though they are posted, Ireland pointed out that shows like Jeopardy or Tosh.O are done live. “We’re basically switching the live show for the studio audience,” she said. “We have one day of ESU at the beginning of the season, but things are broken down from week to week, so every week we have to run through everything to make sure it all works. The whole monitor wall has to be ‘refaxed.’”

For a major athletic event like the Olympics, LaMacchia said, “We have 10 to 12 days for opening setup and rehearsal. The process is kind of slow and you can be put anywhere…it could be a truck. In Beijing, we were literally in a shed.”

Touching on the creative aspect of his job — making digital video effects (DVE) for Let’s Make a Deal, for example — he said, “They let me do whatever I want to do. We do all the graphics there, like digital snowfall; it’s all in the switcher. We have a day to set up for the next three weeks. The hardest part of that show is bringing in the right camera to the right door at the right time.”

With praise for Wheel of Fortune’s director, Bob Ennis (also a TD), Ireland said, “For graphics you may get an idea from a producer. ESU is like it’s all there, and the rest of the morning is making those kind of effects to show to an audience. The DVEs are all layered live.”

In response to a question from the audience about preparing people to replace or cover for the TD, she said, “I get six pages of notes from Bob and you pass on whatever data you can. A lot of shows will pay for an ‘observe’ day.”

For a scripted show like Hairspray, Ciup downplayed his creative leeway. “I spent 10 days head down getting my part right. I’m expected to be at a certain place at a certain beat.” For other kinds of shows with music, like awards ceremonies, Becker agreed. “It’s mostly execution, he added. “We’re not there to be very creative. Creatively, we try to push a little ahead, to be ahead of the beat. It’s all about nuance. For every cut that goes on the air, I use Preview to see ahead.”

In answer to Overacker’s query about how working with different directors changes their shows, all the panelists remarked on their close collaborative relationship. Becker said, “Directors are all different and a lot of it is having a good time and getting along with the people. You have to understand what the directors want and read their mind.”

Ciup continued: “Sometimes you get to the point where you understand what they want by the inflection in their voice.” He went on to describe when Dancing director Phil Heyes took over for the meticulous Alex Rudzinski, noting, “Phil works space the same way as Alex, but with a very different personality; it was a more free-flowing process.”

Ireland added, “It’s a real neat friendship thing, a cool team harmony. I tend to change my personality to what the directors’ are.”

The moderator asked what the key technical advances for TDs have been, and Ciup immediately responded, “Going from analog to digital — the single biggest innovation in our job. We used to work a week to set things up. Now, setting up takes a couple of hours at the beginning of the show and afterward, you walk in and, if you’ve set it up right, it’s all there.”

The new technology, though, has affected how TDs learn and prepare for their job. A trainer for Sony, Ireland said, “Now you’ve got to be pretty computer-savvy. I read manuals, but you’ve got to have the guts to tear the system apart.” Ciup continued, “On the very first Sony switchers, we had to figure out where the menus were. Sometimes you find things just by playing around.” LaMacchia summed it up: “You got to be willing to push buttons and suffer sometimes.”

Questioned for advice about starting out today, one of the other panelists recalled LaMacchia’s early TV news experience. Going into more detail, he said “You get a work flow that way without somebody breathing down your neck. Record a director’s track, play it back, work through the whole thing and try things out. Rhythm and timing is everything.” Ireland also noted, “You’d be surprised what you can learn online on videos and in manuals.”

An assistant editor in unscripted TV asked why there was “no definitive path for an assistant to get to be a tech director.” Ciup said, “You have to want to do it,and that’ll guide you. Find places where switching is being done all the time and gravitate to positions where you learn it. On TV news, you’ll be going through more things than we do on a regular basis. ”

Ireland suggested workplaces to learn switching, “Stadiums are fantastic…Dodger Stadium…Staples Center…even big churches have switchers.” Becker added, “There’s more to it than pushing buttons. The more you understand the process of TV production, the better TD you’ll be.”

A final question from the audience sparked a deeper discussion about the differences between the different kinds of live shows on which the panelists had worked. Ireland saw the change from working on sports to entertainment shows as a matter of politics: “Different rules and different jobs; who moves the camera is different and you talk to different people.”

LaMacchia observed, “Entertainment is much more precise. In sports, you’re coming and creating the event [on camera]; you have to have it set and be ready to go for it. You have to think it through yourself.” Ciup added, “In sports, we’re building the show as it goes along. You’re making half of what you make on the ‘shiny floor’ shows, and the ‘shiny floors’ are a lot easier.”

With the panel discussion ended, moderator Overacker invited the audience to the back of the seminar room to observe a demonstration of the DYVI, a new switcher developed by EVS, brought to the event by technical director David Bernstein. Bernstein said, “This is the new generation of switchers. Even if I work with this on every show I do from now on, I’ll never find all the things it can do.”

More than a dozen technical directors were in the audience for the “Meet the Artists” event, including such veterans as four-time Primetime Emmy winner Rick Edwards, current Ellen: The Ellen DeGeneres Show (2003-present) TD Zach Greenberg, and Jimmy Kimmel Live (2003-present) TD Ervin Hurd.

Hurd told CineMontage, “This is a great networking opportunity. To have a lot of TDs get together to share their expertise is exhilarating.” Remarking on the exhilaration of the fast-paced work itself, Conan (2010-present) TD Beth Stiller said, “The joy of the work came through, you really have to love it…and what a great variety of shows.”

The panelists, too, expressed what they got from the event. Ireland said, “It’s interesting how similarly we all see things — and we’re all pretty hyper and quick.” LaMacchia was grateful for the opportunity for “us to share so everybody understands what we do.”

The future was board member Overacker’s main concern. “Television is a changing industry,” he concluded. “Kids can now shoot and edit video on their iPhones. Most news stations are going fully automated. Who’s going to follow us as the new generation of technical directors?”