by Michael Kunkes

In the beginning, as with so much of Hollywood, there was Paramount. Hollywood’s oldest studio’s stock footage library came into existence in the mid-1920s, the accidental invention of Hazel Marshall, a negative cutter who joined the studio around 1926. Michelle Davidson, head librarian of the studio’s feature film stock library, says that the idea really came into favor with the increase in B-movies and second features in the 1930s.

“Hazel started getting requests from Paramount producers for ‘leftover’ trims and outs from locations that appeared frequently in releases,” Davidson says. “She had already been saving Paramount trims from as far back as 1924’s Song of Songs. She developed the idea that you could have an entire collection of outtakes to service production, and came up with many of the principles of stock that we still use today—having original negative rolls to match a piece of film, proper storage and cataloguing, selling to other studios and outside producers, and the idea of selling a minimum of ten feet of footage [which later evolved into ten seconds in the video age]. This all came from Hazel.”

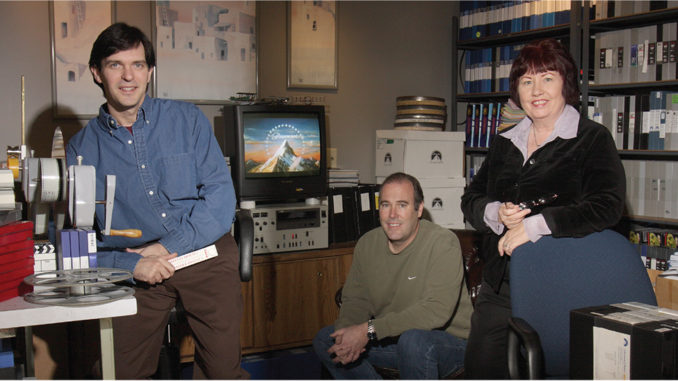

As much as anything else created at a studio, stock footage is intellectual property. The studio owns the copyright and can license the content as it sees fit. The purpose of a stock footage library and, by definition, the job of the Editors Guild classification of librarian, is to catalogue and preserve all trims and outtakes from studio productions, with the specific idea of repurposing the content in new media, servicing the studio’s own productions and “monetizing” those assets—selling to other studios, independents, ad agencies, corporate and industrial producers, web companies, filmmakers, students and schools. “Stock footage has never appeared in the final picture; stock is all trims and outtakes, never completed negative. It’s an important distinction to make,” adds Davidson, who is aided in her department by librarians Steve Ellena and Rob Vaughn.

For the majors, whether or not to develop a stock footage library has always been a business decision. Some studios, such as Disney, MGM and Universal, have shuttered theirs as a cost-saving measure (though they still employ librarians); others, such as Fox, Warner Bros. and Paramount, saw the potential return on investment from maintaining a stock library.

On the completed products side on the Paramount lot, head librarian at the CBS Archive Building, Robert McCracken, notes that over 2,000 elements each day move in and out of the Paramount infrastructure, which also includes a second vault of duplicate elements in their original native formats in limestone vaults on the East Coast––a safeguard against catastrophe.

Not that there’s much chance of that happening. In the Los Angeles vault, a custom facility built behind the famous studio moat, emulsion material is stored at 40 degrees F, sprocketed magnetic material at 50 degrees and magnetic materials at 70 degrees––all protected with fire suppression systems. Says McCracken, “The vault is the core of our worldwide asset protection program, and having a stable, steady environment is very important to keep items from expanding, contracting, twisting––or otherwise physically damaging themselves, along with maintaining color dyes.”

As libraries modernized, they abandoned the rolodexes and 3-by-5 cards that had served them for decades, and created proprietary studio software to compile and supply as metadata each piece of information known about the trim—show numbers, key numbers, show titles, camera roll number, shoot date, etc., along with a keyframe from the trim. For example, at Paramount, a system called OPIS [Operations Inventory System], constantly updated and versioned over 20 years, keeps track of the completed products inventory, divided between feature and TV element (a separate database handles the stock footage inventory). “We have over 600 users worldwide,” explains McCracken, who supervises a staff of 18 librarians, vault and shipping crew. “Users can access footage by title, purchase order, version, audio configuration, etc. They can find out where elements are stored, as well as an entire history of where it’s been, when it was last supplied, who signed for it, etc. It’s an amazing system.”

Focus on TV Footage

At 20th Century Fox, the stock footage library has been servicing producers since the late

1930s, and currently inventories about 60,000 elements, largely on-site. According to head librarian Wendy Carter, the studio is focusing lately on building its TV stock library, mainly due to an increased demand for high-definition or film negative clips. “When it comes to building up stock footage, we’re all in the same boat, because that’s the nature of film; no one wants to spend a lot of time and money transferring material that people aren’t really asking for,” she says. “We’re doing a good job of servicing our shows, such as 24, Women’s Murder Club, Boston Legal, Prison Break, Shark, Bones, My Name Is Earl, etc., by cataloguing the material as soon as we can after it’s shot, so that it’s available for future episodes or for new shows after those are discontinued.”

J.P. Perches, who has been working in film libraries since the age of 15, joined Carter at Fox last summer from Warner Bros., and the two are working on outside sales. “The business is becoming so streamlined, we’re able to handle our shows very quickly, which is what they want,” Perches explains. “We don’t even need drivers anymore, because we can just stream bins over.”

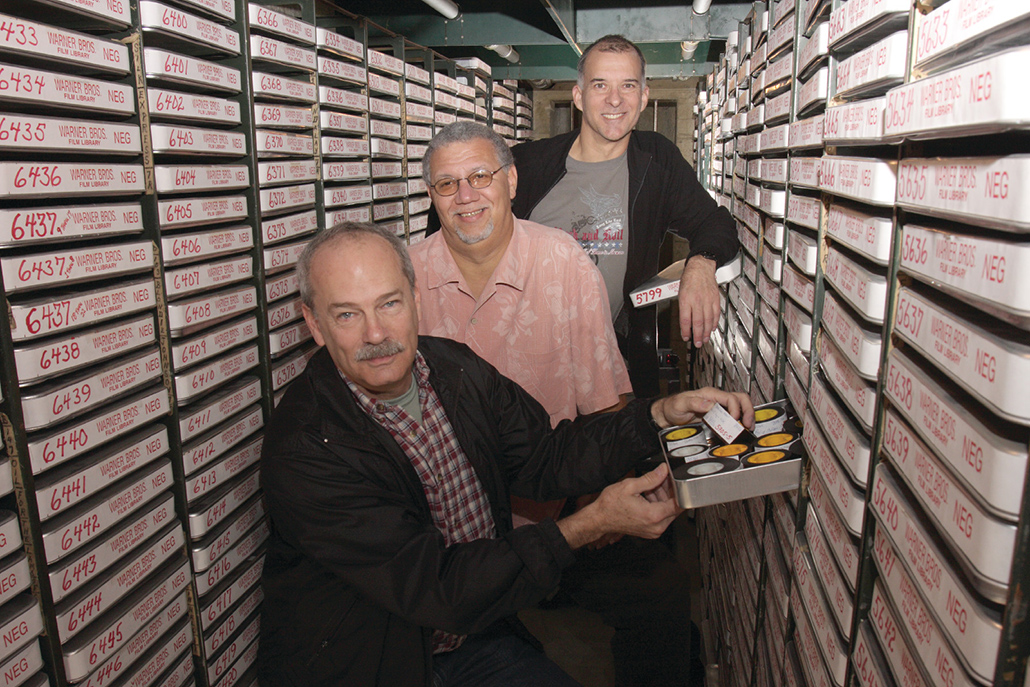

Donald Wylie, head librarian at the Warner Bros. Feature Library, was able to supply an exact number of assets of all kinds, TV and feature—122,420—in the library on the day he spoke with us. The Warner Bros. Feature Library dates back to 1939, with the archiving of Technicolor trims from Errol Flynn’s Dodge City. “They didn’t want to have to keep building a new town,” Wylie laughs. True enough; compare that footage with Flynn’s 1945 San Antonio: same town, same scene––a story repeated at every studio. “Here at Warner Bros., the storage facilities are also about the same as they were then, built in the days of flammable nitrate stock. “The walls are so thick and strong, with firewalls and inner metal doors, that the temperature stays consistent all year round.”

Wylie, who once worked for the late Guild past president Bea Dennis at her own stock library in the 1980s, describes the process of stocking a feature library. “When a librarian gets a title that’s been made available for stock, we see everything the picture editor looked at––sometimes as many as 200 tapes per film. From there, it’s at the librarian’s discretion what we want to keep as stock, before it goes up on Warner Bros.’ MARS (Media Asset Retrieval System). We look for any kind of establishing shots––cityscapes, aerials, animals, locations, street scenes—whatever hits the gut as a good shot; the more generic, the better. This enriches our content endlessly,” says Wylie, whose staff also includes librarians Bruce Miyagishima and Aaron Smith.

On the TV side, Bob Mead has been head librarian for the Warner Bros. TV Library since 1994. His staff includes librarians Mark Wilson, Yuell Newsome, and Matthew Peerce (grandson of opera singer Jan Peerce and son of director Larry Peerce). “The plain truth is that we all sell footage to each other because of the sheer volume of shows and features being produced each year,” Mead says. “The chances of finding the shots you need are much better with the majors, as opposed to one of the smaller independent libraries that just don’t shoot as much, or have the access that we have.”

Although the procedure varies from studio to studio, HD and 35mm negative are the most current media delivery methods. “If we have an HD master, we’ll clone the shot and send it on a physical master––but a lot of people prefer to use the original negative,” explains Paramount’s Davidson. “We’ll prep the neg and send it to the lab to be scanned for the digital intermediate or telecined to a TV show’s stock reel. Sometimes, we’ll post shots to an FTP site, but most customers prefer to have the physical media. That is changing, though, and we are moving toward a goal of delivering all media as digital files.”

Damian Begley, a Guild Board member representing the Eastern Region (and son of one-time Local 771 Sergeant-at-Arms Peet Begley), is one of a team of tape librarians at the NBC Central Archives in North Bergen, New Jersey. The other librarians are Bernie Robinson, Chris Vacca, Gralin Hilton, Ted LoBlanco and Russ Manley. The facility is home to hundreds of thousands of tapes of NBC News footage, going back to the very first Meet the Press in 1947.

According to Begley, the work is divided between internal servicing of NBC Nightly News, The Today Show, Countdown, Hardball and others, and sales to external purchasers. Either way, the process of search and delivery is about the same. “The researchers at 30 Rock call us here with tape requests; the more detail they put into the request, the better the cross section of tapes they get back from us,” says Begley. “We pull the tapes, scan them out, package them and send them off to 30 Rock or CNBC in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey on one of many scheduled cab runs each day into Manhattan. When we have a film request, we send it to chief librarian Joyce Nakamura at the NBC Film Library in New York.”

Begley and the team also function as a rapid response unit. “Another part of the job is to feed tapes,” he explains. “The process is similar to a regular order, except that because of a tight deadline, we’ll call satellite operations, then feed the tape to an external source for downlink to any affiliate, anywhere in the country. We’ll process as many as two-dozen feed orders a day––in addition to the 100-plus regular orders that go to 30 Rock each day.”

A Dirty Job?

Eric V. Smith, who works in the Warner Bros. TV Archives with assistants Rodney Dorsett and Ronnie White, calls himself the “Dirty Harry” (a Warner Bros. property, of course) of the department. “Librarians don’t like to get dirty,” Smith jokes. “When they need to find something, they call me.” Sometimes that pays off. Recently, Smith and his apprentices went to clean out an old vault on Seward Street in Hollywood.

“We put on our gloves, went in there and found a room packed to the ceiling with old 16mm acetate prints, all breaking down and smelling of vinegar,” Smith recalls. “We found a 16mm can with an episode of the short-lived [eight episodes] James Stewart Show dramatic series from 1971. We couldn’t believe this was for real.” Smith adds that, in general, “Editors for all Warner Bros.-produced shows rely on us to get them anything they require during the course of a production. When we get a call, we’ll send them material with one of my apprentices, or we’ll send a driver––on- or off-site––from either our vault or from a couple of warehouses we maintain around town.”

Plenty of other vault stories abound. When Paramount reissued Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard on DVD in 2002, the original opening, which showed William Holden’s body on a slab in the morgue with his disembodied voice addressing the other corpses, had been thought lost. Davidson and her staff were able to supply the original material, which had been stored in the library.

On another occasion that same year, when Roman Holiday (1953), was being prepared for DVD reissue, it was decided to remake the title sequence in order to properly credit blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo and remove Ian McLellan Hunter, the credited—and Oscar winning—writer. “The textless backgrounds for the titles had been lost,” Davidson recalled. “But we had all the outs from the second unit that had been in Italy, and they were able to re-create the titles, shot for shot, with Trumbo’s name. What we’re able to do with these resources is invaluable.”

For the majors, whether or not to develop a stock footage library has always been a business decision. Some studios, such as Disney, MGM and Universal, have shuttered theirs as a cost-saving measure [though they still employ librarians]; others, such as Fox, Warner Bros. and Paramount, saw the potential return on investment from maintaining a stock library.

Fox’s Perches recalls a story in connection with the in-progress restoration of the documentary Woodstock (1970). “When the Northridge quake hit in 1994, all the 16mm footage of Woodstock—dailies, trims and workprint—fell down, and then got rained on when the sprinklers went off,” he recalls.

“People just shoved it back into boxes and no one knew where anything was. Four years ago, we found about 36 miles of 16mm footage and sound rolls, and none of it matched. It was our job to go through it all, roll by roll, and tell the studio what they had. That’s the value of librarians who know how to handle film. You can’t replace that experience.”

A Skilled, Gloved Hand

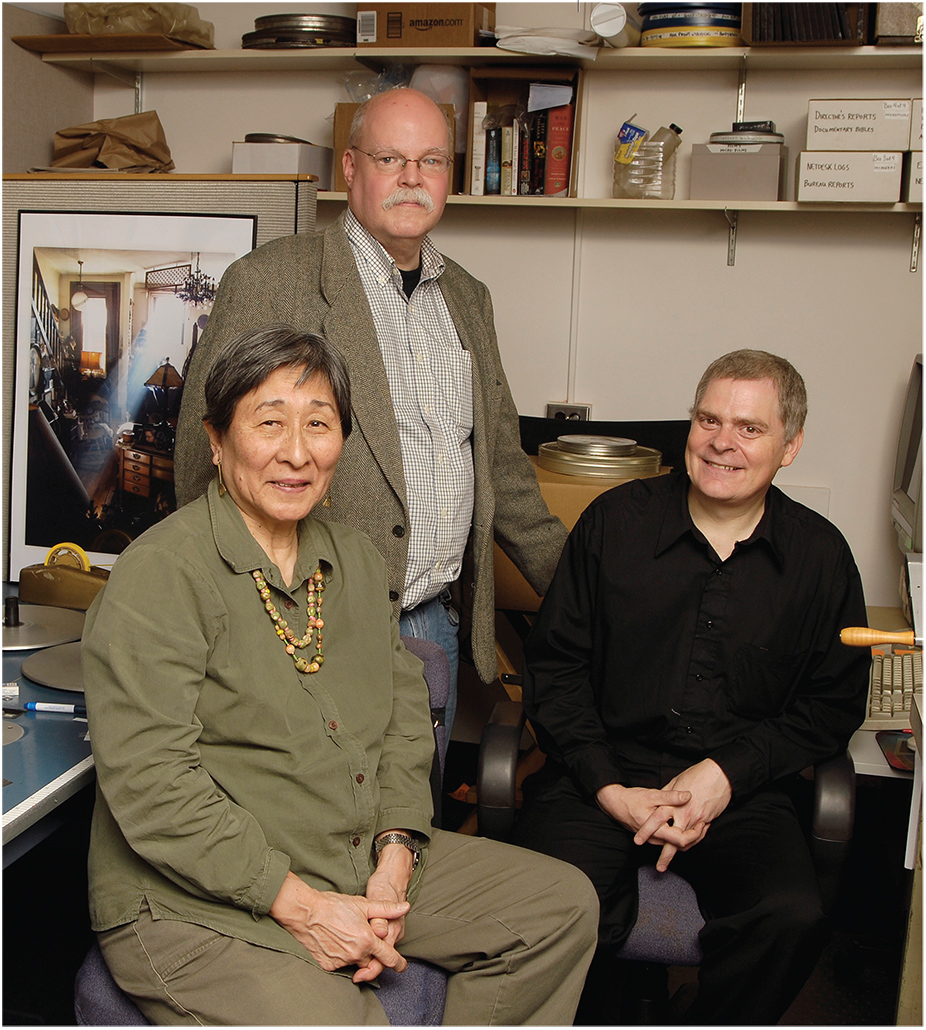

Harry Peck Bolles would agree with that assessment. At NBC, Bolles, who, like Begley, represents the Eastern Region on the Guild’s Board of Directors, works alongside head librarian Nakamura at the NBC film stock library at Rockefeller Plaza, where 95 percent of the library services are film-based––the opposite of the North Bergen facility. “The skill I bring is familiarity with film handling,” Bolles says. A skilled, gloved hand is a necessary requirement in dealing with old news footage, which he feels has often been mistreated.

“This is not the kind of material I experienced in my years as an assistant,” Bolles continues. “It’s been pretty roughly handled. News producers in those days weren’t really interested in trims; what they cared about was turning 300 feet of film into 72 feet for a news story. The condition of these trims sometimes makes me curse these assistants from the past––but the truth of it is that they were doing a different job altogether.”

Looking ahead, Warner Bros.’ Mead sees a very strong future for the studio libraries that have stayed in the game. “Shows have become so reliant on stock,” he explains. “People aren’t just looking for a New York skyline shot; now they are looking for playback material for TVs and monitors––elements with unique camera moves that they can build effects with; even material for YouTube videos. Anything and everything is available.”

“People were saying that librarians weren’t needed anymore,” says Paramount’s Davidson. “But the entire world of stock footage has taken off, thanks to an ongoing explosion of available content. Improvements in workflow, search technology and delivery methods are making our jobs even more valuable. It’s a huge world out there, and the studios are still tapping into it.”