by Peter Tonguette

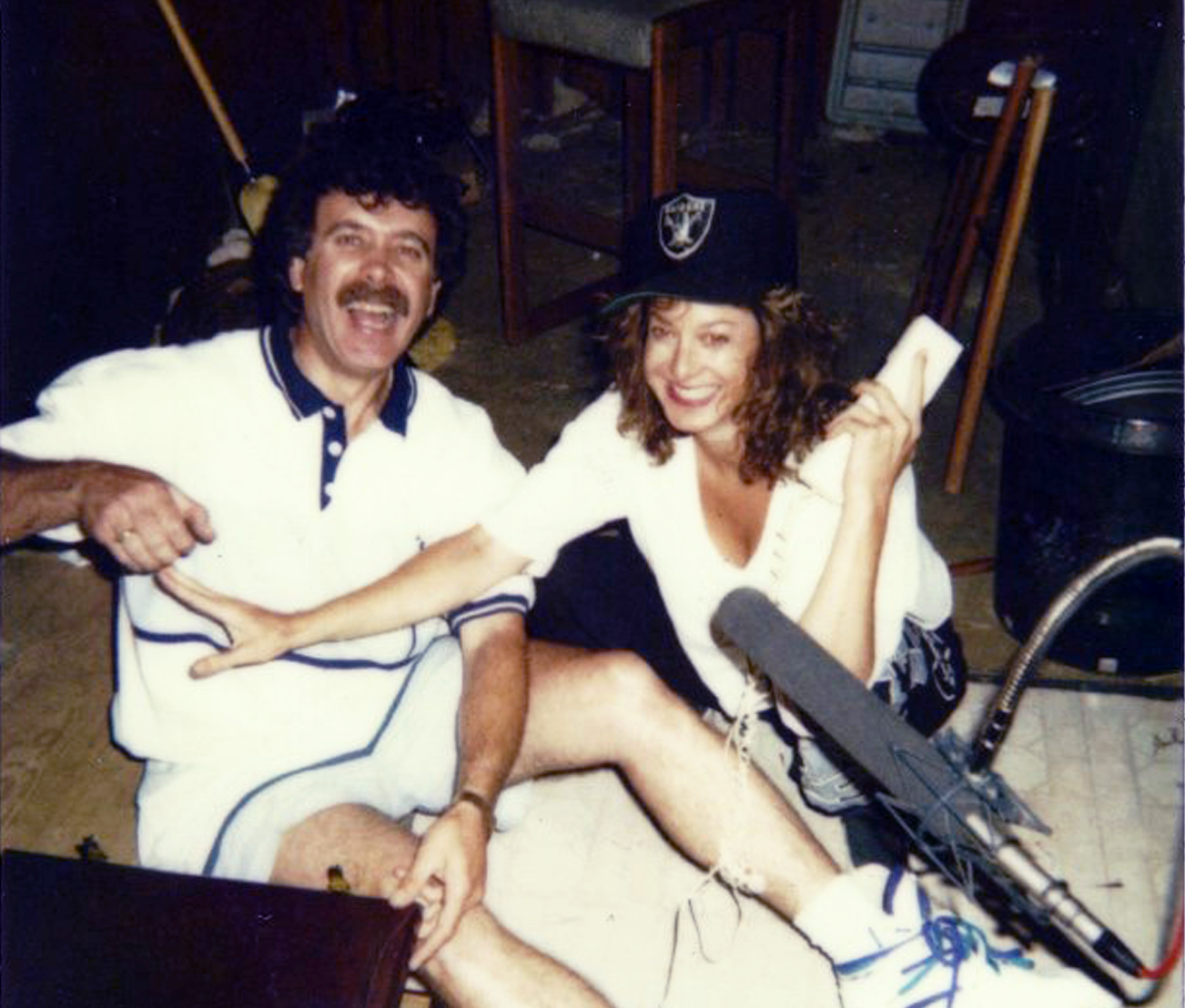

Foley artist Catherine Harper, MPSE, remembers the first time she encountered filmmaker David Lynch. In 1996, she was employed at Digital Sound and Picture in Los Angeles, where she and her colleagues, Ossama Khuluki and Ellen Heuer, were about to start creating Foley sounds for Lynch’s upcoming film, Lost Highway.

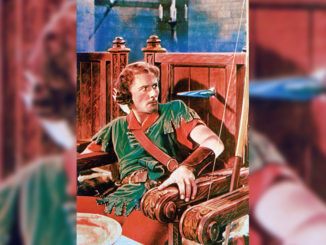

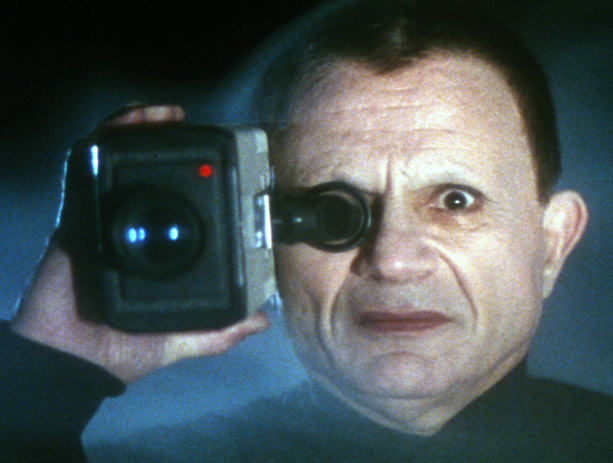

The film, released the following year by October Films, concerns a series of enigmatic events that engulf jazz musician Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) and his wife Renee (Patricia Arquette)., who become perplexed when they find themselves recipients of videocassettes depicting them inside their own residence. But the trouble really begins when Fred faces a charge of murder. Also featured in the logic-defying screenplay by Lynch and co-writer Barry Gifford are mechanic Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty) and ruthless ruffian Mr. Eddy (Robert Loggia) — not to mention the Mystery Man (Robert Blake). Critics were tepid and box-office was so-so but, like most Lynch films, it has acquired its share of admirers.

One day as Harper was preparing to start work on the film, she returned from lunch to find a smartly dressed man sitting on a metal folding chair in an alley leading to Digital Sound and Picture. “He was in a white pressed shirt and khakis and was smoking a cigarette,” Harper says. “The ashes were falling all over his shirt. He said hello to me, and I thought, ‘Who is this guy?’”

After a few moments, Harper — whose job calls for her to generate sounds in post-production to match actions on screen — realized that the man in the chair was none other than Lynch. “He stood up and opened the door for me,” Harper recalls. “He was really personable and so nice and approachable. After that, when I would see him at various times, he would always say hello and address me by name. He remembered everyone’s name even though there were about 40 people who worked there. That’s the kind of person he is.”

Harper was not the first person taken aback by the unassuming appearance of a director who has long specialized in such strange and sensational films as Eraserhead (1977), The Elephant Man (1980) and Blue Velvet (1986). Mel Brooks, who served as the producer of The Elephant Man, reportedly referred to Lynch as “Jimmy Stewart from Mars.”

Lost Highway was a pivotal project for Harper, who was asked to create unusual cues and help contribute to the film’s overall soundscape. “Up until that point, I was really doing basic sounds: cloth movement, footsteps, whatever the characters were touching,” Harper comments. “On Lost Highway, I was now being asked to do the conceptual, and it really opened my mind to thinking and approaching my career in a different way. As a result, I have been a Foley artist who loves sound design, and I find it so rewarding.”

A native of Los Angeles, Harper attended the University of Southern California with the goal of becoming an actress. A few years after graduation, she met Foley artist Robin Harlan, who suggested that she follow her into the field. “I was mentored by her,” Harper recounts. “Robin was so helpful to me at the beginning of my career. I sat on a stage just watching her work for about a year, and then I got a job.”

The fledging Foley artist first found employment at what was then known as Concorde Pictures, run by a producer known for emphasizing economy: Roger Corman. “We had to rely on our creativity because where we were working was basically a square room with a cement floor,” Harper says. “We didn’t even have a dirt pit, so we had to bring dirt in on a blanket. I first learned to do the job with very little.”

Harper, who went on to work on such major films as No Country for Old Men (2007) and The Hunger Games (2012), says that her goal is to bring a “human touch” to soundtracks. “We follow everything the characters are doing and we represent that in sound,” she explains. “We’re walking in sync to the picture, and making sounds that can be as simple as setting a cup down or as complex as ocean waves freezing.” And her background in acting informs her work on the Foley stage. “I try to embody the characters and anticipate what they’re going to do because I am used to performing,” she says. “It’s like acting out each character with sound — you get into their walks and it just kind of comes out.”

In addition to the soles of her shoes, Harper relies on an assortment of props. “When you enter a Foley stage, you’ll see various surfaces: cement, wood, metal, dirt. There’s a water pit, and a whole kitchen with different sinks,” Harper says. “You’ll also see a corner full of chairs and a corner stacked with metal pieces. The Foley stage is filled with piles of junk. As one person said to me, the chamois is your best friend. That everyday item that people wash their cars with is a very important part of our day because most of the blood sounds are achieved using a chamois. We use it for mud. We use it for dripping. We use it for food.”

Along the way, Harper and Khuluki (her usual Foley partner at the time) had their first encounter with a member of the Lynch family: The pair were Foley artists on Boxing Helena, a 1993 film written and directed by Jennifer Chambers Lynch, David’s daughter. Harper describes the film, which centers on a character whose limbs are severed, as “very fringe,” but nothing could prepare her for out-of-the-box thinking required on Lost Highway.

“When I previewed the film, my first reaction was, ‘This is going to be fun!’” Harper recalls. “Mr. Lynch was asking for something new, and he was definitely pushing the boundary of what the audience was going to hear.

At Digital Sound and Picture, Harper — first in collaboration with Heuer, then with Khuluki — spent about two weeks working on Lost Highway. “As far as I know, [owners] Nancy and John Ross created the first fully digital facility in post-production,” Harper comments. “Digital technologies were very much needed for Lost Highway. David Lynch wanted to take the soundtrack to a different level, and we got to experiment with new ways of working.”

As a first step, Lynch and supervising sound editor Frank Gaeta participated in a spotting session, an audio recording of which was made for the Foley artists. “Frank played us a tape recording of the spotting session and then we went to work,” Harper remembers. “Normally we would do the footsteps all the way through and then we’d go back and do the props, but in this instance, we focused on the sounds that were most important to David Lynch at the time.”

Harper describes the film’s soundscape as “hyper-real” “It’s not how he uses sound — it’s almost like the absence of sound,” she says. Indeed, certain cues are heard almost in isolation. In the first scene, an unseen visitor to Fred and Renee’s house buzzes their intercom. When Fred presses a button to listen, the ominous phrase “Dick Laurent is dead” is whispered. “When Fred first goes to the intercom, there is really nothing else going on,” Harper observes. “That heightened sense of the intercom is disturbing, and we as the audience don’t know why; it’s just the click of the button or what’s being said through the intercom.”

While listening to the tape of the spotting session, Harper learned that one of the most important cues for the director came during a scene in which character named Andy (Michael Massee) hurtles toward and falls on a glass table. “He wanted to hear the sound of the air release and the blood of where his head had impacted the glass,” Harper remembers. “Frank came to me, and needed me to interpret what David Lynch meant by that. We tried a lot of things, and none of them were really working.”

In the end, Harper decided to use a ECM Omni-directional microphone. “When it’s positioned flush with a surface, it resonates in a very heightened, specific way,” Harper explains. “We put that in our ear and then we basically swallowed and pushed out air. That was the sound that ended up being used when Andy falls on the table.”

Other memorable moments for the Foley artist include a scene in which two prison guards escort Fred to his cell, with their feet echoing and keys jangling — “We added artificial ambience while we were recording it, which was new in 1996” — and a much-commented-upon segment in which Mr. Eddy has a violent skirmish with a tailgater. “I loved it that you’re getting jostled by that scene because it starts out simple and then gets really aggressive,” Harper comments. “It culminates with them out on a street and you can hear the gritty footsteps of Mr. Eddy grabbing the guy, and then there’s a blood spray to punctuate the abuse at the end.”

Harper, who now works at Warner Bros. with Foley artist Catherine Rose under the management of senior vice president Kim Waugh, was sorry to see such a challenging and creative project come to a close. “My background is performing plays in the theatre, and there’s that moment when it’s over,” she reflects. “You’ve committed so much to this and it’s been all-consuming, and then you’re finished. There’s a bittersweet feeling because you know you’ll never walk that character again.”

But the Foley artist’s Lost Highway experience lives on. “No matter what I do now, no matter what the popular movies are, if someone is a Lynch fan, they never fail to ask, ‘Oh my God! What was that like?’” Harper says. “It was such a unique experience, and I’m glad I kind of didn’t know it at the time because I might have been nervous.”