by Staphanie Argy

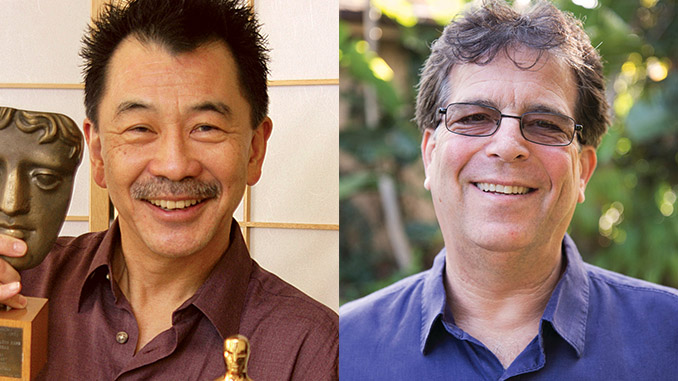

In the second part of their conversation, film editor Richard Chew (I Am Sam, Shanghai Noon, That Thing You Do!, Star Wars (co-editor), One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (supervising editor), The Conversation (co-editor), Risky Business) and Curt Sobel, music editor (An Officer and A Gentleman, La Bamba, The Insider and the upcoming life story of Ray Charles, Unchain My Heart) and composer (Alien Nation, Cast a Deadly Spell, The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones: Transylvania) talk about how digital technology has affected their jobs, the recent trend toward shortened schedules, the difference between tracking and working with a composer, and more.

Richard Chew: As our working methods change, is music editing decentralizing so that you are working more at home than at the studios?

Curt Sobel: My studio has been at our home for many years. Digital editing hasn’t changed that for me. When we were on mag, most directors and I worked together in my home studio. Getting directors out of their production environment or editorial rooms can be an advantage. They are then able to give full attention to what I’m presenting. For me, it’s great to be able to have my studio directly at hand. When creating a temp, I become totally consumed with the project and want to be able to immediately try possible scores against the film. Normally, my working day starts at 5 a.m. This schedule makes it possible to lay out new ideas as well as have answers for the director before the start of the studio workday. It helps move the temping process along. At some point, however, I do move to the post-production location. This may be to be closer to the dub or because we’re running into a time constraint when the need for immediate decisions becomes paramount.

Chew: I think it works well for a music editor to do that. Working at home appeals to me in a personal sense, but I don’t think that it would be creatively fruitful for me as a picture editor. I like the interaction with other people. There’s a partnership between director and picture editor, especially when we’re trying to find the film and give it style and pacing, and I think you need to be in each other’s presence. Also, picture editors need to be with their staff of assistants, because we’re dealing with labs and other vendors.

Sobel: You have a large staff. But music editors seldom do. I’ve had an assistant on very few shows during my career. I’ve always felt that if I do the work myself, I sleep better at night.

Chew: Do you see the changing technology affecting the workload and job opportunities for assistant music editors?

Sobel: When we worked on mag, assistants would prepare cue sheets and keep track of outtakes and maybe do slating on a recording stage. Those tasks still exist to some extent. With the new technology, assistants are archiving, restoring, formatting hard drives and loading sound material. Those tasks have been added to their job description. For this reason, I would assume there are more job opportunities for them. But personally, I rarely use assistants.

Chew: You use Sonic Solutions, whereas a lot of other music editors use Pro Tools. Why is that?

Sobel: I was one of the later music editors to get into digital editing. I was very happy doing mag work for many years while others worked out the bugs of digital technology. When Taylor Hackford asked me to work on Dolores Claiborne, I made the switch. At that time, 1995, it was felt that Sonic produced a higher quality of sound. Some feel that Sonic still sounds better. Sonic, however, was viewed as more difficult to learn. Even though the cost at that time was more expensive, for me Sonic was more versatile. At one time, directors who were used to Pro Tools were amazed at what I was able to do with the Sonic system. I must confess, though, I’m considering adding a Pro Tools to my studio. I’m afraid the time has come. Pro Tools seems to have become the norm with area music editors and is found in most recording studios. It can trade files with the Avid system, and it has enormous track playback capability. Editorially, it may lack some of Sonic’s finer points, like having multiple EDLs (or sessions) open at one time, simple Mac copy-and-paste functions from one EDL to another, and the most important to me, being able to place comments or sync marks with descriptive sentences on any piece of audio track. This is a lifesaver in terms of sync issues and keeping track of choices.

Chew: When we were using mag for sound and music, we couldn’t do all these temp mixes in the editing room before screenings. Now that we can, I find there’s a lot more pressure to do them there and bypass the dubbing stage. Most times they include music tracks that have gone through your hands, but a lot of times they use tracks that picture editors have recut. Do you feel that limits what you do?

“What comes first, content or form?… I believe content comes first. The projects I choose are by and large heavy with content; consequently, when I work with that material, I work on story structure and character development, and let that content dictate the form or editing style I bring to it.” – Richard Chew

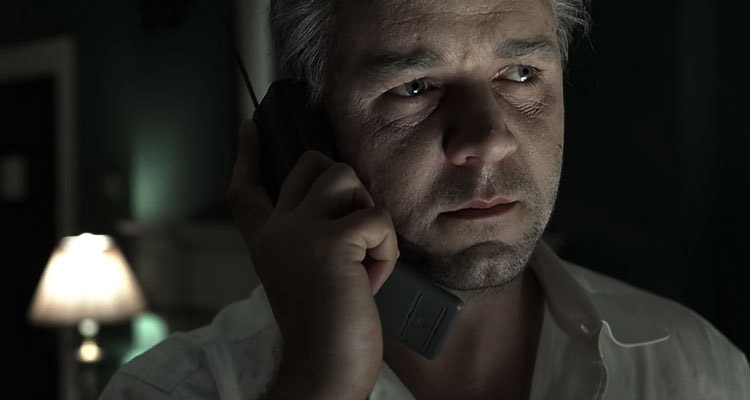

Sobel: It doesn’t hamper me one bit. Any work an editor or director does in the Avid is helpful. You may be bringing me on to help you find music and fine-tune what you’ve already done. I have no problem with that. I’ve been in many situations where I’m giving music to the film editor and they’re inputting it into the Avid — or vice-versa. On The Insider, I was getting new scenes on an hourly basis. I had to re-conform, re-cut the music, and then give it back to the editors so that they could re-input it into the Avid. Once in the Avid, the editors would re-cut the scene and output it, so I could re-cut the music (and around and around we go).

Chew: While I’m tuned into the musical choices for a scene or for the film, I don’t always know how to make a musically acceptable cut. If I want to take out the middle of a cue or put a new ending on it because it’s too long, I rely on you, as music editor, to make it sound like it was written and recorded that way. Which brings me to the difference between music editors who work for a composer, and those who put together a temp. Can you talk about that?

Sobel: Over the years, we’ve seen a division appear in the role of the music editor. Twenty-two years ago, I would begin a project by compiling notes for a composer and creating a temp score for screenings. That temping process would end, and we would record the score and prepare for the final dub. Now, on many schedules, you are temping on one stage and doing the final on the next, so it may be necessary to have two music editors working on the film at the same time. Composers need a music editor to work as a liaison between them and the director, producer, editor and studio, representing their interests on the dubbing stage. But at the same time, temp dubs are being performed so that various versions of the film can be screened to fine-tune the editing and storytelling. Some music editors have told me they prefer not to do the temps. Personally, I like both parts of the process.

Chew: It’s peculiar, isn’t it, how the post-production schedule has collapsed into these simultaneous processes?

Sobel: I think the advent of digital editing has exacerbated that and certainly accelerated the process. Another thing that’s happening is if I’ve placed a lot of songs in the temp that will eventually stay in the final, I’m asked to stay on board and handle that material, while another music editor comes in for the underscore, working with the chosen composer. On numerous films, such as The Majestic, I Am Sam, Evolution and Proof of Life, there were multiple music editors on the stage because of an overlap between temping song placements and finaling. By the way, on mag, it would have been very difficult to keep track of all the spread-out multi-tracks, variations and alternates. But with the EDLs and sessions in Sonic and Pro Tools, keeping track of all options are much easier.

Chew: You’re known for your work as a music-tracking editor. How did that happen?

Sobel: I’ve been tracking ever since starting as a music editor back in 1979. I’ve been accumulating soundtracks since I was in high school, so my collection is quite extensive. The processes and responsibilities of the two types of music editing are very different. Temp tracking is a very challenging and creative process to me. For example, on Airplane, no one was initially quite sure how to score the film — the humor was so new and different. It was my idea to use old-fashioned orchestral film music, instead of comedic “stings.” I thought old-fashioned film scoring might be amusing against this very broad verbal and visual comedy, so I brought in numerous examples of melodramatic orchestral music, in particular Miklos Rozsa scores for The VIPs, Fedora and other things of that ilk. The directors (there were several) loved the approach, and when Elmer Bernstein wrote his final score, he captured that same old-fashioned orchestral feeling.

Chew: How general or specific might your guidelines be?

Sobel: Sometimes ideas for temp music are laid out by the film editor or director, who may have placed some score or songs in their Avid as a guide. Some prefer to edit against music, even if it’s not exactly right, because it helps them find initial moods and emotions that might work as they tweak the picture. Although I’m usually given a somewhat clean slate, many ideas are suggested to me during the initial spotting session. I consider all of these suggestions, but in the end, I select and propose the music that I feel will work best to make the screenings successful.

Chew: When might you suggest not using music?

Sobel: Many times, if the scene is working and doesn’t need any extra support or emphasis, placing music over the scene can be tedious and redundant and may even de-emphasize the role that music can play in telling the story. Too many starts and stops can become distracting to the audience and take them out of the movie. Also, sound effects are so important these days that music has to leave room for them if that’s a more effective way to tell the story for that moment.

“You must be able to lead yourself into the scene and really feel it. There is no substitute for listening, and listening takes time.” – Curt Sobel

Chew: Many recent films are cut very fast and seem almost like continuous montages, very dependent on music. They’re like music videos, and why not? Many new directors and editors come out of videos and commercials. All of which brings up a very old issue in art — what comes first, content or form? For myself, pictures like Moulin Rouge have form determining content. But I believe content comes first. The projects I choose are by and large heavy with content; consequently, when I work with that material, I work on story structure and character development, and let that content dictate the form or editing style I bring to it. For instance, compare Risky Business with Shanghai Noon, or with I Am Sam. Stylistically, they’re pretty different. Why? Content should determine form. Looking at film tradition, an alternative approach to montage is mise en scene, where you let the story play out the way that it’s staged and just hold on what the actors do, rather than doing a lot of editing to keep the audience interested. I can’t think of a better example than a Jim Jarmusch picture, like Mystery Train, or the movies of the Japanese director, Yasujiro Ozu. Those films just allow scenes to play out in master shots. You look at Jarmusch or Ozu, and then you look at Moulin Rouge — such different ways of telling a story. And I wonder, since we’re fascinated with the Moulin Rouge style right now, whether the pendulum is going to swing back the other way. Maybe audiences want to feel and look and think more about what they see.

Sobel: That’s what I liked about In The Bedroom last year. The filmmakers just let the drama unfold and didn’t push us through it. So there are people out there trying to work — I don’t want to say in an old-fashioned way — but maybe in another way.

Chew: I don’t see it as old school at all. Art is like current events and history — the only thing that’s the same is that it changes. Again it’s form versus content. Maybe sometimes when you lack content, you rely on form. Many of our films today don’t have any substance, so they draw you in by giving you a lot of eye candy. But what are you absorbing from them? Are you getting any insight into the human condition? Or learning how to make a world that values life? But maybe it doesn’t matter, because people go see movies to enjoy themselves for a couple of hours. I suppose if they want to educate themselves, they’ll read a book, or these days, they’ll go on the Internet. But I was drawn into film by the neo-realist movies — that’s what inspired me, that kind of storytelling. I started in documentaries, so of course, what would interest me in fiction film is neo-realism, because it has that same kind of grittiness.

Sobel: Thinking back, what inspired me to get into film was listening to Jerry Goldsmith music as a teenager. I would go to a movie just because he had scored it.

Chew: Do you remember some of those early pictures that he did?

Sobel: Absolutely! Lilies of the Field, The Blue Max, A Patch of Blue. And I collected Goldsmith soundtracks since the ’60s.

Chew: What about schedules? Are you given enough time to do the work you’re asked to do?

Sobel: My sense is whatever time is given, it becomes the amount of time that it will take to complete the work. But I got a call to do a temp recently. They called on Tuesday and wanted completely new music for the entire film on the dubbing stage by Friday. I said, “You’re kidding, right?” I was very polite in turning down the work, but I explained that with the limited time proposed, I could never fulfill their expectations. Their schedule did not allow the minimum amount of time to create, evaluate and approve an effective temp. In this case, I found there was a breaking point with the schedule. Post-production supervisors who understand what it’s going to take to get something accomplished can be extremely helpful, because there are those out there thinking that what we do is instantaneous. “Great, you’ve got digital equipment — I need something by tomorrow, can you drop it off for me in the morning?” Sometimes it can be done, but I feel that we have to be very careful and not just say “yes” to everything.

Chew: Producers and executives feel that because we have random-access editing systems, we can do things faster. But that doesn’t mean that we can think faster or come up with solutions faster. You still have to ask, do you feel anything from it? Do the characters work? Is it funny? Having a better piece of software doesn’t solve those things.

Sobel: You’re right. It doesn’t address the evaluation process. Do I want to go with this take or that alternative orchestra performance or no music at all? You still have to sit with it, live with it and screen the movie from the beginning of the reel, not just from the middle of the scene. You must be able to lead yourself into the scene and really feel it. There is no substitute for listening, and listening takes time.

“Working at home appeals to me in a personal sense, but I don’t think that it would be creatively fruitful for me as a picture editor. I like the interaction with other people.” – Richard Chew

Chew: Sometimes there are hours of dailies for a short dialogue scene. It may take you a day to review the material, make your notes and start putting something together — and another day to make it work. That’s two days, just to put together one scene. I’ve asked some other editors how they do it and I’ve heard this answer: “Don’t tell anybody, but I just use the last circled take.” They don’t have the time to study all the footage, so they choose one take arbitrarily and use it. I believe that can really shortchange performances.

Sobel: If you have to work a shortened schedule, I think you’re obligated to explain to the director and studio what will be sacrificed, and then let them know the amount of time you’re going to need in order to professionally accomplish what you’ve been asked to do.

Chew: Many of the pictures I work on are smaller pictures that are lucky to get made. I Am Sam took about six years to get off the ground. Sometimes I’d rather sacrifice some extra bucks on my part to help the picture get made — but whatever the budget, I need time to feel the performances and the rhythms, to find the scene, the characters, the film. The more film there is, the more this is true. You can’t do the job if you don’t put in the time and let the film affect you. You’ll jump to conclusions too quickly and won’t be able to shape the material as well — just like you can’t create a great score unless you have time to find the music — the right music for the scene, the beat and the film as a whole.

Editor’s Note: To see the preceding comments of this conversations, read part 1