by Kevin Lewis

Before the major studios of the sound era existed, there was actually the giant Vitagraph Studio, which was built 100 years ago. It was the veritable cradle of the film industry roughly comparable to Henry Ford’s revolutionizing of the auto industry with the assembly line. Its Flatbush, Brooklyn studio was the model and forerunner of the studio system. Vitagraph was also at the forefront of the development of sound after it was acquired by Warner Bros. in the mid- 1920s. Today, the site marks the only place in the United States and perhaps the world where editing has occurred continuously for a century.

While the Fort Lee, New Jersey studios of Fox, World, Goldwyn, among others had been leveled long ago, and American Mutoscope and Biograph, the Manhattan studio where D.W. Griffith made his films, is now an apartment complex, the old Vitagraph Studio building is still in use as the Shulamite School for Girls. The studio across the street, built by Warner Bros. in the late 1920s, is now JC Studios, where As the World Turns is produced. So if Vitagraph can have any vindication, it has survived. Though the site is not landmarked, to film historians this is hallowed ground.

Unlike other historical writing, film history abounds in contradictions and falsehoods. The history of Vitagraph and its adjacent buildings has been disputed by film historians, but what follows is as close an approximation as this writer can achieve.

English newspaperman and cartoonist J. Stuart Blackton, who wrote for The New York World, interviewed Thomas A. Edison, the inventor of the Kinetoscope, in 1896. Edison liked his drawings so much that he made a film starring him called Blackton, The Evening World Cartoonist (1896). Blackton and his partners Albert E. Smith and Ronald Reader were intrigued by the nascent motion pictures, so they bought equipment from Edison and filmed their first production on a Nassau Street rooftop near City Hall in downtown Manhattan in 1897. Appropriately, this maiden production, The Burglar on the Roof, was a crime drama, a genre that is still the bread and butter of the film industry.

The year after, Blackton and company faked a military endeavor, the Battle of Santiago Bay, for the film Tearing Down the Spanish Flag (1898), making what film historian Ephraim Katz calls “the world’s first propaganda film.” Katz also credits Blackton with inventing the close-up and pioneering single-frame animation for his cartoons. Like Griffith, he emphasized film editing, especially noteworthy in his Scenes of True Life series, a realistic group of films he directed beginning in 1908, Katz wrote.

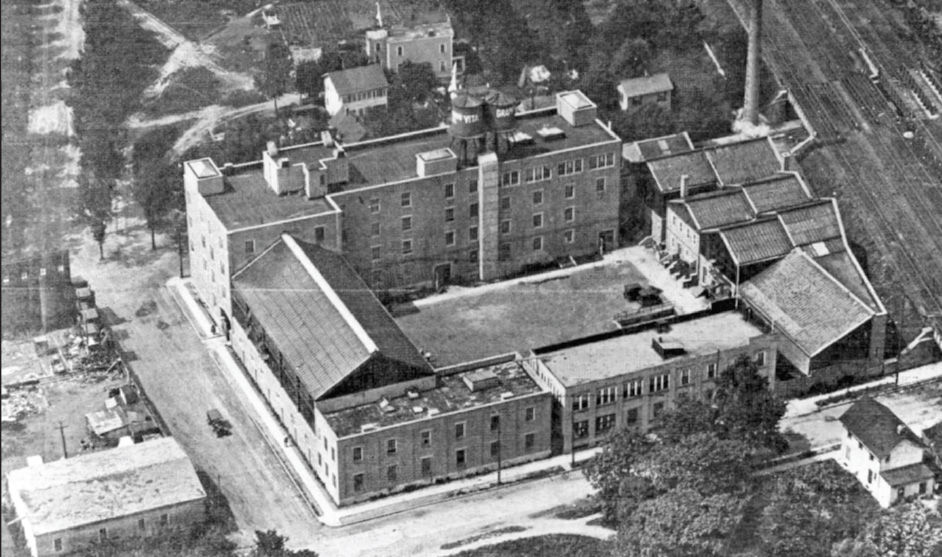

Blackton and his partners were so successful with their early films that they bought land in then semi-rural Flatbush, Brooklyn and began building the Vitagraph Studio in 1905. The name was a nod to the Vitascope, Edison’s patented early film projection equipment. (Not honored by the homage, Edison sued successfully for royalties for use of the moniker.) Vitagraph opened in November 1906, between E. 14th Street, Avenue M, E. 15th Street and Locust Avenue in what is now the Midwood section of Brooklyn, it was a marvel. Blackton produced the first animated film, Humorous Phases of Funny Faces, there that year.

To call Vitagraph an innovative studio would be an understatement because there was no precedent. Its competitors, American Mutoscope and Biograph and the Edison Company, were primitive by comparison and out of business within a few years. Vitagraph boasted the first glass-enclosed studio, a studio tank for battle and sea scenes, costume and set design shops, vast editing and processing rooms and lavish sets. Historical spectacles such as Washington Under the American Flag (1909), drawing room farces featuring Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Drew, slapstick comedy with John Bunny, literary classics like A Tale of Two Cities (1911), and religious epics such as The Life of Moses (1909-10) were filmed here or at the beach in nearby Coney Island. The Life of Moses was truly ahead of its time; it was filmed in five reels before feature film production even began around 1912.

Vitagraph helped inaugurate the star system and the movie magazine. In 1911, it published the first movie fan magazine, Motion Picture Story Magazine, and groomed such stars as Bunny, Mr. And Mrs. Sidney Drew, Norma and Constance Talmadge, Anita Stewart, Clara Kimball Young, Flora Finch, Maurice Costello and Mabel Normand. There were over 100 players in the studio’s stock company.

Unfortunately, however, Blackton and his partners were not prescient enough to associate their studio with a theatre chain. Their competitors in the 1913- 1919 era realized that they needed theatre chains to show their productions and, in fact, to survive. Famous Players- Lasky, owned by Adolph Zukor and Jesse Lasky, had the Paramount Theatre chain behind it. Marcus Loew of Loews Inc. bought the Metro, Goldwyn and Mayer Studios to produce films for his theatres, and theatre mogul William Fox founded Fox Film Corporation.

By the early 1920s, Vitagraph could not find screens on which to show its movies and in 1925, Blackton sold the studio to Warner Bros. (then only two years old,) which used the Flatbush studio for its sound experiments with Western Electric (Bell Laboratories) to produce Vitaphone synchronized sound shorts and music scores for feature films, of which Don Juan (1926) was the first. And, of course, there was the biggest theatrical attraction of its day The Jazz Singer (1927), with which Al Jolson launched the feature film talkie revolution. Warners already had a theatre chain, which it acquired when it bought First National Studio, and early on equipped the theatre with sound equipment.

Though the early Vitaphone films were recorded at the Manhattan Opera House or the Warner Bros. Studios in Hollywood (also formerly Vitagraph), the Brooklyn studio was refurbished in 1928 to produce sound films. An East Coast studio was necessary in those early days of sound because the Vitaphone shorts featured vaudeville artists such as Burns and Allen and Metropolitan Opera stars such as Giovanni Martinelli, who would not travel to Los Angeles.

Warner Bros. built an adjacent studio across the street from the Vitagraph Studio, but it was constructed during the 1928-30 period. Warners sold this newer property around 1952 to NBC, which produced many television specials at the studio, including one of the most famous TV shows, starring Mary Martin in 1960.

From 1934 to 1959, Warner Bros. used the Vitagraph Studio for its Ace Film Laboratory. However, it was sold in the early 1960s to Yeshiva University High School for Boys and Girls. The school opened in 1965 and was sold by Yeshiva in 1980 to the Shulamite School for Girls, which still occupies the site. Older Yeshiva students recalled in 1990 that the gymnasium boasted Vitagraph artwork on the ceiling. All of that has since been covered over by Shulamite School, but fortunately the smokestack in the parking lot, which still has the black brick letters V-I-TA-G-R-A-P-H down its side, remains as the only hint of this site’s historic past.

The adjacent studio bought by NBC housed sets for the network’s daytime drama Another World until it ended its long run in 1999. In 2000, JC Studios bought the studio from NBC and Proctor & Gamble moved its legendary As the World Turns daytime series from CBS Broadcast Center on 57th Street in Manhattan (where it had been produced since 1956) into the studio. Both production and postproduction of the longtime soap opera have been done there since. So, it’s a double anniversary in 2006 for this historical site. The original Vitagraph Studio celebrates its centennial, while As the World Turns turns 50.