by Leslie Shatz

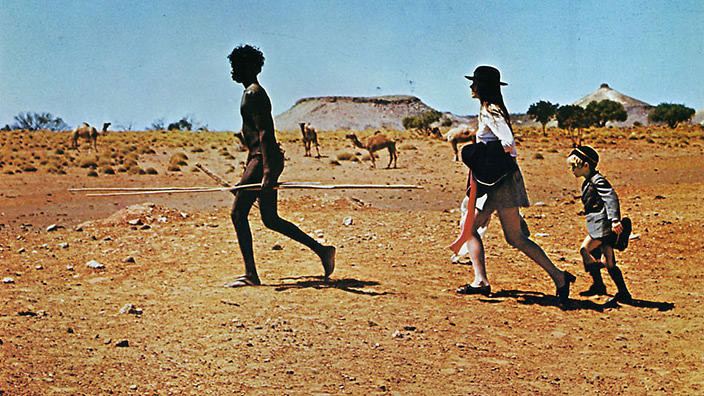

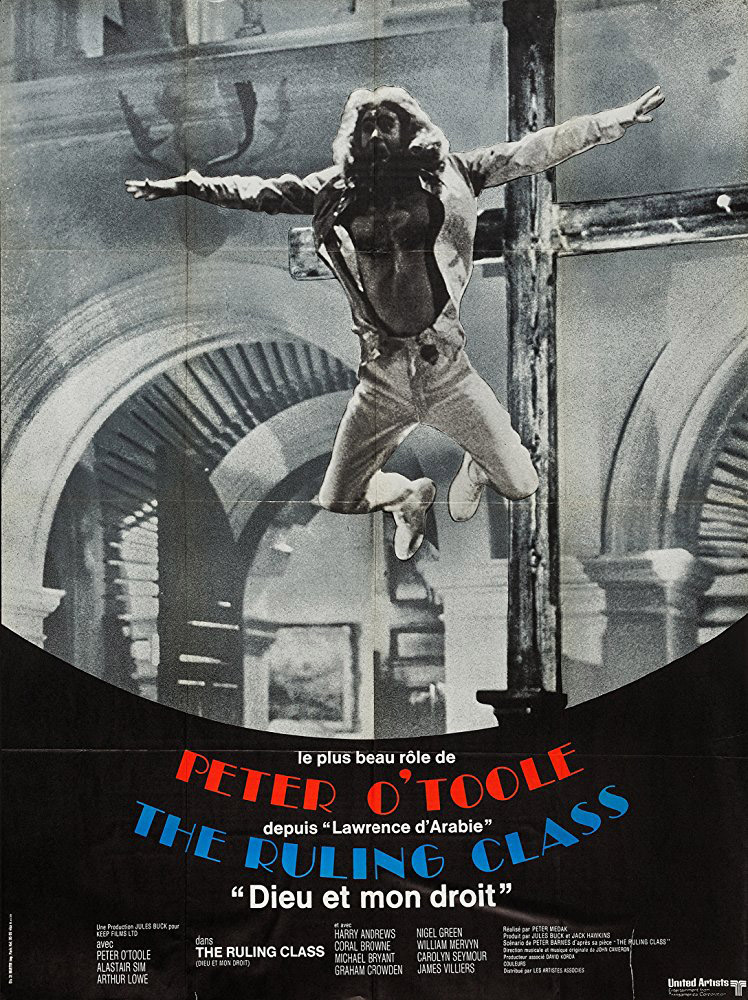

Gerry Humphreys’ name has long been synonymous with motion picture sound in Great Britain. During his illustrious career he has mixed over 200 films for such directors as Richard Attenborough, Richard Lester and John Schlesinger. His credits include Cul-De-Sac, Petulia, The Lion in Winter, Walkabout, Sunday, Bloody Sunday, The Ruling Class, A Bridge Too Far, Blade Runner, An American Werewolf in London, Ghandi, A Fish Called Wanda and The Sheltering Sky. He was born in Wales in 1931 and grew up in Esher, a suburb of London. He started his career in sound at the Walton Studio in 1947 as a tea-boy and runner, then worked his way up to boom operator for Lewis Milestone’s film Melba in 1953, the first time that a sound truck fitted with a 35mm magnetic recorder (converted from optical) was used in England. He received his first break as a re-recording mixer on Roman Polanski’s 1965 film, Repulsion. During his 55-year career, he has weathered many changes in sound technology, from mag to “rock and roll” recording to automated consoles to digital sound, without missing a beat. He recently received the Order of the British Empire for his work in promoting the film industry in Great Britain. His diverse background gives him a unique perspective on the making of movie soundtracks in Europe. I interviewed him in his office at Twickenham Film Studios where he is the sound director, and where he has worked since 1963.

Did you know when you were working on the Beatles’ movies that they were going to be special?

No. It was that period, an old cliché: If you can remember the ’60s, you weren’t there. But it was certainly exciting, because not only did we do the post production here, but also the actual film was shot here in these studios. Every morning, in that little close [dead end street] outside the front of the studios, there were at least 400 screaming girls. And they used to try to climb over the wall and get into the lavatories, so in case one of the Beatles came in, they could actually see them and talk to them.

When Richard Lester, the director, was shooting Help! on the stage here at Twickenham, I was dubbing Dick’s previous picture. He would come into the dubbing theater at night and I would play back what I’d done and he would make suggestions. One day after lunch, Dick popped his head in and said, “You know, we haven’t got a title song for this picture. Would it be all right if we used the grand piano on the dubbing stage? Would it be all right if the boys came in and played?” So, in came John and Paul and sat down at the piano. Tink, tink, tink, and they were literally writing it down on the back of a fag [cigarette] package. And they played around, and then the assistant director came in and said, “We’re ready for the shot now, boys,” and off they went, back to the set. That night, they went up to their studios in London, did some more tinkering, came back the next morning, brought Dick Lester into the dubbing theater and sat down and played Help. That’s the first time they played it — and this idiot here didn’t roll a tape.

You’ve worked on so many films — do you find it hard to adapt to the individual style of each director you’ve worked with?

I worked with many directors with different styles, through the ’60s and ’70s. There was Sidney Lumet, Dick Lester, Roman Polanski, Joe Losey, John Schlesinger, Franco Zefferelli, Tony Richardson …

“There was a group of people that walked up towards us after lunch, flower power shirts on, long hair. “Who are these guys?” I asked. He said, “Oh, they give me such a hard time. They want to do stereo recording and things like that. They’re driving me crazy. They shot some concert someplace called Woodstock or something.” – Gerry Humphrey

What was your approach with Sidney Lumet?

Sidney would probably admit that he doesn’t like dubbing much, because he’s such an active person.

So when he came in, you knew it had to be as quick as possible?

Absolutely. We did a reel one night and he said, “Yeah, yeah, that’s a print, that’s a print.” I said, “That was sort of, really only … a rehearsal, Sidney.” “No, no it’s fine.” And he went home.

So I went back and re-mixed it. When he came in the next evening, I said, “I think I ought to play back that reel to you. I had another go at it after you left.” And he said, “Okay, let me hear it. … Yeah, yeah, that’s fine. Okay, bye.”

How about Richard Attenborough?

He’s very, very keen to hear his dialogue. I like working with him. He gives you quite a free hand. And, very, very appreciative. I mean, he’s an actor. So, he likes to hear the words.

You did a Nick Roeg picture with Mick Jagger — Performance. What was your approach with him?

Basically, to use the original at all costs. It’s got to be pretty bloody before he will loop anything. That certainly applied to his picture Eureka.

Performance was one of the essential films of my youth. It was so … risqué. Were you uncomfortable with what was going on?

No, not really. It was that period of time. People had come out of the ’50s, which was a boring decade, certainly over here. The war had just ended, and there was still rationing going on; it was just a dreadful period. And then, you came into the ’60s, and you got “swinging London,” and Mick Jagger comes along and drugs, and then bingo, everything happened.

Did you see a lot of drug use on your stage?

Yes, quite a lot. Quite a lot.

How did you handle that?

Totally detached. Definitely an anti-drug man, me.

It must have been hard, though, with…

You’re looking at a person who hasn’t even had a joint, never mind about inhaling or not inhaling. Drugs were done here by a lot of people — I don’t think I should name names. I don’t know what happens inside their brains, but they hear something that’s certainly not coming out of those speakers. There was one film they were mixing at night and I used to arrive in the morning and look at the console and see the EQ and I thought, “There’s not a track in the world that needs that much EQ.” They then came to me and said, “Gerry, are you sure your machinery is level and everything, frequency-wise?” They would play it back the next night and say, “Oh, Jesus, we must have done something strange last night. Wipe that — and off we go and try it again.” They were supposed to be here for five evenings. They stayed for seven straight weeks.

How would you compare mixing English and American mixing?

Well, I remember the first time I went to L.A. — I think it was 1970. I thought, “Oh Jesus, I’m going to Mecca.” I first went to Warner Brothers, and Al Green, the sound director at the time, was showing me around. We had been using “rock and roll” over here for at least a couple of years. [“Rock-and-roll” dubbing or “pick-up” recording was the then-revolutionary ability to stop a mix in progress, go backwards, and punch in and start recording again in the middle of a reel.] Mr. Green showed me a huge number of selsyn generators [used to interlock playback machines electrically] all locked to different theaters. But he couldn’t get the money out of his board of governors to get rock-and-roll fitted.

At that time you could go to most of the studios and fire a shotgun and hit nobody. While Mr. Green was giving me the tour, the whole Warner Brothers lot was completely empty. But there was a group of people that walked up towards us after lunch, flower power shirts on, long hair. “Who are these guys?” I asked. He said, “Oh, they give me such a hard time. They want to do stereo recording and things like that. They’re driving me crazy. They shot some concert someplace called Woodstock or something.”

So, you think that in those days, because you were smaller, you were able to adapt to technological changes more easily?

Yes. We’re a small little unit here, compared with American studios, and when new stuff comes along, I’ve been very fortunate to be able to get the money from management to purchase it.

But, how about now?

Oh yes. It’s changed a lot. For a number of years now, the center has moved back to Hollywood.

Do you think it’s because of cost? Or, do you think it’s because English filmmakers don’t really want that kind of sound for their movies?

A lot of it I’ve put down to the sound editing department here. They didn’t go along with the change in technology that took place when sound designers first came in via Los Angeles. Over here, all they were doing was cutting each other’s throats, never mind the quality. “I’ll do it for five pounds a week, I’ll do it for four — I’ll do it for ten cents.” The same old tracks were coming out. They were using loops and going to libraries and things like that. There isn’t a lot of imagination on that side over here and I think they lost a great opportunity. On the mixing side, when digital equipment started to appear, I know that the studios in Europe were ahead of L.A., certainly for 18 months or more. When I used to go over to LA, the digital stuff we were using here hadn’t taken off. But once L.A. said, “We think this digital stuff is here to stay,” they just threw a zillion dollars at it and vroom! — almost overnight everything changed.

How would you compare your working methods now with the techniques used when you started?

Well, multi-track. When you think of some of the consoles we used for the Beatles pictures or Alfie or …

How many tracks did you have?

We had 12 pots…

That was it? Dialogue, music, effects?

Dialogue, music, effects — 12.

Did you pre-mix?

Did some, but not a lot. The tracks were down to a minimum.

And, how long did it take?

A Hard Day’s Night, we mixed the whole lot in three weeks. That’s foreign version as well.

You didn’t have rock-and-roll capabilities on that film?

The first break I got as a lead mixer was on a Polanski picture, Repulsion. Roman lived in France, and there was a person in Paris called Nenni, who was the father of rock-and-roll dubbing — but he had done it almost as a mechanical thing with bicycle chains and things like that. There was a central spindle going through with cogs off to every machine. But it went back and forth and you could punch in. When I was doing Repulsion for Roman, he was talking about it. I had heard about this man and his system — you can go backwards and update — fantastic! I got in touch with RCA. Yes, they did do it, but no one was buying it. So I went to the management here, and they said “Oh no, no, no.” I got Roman to speak with them. “I’d like to do my next my picture, Cul De Sac, with Gerry, but I can’t because you don’t have rock and roll.” So we got it. I think it was incredibly expensive, about 9,000 pounds or something. It was like magic — you could make a mistake and roll back and erase it.

Do you find that even with all these modern conveniences, mixing is more stressful than it was in the past?

No. In those days, before rock and roll, you used to get sweaty palms. You’d say, “Okay, we’ll go for a take.” You knew that if you blew your bit, you were also going to blow it for the dialogue mixer or the music mixer. There was a tension. When rock and roll came in, it took away 90 percent of that — if you made a mistake, you could just roll back 20 feet and update it. Today there are other problems that have come along, like the amount of tracks being delivered to the stage. And now you’re finessing things right down to the frame. “Lord, there’s an empty frame there, let’s fill it with something.” There was a lovely period of about two years, when rock and roll first came in, when directors did not fully understand what we could do. You’d roll back, punch in and update — by the time they had really caught on to what you could do, you had dubbed the picture. But then they realized the potential of it and they started asking you to do things they’d never asked for before. This was before you could go high speed, and they’d say, “You know I’d like to redo that music entry at 800 feet.” New problem — we can do a little thing in the middle of the reel, but it takes a long time to get there!

What do you think of this trend towards louder and louder movies?

I think it’s very bad. I think it loses the finesse of dubbing. Also, I think, especially in your country, where they are very litigious, someone is going to say: “I walked into this theater and I had 100 percent hearing and I’ve walked out and now I can’t hear anything. I’m going to sue you for it!”

The films that are recognized for sound are usually loud films. It seems like we’re being encouraged to make pictures louder.

I know in your country there are some mixers working with earplugs. I mean, what is that about? But I’m sure the directors are saying, “No. We want more. More, more, more, more.”

“You’re looking at a person who hasn’t even had a joint, never mind about inhaling or not inhaling. Drugs were done here by a lot of people — I don’t think I should name names. I don’t know what happens inside their brains, but they hear something that’s certainly not coming out of those speakers.” – Gerry Humphrey

We had an article recently in our magazine looking at the trend in England against unionism, and in particular, what’s happened to your film union.

Which is now non-existent.

What happened? I know the union in England, ACTT [now BECTU], was very strong at one point.

It was very strong. It insisted that if you fly anywhere, it was a first-class seat. And it determined the amount of crew that you had to have. There were excesses, certainly. But the government with Margaret Thatcher broke the unions. And her great pet hates were the television industry and the film industry. She had heard of people in television that were making 150,000 pounds a year to be an editor on a show for two nights a week, and all this was blown up in the press. She broke the unions, without a doubt. Now, the unions here are non-existent. Absolutely gone. The working hours and conditions are now controlled by the European commission, rather than by a trade union. That you mustn’t work in excess of so many hours, with so many days off and things like that — this is European law, not a union rule.

Do they understand how the film business works? If you’re working for a film and they commit some kind of infraction and then the film is finished, who are you going to take to court?

Yes, that’s a problem. And the film industry got a special dispensation so that the rules are spread out over 12 months. A producer might be breaking the rules in this three months, but then they don’t break for them for the next nine months and they’re okay. But, of course, afterthat three months, you’re on to another picture.

Do you think that the sound editors are overly competitive due to a lack of standardized working conditions?

Yes. When the unions went out, and the sound editors lost the protection of the unions, they were all cutting each other’s throats.

Was the quality of their work suffering, as well?

The overall quality, without a doubt, dropped. If you asked why something wasn’t done, they would say, “We didn’t have time.” It’s a chicken-and-egg situation. “If I didn’t say we could do this picture and lay it up [build the effects] in six weeks, I wouldn’t get the job.” Then someone else will say: “If he’s going to lay it up in six, I’ll lay it up five.” And, it went on from there. Without wishing to sound patronizing in any shape or form, much better stuff is coming out of America. I’ve been conscious of it for a number of years. When you go to academy screenings, and say about an American film, “That was a bloody good soundtrack there,” people will answer, “Yeah, but did you see how many people were on the credits — 27 editors, 46 assistants!” I’m not interested in how many people there were. The quality of that track is what interests me.

I do hope that your unions stay strong. People don’t realize that if you haven’t got a person that is collectively looking after you, then you get this cutthroat business and wages will suffer. But also, without a doubt, the quality suffers, too. Producers are only human. And, I’m sure, if we were producers, we’d probably try to get it as cheaply as possible. I guess that’s what their job is, in a way. But the collapse of the union over here had a big detrimental effect on quality.

It seems to me that, since the consoles have gone digital, mixing studios have stopped making money. Everywhere I go, people are having trouble making a living doing this.

You can get a 48-track console for $100 — that’s an exaggeration, but it’s so cheap in comparison to the past — and now someone in a back room can do a little mix in their own home. Yes, it’s much more difficult now to make a living. Before, when some new piece of gear came on the market you’d say, “Fine, we’ll have one of those.” Now you’ve got to be really sure that the equipment is going to be around for a couple of years. You used to be able to amortize equipment over 10 years and it still worked after 15. No way do you amortize today’s equipment like that. It’s old hat in two years’ time. People like to use the latest technology. They’ve got to have this great big console, but they don’t want to pay the price. The rates that I was charging ten years ago are not much different today. But the equipment is. You’ve got to get more, more, more equipment in order to keep up to date. If you don’t, you’re dead.

Where is the business going, do you think?

All these little studios are doing mixes that take away what used be our bread and butter. Not the big extravaganza movies — they’ll always go into the big dubbing rooms. But there are lots of bread and butter movies that are now being mixed in a room not much bigger than your bathroom.

Are you referring to ProControl? [Digidesign’s hardware mixing interface for Pro Tools.]

Yes.

That’s the big rage now in the U.S. and there’s a big debate about it. Do you think it’s possible to do a good mix on one of those in a small room?

“When the unions went out, and the sound editors lost the protection of the unions, they were all cutting each other’s throats.” – Gerry Humphrey

I’m a great believer in the idea that you’ve got to have a bigger room. You’ve got to have the air around you. I’ve never felt comfortable trying to mix in a small room. I’m certainly not qualified to answer on the ProControl side of things. I have reservations about it now. But I’ve never attempted to use it, so I haven’t got any practical experience of doing it. I hope it never comes to that.

So, what’s your next picture?

For me? I probably won’t mix another one. Well, if Dick Attenborough does another picture I’ll do it, because he filmed eleven pictures and I’ve mixed all of them. I mixed one last year for Louis Gilbert. I don’t know how many of Louis’ pictures I’ve mixed, but quite a lot. On his last show, he booked the time and I put Tim Cavagin [Twickenham’s lead mixer] down to mix it. One day, I got a call in my office asking if I could go and see Louis, who was shooting on the stage. He said, “Oh, I hear you’re too proud now to mix my pictures?” “No,” I said. “I just thought you wanted someone young and vigorous.” “No, no, no,” he says. “We’ve grown old together.”