by Mel Lambert • portraits by Christopher Fragapane

In the early days of the motion picture industry, progress often required that new technologies be innovated by a studio that was advancing the art of cinema. Nowhere was this development more important than at the fledgling Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio (today the Walt Disney Company) in Hollywood, which, close to a century ago, was coming to terms with cel animation.

Later, as the need for on-hand technical specialization increased, the Disney studio developed a fully equipped machine shop, now housed at the company’s headquarters in Burbank, which opened in 1940. The shop, with its staff of talented cinetechnicians who support post-production departments by keeping their equipment up to date, is now located in the basement of the ACT (Arts/Crafts/Technical) Building, under the management of Disney’s Studio Technology group.

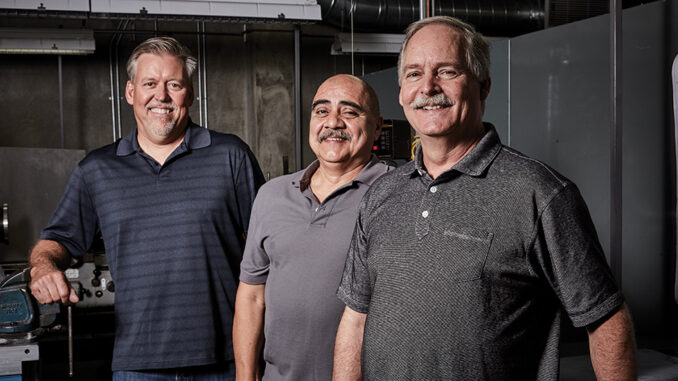

“At its peak, there were probably 120 craftsmen working here on maintenance and custom fabrication,” recalls the shop’s present foreman, cinetechnician Garry Broggie. “Now it’s just three of us — myself and my esteemed colleagues George Rowland and Daniel Quiroz.” Originally, the shop was affiliated with IATSE Local 789, and eventually transferred via Local 695 to Local 683, the Laboratory Film/Video Technicians and Cinetechnicians Guild, which in 2010 merged with Local 700.

All three of the highly experienced shop crew have been in place for several years, some more than others. Broggie joined the shop back in 1977, and this year celebrates his fourth decade at Disney; his grandfather (who worked with Walt Disney himself while building the latter’s first one-eighth-scale model train) and his father also were employed by the studio in the same capacity. Rowland joined the shop in 2015 after 30 years at Deluxe Laboratories, while Quiroz first joined Walt Disney Studios in 1980, before leaving to work at Deluxe in 1985. He returned to his current position in 2014. Together, the trio reportedly has 111 years of industry experience.

“Our shop’s primary role is to support the studio’s technical needs,” Broggie explains, “by not only looking after day-to-day care and attention, but also responding to the continuing need for new systems within the studio’s animation, picture editing and sound post-production departments.” In addition, the shop restores vintage hardware for museum displays. In the mid-1950s, the machine shop also built many of the new systems needed for Disneyland in Anaheim and additional theme parks. During the building of Florida’s EPCOT Center — the company’s theme park take on Walt Disney’s concept of an Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow that opened in 1982 near Orlando — Broggie says the crew was working in two 10-hour shifts.

“I was here from 1980 to 1985 working on systems for EPCOT Center and Tokyo Disneyland,” Quiroz recounts. “At Deluxe, I worked in the optical printer maintenance department, and was sub-foreman in the printer/electronics maintenance department for my last two years there. During the late ’90s, I was employed at Local 695 [International Sound/Cinetechnicians/Studio Projectionists] as an assistant business representative, and then as business representative at Local 683. When I returned to Deluxe, it was as on-call foreman and then sub-foreman of the printer/electronics maintenance department.”

During his three decades at Deluxe Laboratories, Rowland served as electro-mechanical technician, foreman, and research and development manager for engineering, before becoming manager of engineering, quality and reliability. “I also received a Scientific and Engineering Award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1999 for my work on the Deluxe High Speed Spray Film Cleaner, as well as a Primetime Engineering Emmy Award in 2000 for the same development,” he points out. Deluxe Laboratories closed in May 2014, due in part to the proliferation of digital projectors.

Many of the machine shop’s day-to-day fabrication projects are initiated in response to on-the-lot developments, and in close collaboration with the studio’s artists and engineers. “Our image and sound equipment is expanding rapidly as the studio adopts new systems,” Quiroz explains. “And as technologies change, we need to develop new devices.” One example is a rotatable stand with a slide-out keyboard tray that the machine shop designed and fabricated for animators who, in place of painted cels, now use touch-sensitive display monitors with digital styli.

“We are also customizing a number of computers to add USB 3.0 interfaces,” Rowland adds. “We took an off-the-shelf PCI card and fabricated a custom aluminum housing that pokes through the computer’s front panel. When completed, our design looks like it was factory-made.” The modification enables picture and sound editors to replay copyrighted video materials from external hard drives with enhanced security. To date, the shop has added the interface to a number of workstations.

In terms of fabrication, Broggie acknowledges that he picked up his skills mainly on the job, and has a machine shop at his home. He also learned welding. While Rowland is probably the most skilled electronics engineer of the trio, both he and Quiroz also have extensive experience with laboratory film equipment.

“Our engineering department here at Disney used to produce blueprint drawings for us,” Broggie says. “Now we sketch out our ideas in conjunction with the engineering department, which is managed by Andy Winderbaum, or maybe gather around our well-used white board to discuss the possibilities.”

Always cognizant of deadlines and budgets, the shop often sources components from third-party vendors. “Walt Disney Animation Studios came to us about a video monitor cart that could turn 360 degrees,” the foreman recalls. “They needed a portable cart for group meetings that could be turned to face different team members. We found a gimbal head that would support 75 pounds — more than enough for a heavy 35-pound monitor.”

“We added a four-wheel carriage with a heavy base to prevent the rig from tipping over,” adds Rowland. It was fabricated out of steel tubing, according to Quiroz, who remembers, “We welded it here in the shop and then sent it out for paint; some parts we have anodized.” A major advantage offered by the on-lot machine shop is that it can leverage existing elements in new ways, and combine them with its own fabrications to meet the needs of a particular project.

Servicing the ADR Stage

ADR Stage B at Walt Disney Studios recently contacted the machine shop about the design and implementation of two systems that, according to ADR mixer Doc Kane, CAS, and his recordist/editor Jeannette Browning Hernandez, have revolutionized their workflow and also improved client relations. “Because the positions of my microphones are critical during a time-conscious ADR session, I often need to spend a lot of time with the talent getting it just right; an inch or two either way can make a major difference,” Kane explains. “Rather than having to leave the control room every few minutes to re-position a mic — or raise and lower it when recording a loop group — it occurred to me that our machine shop might be able to devise a motor-driven system.”

“We looked at what Doc was using, and discussed how we could raise and lower the boom remotely,” Broggie recalls. “We asked him what the height range needed to be, as well as how far in front of the talent it had to be,” Rowland says. “We also asked for feedback on possible remote-control devices.”

The machine shop crew spent two weeks designing and building a standard boom stand, fitted with an electric motor that was mounted in the heavy base. “In combination with some ready-made pieces, we were able to bring the idea to fruition for Doc,” Broggie says. The team also fabricated a companion motor-driven lectern for the talent’s ADR script, using the same principle, but with a smaller motor and lead screw.

“We also fabricated a counter weight to offset the weight of two heavy studio microphones on the other end of the boom,” Rowland offers. “That way, there is a zero couple around the balance point,” meaning that the motorized lead screw runs through the system’s center of gravity with no side thrust. “The system is perfectly balanced, with less resultant wear of the lead screw and motor.”

“We defined our system’s needs during ADR sessions for the animated feature Finding Dory [2016] with [voice actor] Ellen DeGeneres,” Kane reveals. “And we first used the motorized boom on director Roland Emmerich’s Independence Day: Resurgence [2016] to record a large number of group actors, who varied in height from five-foot eight to six-foot five. As they lined up in front of the mic, I simply used the remote control’s up and down buttons to raise and lower the two mics I use until I got the result I was after. All in all, I estimate that we save around 45 minutes per eight-hour ADR session using the new system.” ADR Stage B’s custom innovation has been christened PAMS, for Precision Automated Mic Stand.

Another enhancement for the ADR stage is a performance, or “efforts,” bar that voice actors like to use while delivering lines during a dramatic scene. By being able to interact with a horizontal bar, they can reconstruct the physicality of an on-set action sequence. “We came and watched several actors at work, and took measurements of the bar layout that Doc was looking for,” says Broggie. Quiroz elaborates: “We decided to use a large flat sheet of aluminum beneath the stand, so that the actor’s weight would hold it in place.”

“I opted to use a U-shaped handle made of round bar wrapped on the horizontal section with black, non-slip rope,” Broggie explains. “We added moveable clamps down each side to provide vertical up-and-down adjustment.” Rowland adds, “To hold the horizontal handle firmly in place, we designed a pair of A-shaped side braces from aluminum extrusions. The system took us a couple of weeks to design and fabricate.”

“The efforts bar works very well, and has been used by many actors,” admits Kane, who received the Cinema Audio Society’s Career Achievement Award last year. “During ADR sessions for animated features, in particular, young actors can develop their voice character while leaning against or interacting with the bar. It’s been a major advantage.”

The crew also was involved with the design and fabrication of a custom platform for two laser projectors needed at the Pantages Theatre in Hollywood for a 3D premiere last December of Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, and this summer for the premiere of Cars 3, held in another location. “The four large projectors — two main laser units and two DLP (data loss prevention) backups — needed to be mounted on a removable platform at the back of the auditorium across several rows of seats on a terraced surface,” Broggie says. “Our rig also had to be transportable, and all the components needed to fit through a standard 32-inch door frame,” explains Rowland.

The completed rig, built from aluminum plate and extrusions, features fully adjustable legs to compensate for different seat heights. “We had two weeks to come up with a design and deliver the final version,” Broggie concedes. “Sound proofing was added to eliminate projector-fan noise for the audience.” The team is reported to have met both its budget and tight deadline.

“The entire assembly is held together with just 12 bolts, making it easy to assemble and take down,” adds Rowland. “We included sliders so that the projectors could be moved apart, as well as locking pins to align them on site.” The locking pins also prevent the projectors from moving off the platform.

Other machine shop custom projects around the Disney lot include a 20-foot video monitor rail bolted to the rear of the AMS-Neve DFC digital console in Stage C, to provide flexible positioning of the dozen or so picture and sound workstation screens needed during a re-recording session. The shop also fabricated custom brackets for the stage’s various surround-channel loudspeakers mounted on the walls and ceiling as part of the room’s Dolby Atmos immersive sound system.

In many ways, the machine shop is rather like a big Erector Set, with access to stocks of metal and plastic plates and rods, as well as assembly parts. “We have a large selection of different materials,” Broggie confirms. The shop also features several lathes, mills and fabricating equipment. “We can turn our hand to just about anything,” the foreman claims — “including the restoration of two animation camera stands that eventually will be used for historical displays.”