by Mel Lambert

Intricate sound design usually involves preparing effects and ambiences that create a realistic, immersive environment for a motion picture audience. In the case of writer/director Edgar Wright’s latest outing, the action drama Baby Driver, which opened June 28 through TriStar Pictures, his regular sound designer/supervising sound editor and re-recording mixer Julian Slater faced a far greater challenge.

The eponymous hero of Baby Driver, played by Ansel Elgort, is forced to work for a veteran kingpin in exchange for the start of a better life. But, as the result of a childhood accident, the young man suffers from aggressive tinnitus, which affects his concentration during day-to-day activities. To block out its effects while piloting a getaway car for a gang of scurrilous bank robbers — portrayed by a cast including Jamie Foxx, Kevin Spacey, Jon Hamm and Jon Bernthal — the lead character plays pop music at elevated levels in his ear buds. He now relies upon the beat of his preferred oldies soundtrack to remain the best in the crime world, with music heightening his driving focus and reflexes.

The film, which premiered at the South by Southwest Film Festival in Texas in March, follows the progress of the getaway driver who, after being coerced into working for a crime boss played by Spacey, finds himself taking part in a heist that’s doomed to fail.

British-born Wright is probably best known for his black comedies Shaun of the Dead (2004), Hot Fuzz (2007), Scott Pilgrim vs. the World (2010) and The World’s End (2013), all of which featured Slater’s talented sound work. In contrast, Baby Driver is the director’s first film to be shot in the US — principally in Atlanta — with possible creative influences from The Driver (1978), Raising Arizona (1987) and The Blues Brothers (1980).

Late last year, Slater handled music and sound effects pre-dubs at Goldcrest Films in the heart of London’s Soho film district, while British co-mixer Tim Cavagin worked on dialogue and Foley pre-mixes at Twickenham TWI Studios in Richmond, a suburb west of the UK capitol. Finals started just before Christmas 2016 at Goldcrest, with Slater handling music and sound effects, while Cavagin oversaw dialogue and Foley. “We used Goldcrest’s new Dolby Atmos-capable Theatre 1, which opened a year ago,” Slater recalls.

“Because of the lead character’s tinnitus, we worked with pitch changes to interweave various elements of the film’s soundtrack,” Slater says. The film is rumored to be partially based on a music video for British electronic duo Mint Royale and its track “Blue Song,” also directed by Wright. The video stars Noel Fielding as a music-loving getaway driver for a group of bank robbers, one of which is Wright’s regular, Nick Frost. Composer Steven Price’s score for Baby Driver was recorded at Abbey Road Studios in North London.

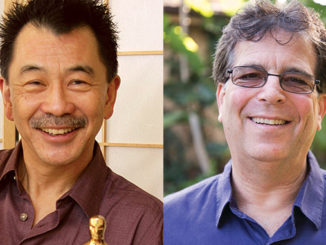

Also hailing originally from England, Slater is a multiple BAFTA and Emmy Award nominee who has worked with a variety of world-class directors. After graduating from the School of Audio Engineering (now SAE Institute) in London, at the age of 22 he co-founded the Hackenbacker Audio Post company and designed sound for his first feature film, director Mike Figgis’ Leaving Las Vegas (1995). Subsequent films included Shaun of the Dead, In Bruges (2008), Dark Shadows (2012), Scott Pilgrim Vs. the World and Attack the Block (2011). Slater relocated to the US three years ago, working first at Formosa Group and later at Technicolor at Paramount in Hollywood.

Integrated Music and Sound Design

“From its inception, this has been a movie for which music and sound design work together as a whole piece,” Slater explains. “There is a large amount of syncopation of the diegetic sounds to the music track that Baby [the lead character] is listening to; this is something that Edgar had in mind since he first developed his idea for the movie.” Diegetic sounds are implied to be present by the film’s action, such as characters’ voices or sounds made by objects.

“Sometimes it’s obvious because the action was filmed with that purpose in mind — for example, walking in tempo to the music track, or guns being fired in tempo,” the sound designer continues. “But many times it’s more subtle than that, including police sirens or trains in the distance that have been pitched and timed to the music, so that they blend into the overall musical journey we experience. We strived to always do this to support the story, and to never distract from it. Many times we tried to add something that worked with the music, but discovered that it didn’t work cinematically, and vice versa.”

How does Slater signal the hero’s tinnitus condition, without distracting the audience with fixed-frequency tones? “Whenever Baby is not listening to music, his tinnitus is present to some degree,” the sound designer explains. “It became apparent very soon in our design process that strident, high-pitched whistle tones would not work for a sustained period of time. Working closely with composer Steven Price, we developed a varied set of methods to convey the tinnitus; it’s rarely the same sound twice. Much of the time, the tinnitus is pitched according to either the outgoing or the incoming music track. This then enables us to use more of it, but be quite subtle at the same time.”

Slater says that Avid Pro Tools’ musical aspect was a key element in his design. “It’s funny that I have used Pro Tools day-in and day-out for the past 15 years, but never worked in Beats and Bars mode,” he concedes. “We tempo-mapped each piece of music so that we could then stretch and pitch each sound according to the tempo of the track at that particular moment. Some of the tracks varied in tempo quite significantly within themselves, which presented quite a challenge. Trying to keep a car alarm in tempo with a punk music track that is moving around in tempo meant that we had to find ways to briefly bury that sound in the mix, and then reset the tempo for the next cut where you would hear it again. All the time, we would make sure that the sounds work not only dramatically and cinematically, but also musically.”

The choice of the source music had started a decade earlier, Slater notes, with tracks from the Damned, the Commodores and other acts being selected by the director to punctuate his script. “To be honest, that very detailed template was a luxury,” the sound designer confesses. “Because all the tracks had been written into the script and cleared for use before the shoot; very little of it changed. From memory, only two pieces of music were altered during the entire post period, and that was due to Edgar’s choice. Obviously, large chunks of the design are hinged on the music tracks and, as such, knowing that these cues wouldn’t change meant we had full confidence to build the design around it.”

Slater was in regular, day-to-day communication with the composer or his music editor. “We were continually handing elements over to them so they could be incorporated into the score,” Slater says. “A good example of this is a scene with the gang after a gun deal has gone awry. Steven took a variety of diegetic sounds from me — clock ticks, bag drops and light switches — and wove them into his score. As the tension builds dramatically, these diegetic elements continue to build within the score, thereby creating a really interesting set piece, both dramatically and tonally.”

Native Dolby Atmos Immersive Mix

The soundtrack was mixed natively in Dolby Atmos. “All the source music was derived from stereo master mixes,” Slater recalls. “Essentially, I did a music pre-mix for all the source music and upmixed stereo to the 9.1 Atmos bed using a mixture of [Nugen Audio] Halo Upmix, [the Cargo Cult] Spanner, and FabFilter Pro R. Spatially, there is much more going on in the surrounds with the source tracks than I normally would mix. In that regard, Steven’s score is hung more toward the screen, and the surrounds are more conventional. To envelope the audience, I made the music that Baby is listening to pretty wide in both the surrounds and the height speakers. Sometimes these tracks are also played pretty high in the mix, so I had to do a fair amount of EQ — sometimes radically — so that ear fatigue for the audience was not an issue.”

Slater spilt effects and design over “Twelve or so food groups, such as Baby Car Engine, Baby Tire Skids, Guns, Gun Impacts, etc., with the backgrounds taking up another six. We then had further food groups specifically for effects, including Car Engines and Skids, that were woven musically into the movie. These were the effects that had been pitched or timed to work with the music at that particular point in time. This way, if there was a music edit from the cutting room, we knew which tracks had to be looked at again from a musical perspective.”

Slater kept everything in the box throughout the entire editorial and re-recording process. “It lets me retain all my sound ideas right through print mastering,” he explains. “For Baby Driver, we pre-mixed to a 9.1-channel bed with Atmos objects, and brought that sub-mix to Goldcrest, where we could open everything seamlessly on the Avid S6 console and refine all my dialogue, music and effects sub-mixes for the final Atmos immersive mix.”

Once Slater moved onto the Atmos stage, “I then set about using the objects within the mix, of which there is a fair amount going on,” he acknowledges. “There is an amazing single-take sequence early on in the movie that tracks Baby as he walks down the street. The entire sequence is choreographed to his music choice. All the world sounds are constantly panning around him as he turns and the camera moves around him. Car alarms, sirens, music from cars going past, etc., are all syncopated with his music track and panned around in the Atmos accordingly. It’s quite a sequence!”

All of the sound editors had access to all of the DAW plug-ins needed to run their Pro Tools sessions, Slater confirms. “This was a major advantage, because Edgar would come into my cutting room to hear a sequence way before we hit the stage, yet still be doing mix notes,” he explains. “There are various fader moves and sound ideas that were made in my cutting room months before we mixed the movie that made it through to the final dub.

“Once we hit the mix,” he continues, “I took care of all the effects and design, plus source and score music as they were woven together. For the temp mixes, I also had any dialogue and Foley that worked with the music, with Tim Cavagin taking care of those elements through the mix.”

Slater’s biggest challenge, he recalls, was keeping the constant premise of the sound design and music working together pretty much all the time, but without it becoming a distraction or even tiresome for the audience. “There was a constant self-checking process that I did in that regard,” he says. “We had to be as subtle in our approach as much as we were obvious. Having said that, there is a lot of sound design. This movie has so many audio Easter Eggs of elements working within the musical pieces; I don’t think anybody will spot them all!”

Having worked with Wright on all of his movies — Baby Driver being the sixth — Slater is known for his care and attention to sonic details during post-production. “The thing I love most about working with Edgar is his love for the process with regards to the sound design and mix,” he concedes. “Edgar really thinks about sound very early on in the process. It’s no coincidence that the final soundtrack for each of his films is not only bold but very unique. There’s a real vision from him, yet Edgar still leaves me a large amount of freedom. It’s never a case of, ‘It must sound like this!’ I would describe it as more of a template that he designs and hands over to me. Then he’s happy for me to expand on that template.”

Slater is currently working on director Jake Kasdan’s Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle at Sony Pictures Post Facilities.