by Anthony Carbone

The first movie I remember seeing was Friday the 13th. I was five, and my parents thought this would be a perfect night out for the family. So off we went to the dusty drive-in. I remember the inky Utah night surrounding our Fiat as I stared at the flickering drive-in screen, loving every minute of it.

From then on, I gobbled up every movie I could. As the video age came along, I made my Dad rent me whatever caught my eye. Those movies had one thing in common: they were all escapist, mindless eye candy. And that’s what I thought films were for. As the years trickled by, nothing I saw would change that view—until I watched The Graduate.

That was three states and a dozen years later when, at the start of my junior year in high school, my father moved us from Maine to Connecticut. Having no friends, I spent a lot of time in the town library. One day, I stumbled upon a large shelf of videos. Scanning through, I was delighted to see all my favorites: The Goonies, Young Sherlock Holmes, etc. But mixed in with them were films with strange foreign titles and bland, black-and-white covers.

I avoided those and went straight for the candy. Eventually, having watched The Monster Squad at least 12 times, I ran out of movies that I wanted to see. There was only one thing to do—rent an old movie. I picked The Graduate. Why? Its cover was in color, the picture was of a young Dustin Hoffman staring at that famous sexy leg. I liked him in Hook, plus the back of the video said it was a comedy. Add to that the promise of possible nudity, and I was sold.

Seeing all these things work together for the first time, I realized that movies could be an art form.

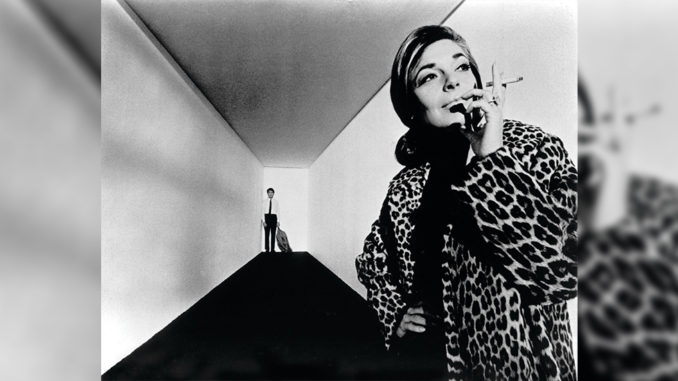

Hoffman stars as Benjamin Braddock, a recent college graduate who has no idea what to do with his life. The film opens on a party his parents have thrown for him, attended only by their friends. It’s clear that Benjamin feels out of place. Eventually, his father’s business partner’s wife asks him to drive her home. This is Mrs. Robinson (the beautiful Anne Bancroft). When he gets her home, she coaxes Benjamin inside, lures him into the bedroom, and tries to seduce him. Benjamin flees, but not before she makes it clear that if he wants her, he can have her.

After a few days pass, Benjamin decides he does want her, and their secret affair begins. His parents grow concerned as they watch him listlessly drift through the summer. Eventually, they force him to go out on a date with Mrs. Robinson’s daughter Elaine, (Katherine Ross). To his surprise––and to the fury of Mrs. Robinson––he likes Elaine enough that he ends things with the mother and starts to pursue the daughter. A lot of hilarity, heartbreak and chaos ensue, including the famous ending where Benjamin does whatever he can to stop Elaine from marrying the wrong man.

When the movie ended, I was floored. I related perfectly to all those moments of Benjamin feeling alone, at odds with the world. But it wasn’t only the script or the characters that made me feel that way, it was the film––every single element of it: the cinematography, the sound and the haunting music of Simon and Garfunkel that propelled each montage forward, giving scenes a sense of despair and loss. Even the editing (by the great Sam O’Steen). There is a moment in one montage where Benjamin is swimming in a pool. He stops at the edge and pulls himself out, and with one deft edit, the perfect graphic match, he lands into bed with Mrs. Robinson. That never happened in The Monster Squad.

These were elements I had never noticed or cared about before. But seeing all these things work together for the first time, I realized that movies could be an art form. After The Graduate, I went back to the library and rented every film down the line––even the black-and-white ones. I was awed by 2001 and put in a state of despair by The Bicycle Thief. Movies were candy no more.

Nowadays, I still have a soft spot for films filled with empty calories, but the movies I really love aspire to more. They use every filmmaking tool to move audiences—not just to tell them a story, but to make them feel it. You can find me sitting in a darkened theatre, staring at the flickering screen and still loving every minute of it.