By Peter Tonguette

Last December, when audiences tuned into NBC’s live broadcast of Hairspray Live!, they encountered a familiar cast of characters.

The show — derived from a 1988 film written and directed by John Waters, as well as a stage show and subsequent 2007 film adaptation thereof — has its share of memorable personages. Consider Tracy Turnblad (played by Maddie Baillio), the teenager whose not-quite-beanpole proportions are no impediment to her becoming a hit on television in Baltimore in the early 1960s. Then there is Corny Collins (Derek Hough), the too-slick host of the dance show on which Tracy appears; Motormouth Maybelle (Jennifer Hudson), the African-American record-store owner who teams with Tracy to lobby for racial integration. And, of course, many viewers were sure to have a soft spot for Tracy’s parents, Edna (Harvey Fierstein) and Wilbur (Martin Short).

Less obvious to viewers was the presence of the artists and technicians who brought the show to screens during its three-hour airtime. Supporting co-directors Kenny Leon and Alex Rudzinski was a crew of about 700, including 13 camera operators scattered throughout a Universal Studios backlot dressed to resemble Baltimore Street. Ideally, their work would go unnoticed—after all, audiences should be wrapped up in the show, not what it took to bring it to air.

If all went according to plan, however, Charles Ciup’s job may have been most invisible of all.

As the technical director of Hairspray Live!, Ciup was at the helm of a switcher to alternate between the angles of the show’s 19 cameras (two were in locked-down positions not requiring operators and others were used by operators sparingly) at the prompting of Rudzinski and associate director Carrie Havel. So, when Tracy sang a song or Edna cracked a joke, Ciup was in charge of cutting to a close-up or a wide shot at just the right moment. His efforts just netted him a Creative Arts Emmy for Outstanding Technical Direction, Camerawork, Video Control for a Limited Series, Movie or Special at an awards ceremony in early September.

“It’s live editing,” Ciup says. “Even though directors are calling for the shots, and they’re calling for the tempo of the shots, you have that fine line: Are you ahead of the beat? Are you behind the beat? Is this where you take your shot? I can tell a story that way, and that’s what makes the job interesting to me.”

A native of Israel who spent his early years in Paris, Ciup was raised in Montreal, Canada. Initially intending to become a disc jockey, Ciup entered what was then known as Ryerson Polytechnic Institute in Toronto (now Ryerson University). After taking a class in television production, however, he decided that he preferred to work with both pictures and sound.

“As soon as I started taking TV production, I said, ‘OK, this is where I really belong,’” Ciup remembers. “This is where I get to tell a story. I was playing with flashing buttons and making things fly around the screen. That was heaven to me.”

In the year after his graduation in 1973, Ciup accepted a “summer relief” job at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). “In the summer, as their crews went on vacation, they needed people to come in and fill those jobs,” Ciup says. His responsibilities varied but he gravitated toward operating the switcher during live broadcasts.

“I thought that was a blast,” Ciup recounts. “You have to have a sense of rhythm and anticipation about what’s coming up next, where the cuts should happen and, if the director is calling for a camera and you know it’s the wrong camera, then you take a chance and take the right camera. Most of the time it works out.”

Ciup’s summer stint at the CBC led to an offer of full-time employment, but in 1976, he left the network for a station in Vancouver, where he worked as a technical director and eventually news director and producer. A decade later, he moved to Los Angeles, where he was hired to work in the news department of a burgeoning satellite network of UHF stations. When the network didn’t take off, he began freelancing as a news writer before returning to his roots as a technical director.

“It had been eight or ten years since I’d touched a switcher, and the technology has increased by leaps and bounds, but the basis of the job remained the same,” Ciup recalls. “The digital equipment that was for special effects was all new to me, but I learned it as I went along.”

In the 1980s and ’90s, Ciup hopscotched from children’s shows (Fun House) to game shows (Shop ’til You Drop) to courtroom programs (Judge Judy) before finding one of his most challenging assignments in Dancing with the Stars. In 2006, Ciup was asked to cover for technical director John Pritchett on ABC’s hit dance-competition program (helmed by future Hairspray Live! co-director Alex Rudzinski).

“They called me and said, ‘John is doing the show, but he has a few conflict days because he’s doing American Idol. Can you fill in for him?’” says Ciup, who agreed to take the assignment. When Pritchett decided not to return, Ciup became the show’s regular technical director.

Years later, with Rudzinski directing Hairspray Live!, Ciup joined the project as technical director, although little in his career provided preparation for the ambitious live broadcast — not even the song-and-dance elements of Dancing with the Stars.

“It was new in that I’d never done live musical theatre for television,” Ciup observes. “It was not new in the sense that half the script was sitcom and half the script was music, and I’d done both. Putting the two together was an intense experience — the most intense experience I’ve ever had.”

Before he could dive into the tale of Tracy Turnblad, however, Ciup had to make sense of the script, which was about seven times the length of a typical music script for Dancing with the Stars. “I get these two gigantic binders dropped off at my door, and they’re a total of about 700 pages,” he says. “I thought, ‘There’s no way that I can turn that many pages in a three-hour time span and not make a mistake.”

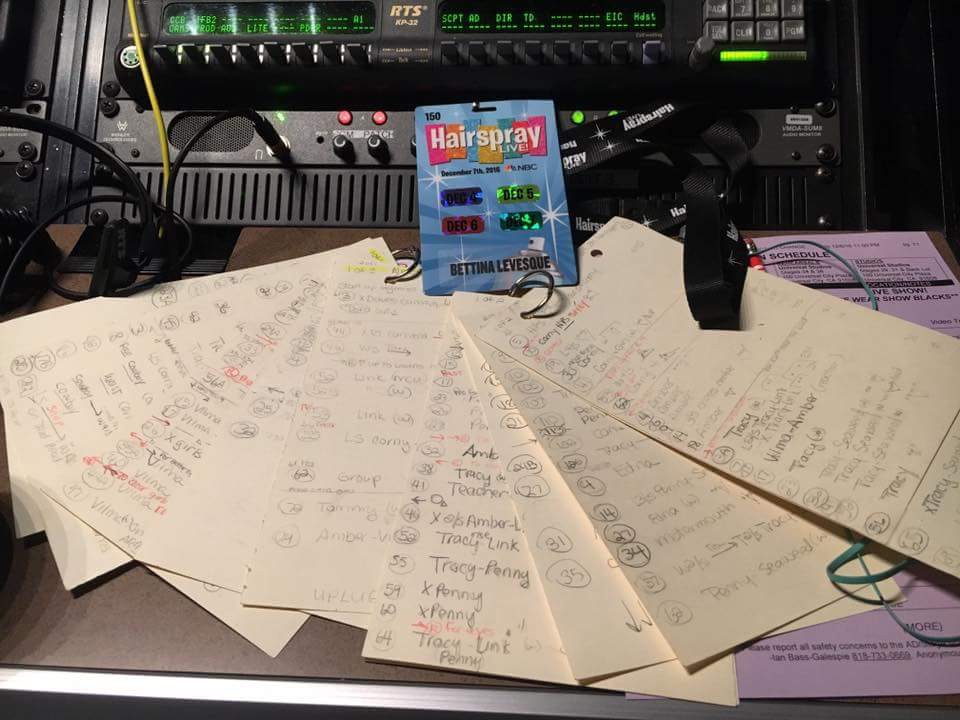

Looking for guidance, Ciup contacted fellow technical director Eric Becker, who had worked with Rudzinski on Fox’s Grease Live! “He had broken his script up into three or four different binders, and he had rewritten his shot lists in his own way so that he could follow it,” says Ciup, who made his first stab at reducing the page count by having the script reprinted on double-sided pages. “Now I’m down to 350 pages.”

He also eliminated the lyrics to songs during musical numbers. “I’m strictly looking at the bars and the beats of the cuts, so I didn’t need all that in the script,” he says. “I just needed to rewrite the bars and beats and what the shots are.” Ciup divided the script into three columns. “I started marking: ‘Shot one: three bars, camera two. Shot two: two bars, camera five. Shot three: six bars, camera one,’” he recounts. “I reduced probably close to ten pages of music script onto one blank three-column page, and that ten-to-one just made it so much more manageable.”

Rehearsals were held during the week-and-a-half before the show’s broadcast on Wednesday, December 7. “We tried to do all of the scenes that happened in the same location together so that we spent as little time as possible moving equipment and as much time as possible rehearsing,” Ciup comments. “Rehearsals were just as intense as the live show because we rehearsed as if we were on the air. We wanted to know what the tension was going to be like.”

On the Monday of the week of the show, a dress rehearsal took place. “We plowed all the way through and if something didn’t work, we just keep pushing,” Ciup says. The next day, a full run-through — with final costumes and lighting, plus a friends-and-family audience in attendance — was recorded. “That recording was a backup to the live show in case a wind came up and blew the sets down or it started raining,” Ciup explains. “We had a complete show that was ready to go to air that we shot the day before.”

At last, on the day of the broadcast — set to air at 4:30 pm on the West Coast, 7:30 Eastern — Ciup sat down at the switcher, which he reprogrammed to meet the demands of a 19-camera broadcast. “I played piano when I was younger, and I have a pretty good hand span, so I can do 10 or 11 cameras under one hand,” he says. “With 19 cameras, I have to take my eyes off the script and look down at my hand, and that’s not a good thing to do in the middle of a fast-paced show. In a trick I learned from technical director Allan Wells, I created macros that allowed me to place additional cameras above the first five cameras so that everything was within seven buttons.”

As the show began, Ciup experienced the usual butterflies, but quickly settled in. “You fade out from black and you roll the opening credits and the crane starts to come down, and you’re doing the show,” he says. “You don’t have time to think of anything else. You’re in the script, and away you go.” The first of 11 commercial breaks came 20 minutes in. “That opening act was about 20-some minutes long; that’s as long as a half-hour sitcom!”

Associate director Havel called “the bars and the beats” during musical numbers. “She’ll go, ‘Shot one, three bars — two, three-four; two, two, three, four; three, two, three, four,’” Ciup explains. “I’m counting along with her, because if she loses count, I’m in trouble. And she never lost count in calling nearly 1,700 different camera cuts.”

As the show unfolded, however, Ciup had to think two or three moments ahead. For example, one scene called for the use of a “noise effect” on a black-and-white television set being switched on in the Turnblad household. “They’re watching in the living room so that it looks like they just switched the TV on,” Ciup explains. “That’s a special effect I have to pre-set, but I only have a very small window to do that.” During commercial breaks, controlled mayhem ensued — “Sets were being moved around; cameras were flying from one place to another; actors were getting into golf carts…,” he recalls — but the technical director used the pause in action to regroup: “I was looking ahead at the next act in the script. And, having rehearsed it so many times, I pretty much knew where we were going.”

In the end, Hairspray Live! was transmitted to airwaves without snafus or missteps, so Ciup’s job remained invisible. Interestingly, prior to being hired to work on the show, he was unfamiliar with Hairspray in its earlier iterations. “I hadn’t seen any other version of Hairspray,” he says. “I didn’t know very much of the music — just the last song, ‘You Can’t Stop the Beat.’” But he left the three-hour broadcast, and the months of preparation that led up to it, with admiration for the project and its performers, whose talents he helped transmit seamlessly to audiences from coast to coast.

“How do you dance and still have enough breath to sing?” Ciup says with a sense of awe. “I can’t imagine.”