by Kevin Lewis

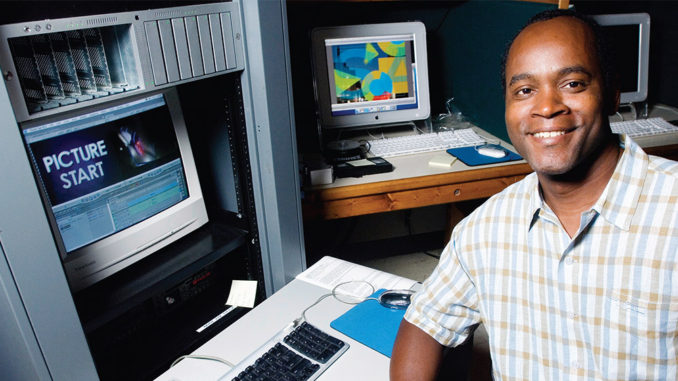

After a decade of editing films at Spike Lee’s 40 Acres and a Mule, Leander Sales decided to instruct others in the craft. He stepped outside the industry to teach editing at the North Carolina School of the Arts (NCSA) in his native Winston-Salem. Sales, who evolved from apprentice to assistant to full-fledged editor on Lee’s films, initially worked under editors Barry Alexander Brown (see accompanying story) and Sam Pollard, until he became the editor of the director’s documentary Get On the Bus (1996). He also edited three music videos directed by Lee in the early 1990s.

Sales became interested in filmmaking after moving to Italy in the 1980s, where he saw films at the many festivals there. He had originally intended on becoming an actor, after training at the NCSA, following in the footsteps of his uncle, noted actor Ron Dortch. Instead, the films of Fellini, Rossellini and Visconti that he watched in the language school he attended changed his destiny. Sidney Poitier’s autobiography, This Life, was also an influence, especially the actor/director’s thoughts on the filmmaking process.

“Poitier wrote that the best place to learn how to make a film is in the editing room, because you learn what gets used and what doesn’t get used in the storytelling process,” Sales recalls. “I thought, ‘Wow, that’s just where I want to be,’ because when I really started thinking about editing and talking with people, it was clear that editors dealt with everything––cinematography, sound, actors’ performances, all of that.”

When he returned to New York in 1987, Sales contacted his uncle, who introduced him to the sound editor Rudy Gaskins, a friend and classmate of Lee from New York University. Gaskins in turn referred Sales to Lee, who hired him for a four-month job as an apprentice sound editor on School Daze (1988). It was an especially lucky break for Sales because of his admiration for Lee’s first film, She’s Gotta Have It (1986). “That film was like a breath of fresh air,” he says. “I had never seen anything like it; it just blew me away.”

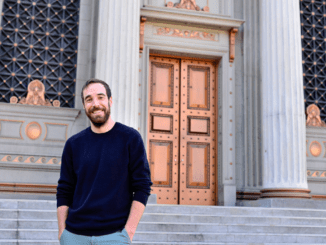

Leander Sales and his class hold teleconferences with editors who are working in Los Angeles or New York.

Sales served as apprentice film editor on Do the Right Thing (1989) and was impressed to be working with such a diverse crew. “When you look at all the other crews––how diverse are they? Here you are with Wynn Thomas, production designer; Ernest Dickerson, the DP; and all these other people of color. As I look back now, it was really a special time, because you don’t see that a lot.”

As an apprentice, he worked first for Lee’s editor, Brown. “I got promoted because I was on time every day,” he recalls. “It taught me to be on time because you never know who’s watching. And be ready to work late; a lot of the time you have to.” Now that Sales is a teacher, he impresses this advice on his students: “It says you care when you are on time. If you’re on time, people want to teach you.”

Sales was an attentive pupil, learning all he could from Tula Goenka, Brown’s assistant at the time. “I also learned a lot from Barry and editor Sam Pollard,” he says. “They have two different styles––and that’s what I liked––I could take something from Barry, something from Sam and mix them in with my own sensibilities.” In fact, it was Pollard who gave him a chance to cut for the first time. “Sam gave me latitude and didn’t sit with me,” Sales explains. “It was a way of saying, ‘Okay, I’m going to see if you’re really paying attention, pal, while you’re sitting next to me all day.’ I feel like I started at the top when I started editing. I had to go back and learn how to cut 16mm.”

His favorite part of editing is putting the performance together. “You’re watching the ‘human’ being born,” he says. “My first love in filmmaking is great acting, because that’s my background. Denzel Washington and Delroy Lindo were amazing in that scene where they first meet in Malcolm X, as was Thomas Jefferson Byrd in Clockers.

Sales particularly enjoyed working as an editor with Lee. “Spike really lets the editor be creative, and he’s not afraid to try something different,” he attests. “He thoroughly understands the editing process because he edited his earlier films; She’s Gotta Have It knocked the ball out of the park.

“The best place to learn how to make a film is in the editing room, because you learn what gets used and what doesn’t get used in the storytelling process,” – Leander Sales

“Whenever I wanted to try something different, Spike would just say, ‘Go ahead,’” Sales continues. “After viewing the new cut, he would either give his approval or give you the head shake––which could mean many things. It could mean, ‘Hell, no,’ or, ‘It’s not quite there, but keep cutting.’ The great thing about this process is that it gave me a sense of direction.”

Sales also appreciated the independence that Lee grants his editors. “He trusts his editors enough to let them find the rhythm of the performances and the uniqueness of the story from their own perspectives; Spike likes to be surprised,” he says. “Because editors view the footage so much, we try to find ways to tell the story without calling attention to the editing. That’s very tricky.”

Lee gave Sales his first shot at being an editor on several music videos. “My favorite video I did with Spike was for Fishbone’s “Sunless Saturday” [1990]. You don’t see those kind of music videos today. I was like a kid in the candy store with that one, but I also had a great assistant editor––Anthony Jamison––who worked all night keeping everything organized, because that one was cut on film using the Steenbeck.”

After having worked as an apprentice and an assistant on Lee’s films, Sales knew that his videos were not going to be the typical music video editing experience. “You’re not going to see a lot of ‘bling bling’ and fancy cars and girls shaking what the good Lord gave ‘em,” he explains. “I felt really free cutting the music videos––but there was also pressure to get it done quickly because the schedule is always tight. Spike was more relaxed, however. He grew up with musicians and you get a sense of it when working on his music videos.”

Sales also directed his own film, Don’t Let Your Meat Loaf (1995), which was the first place winner in the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame Film Festival in 1995. In 1998, he stepped away from editing regularly to begin teaching the craft as a filmmaker-in-residence at the NCSA, and is currently producing and directing a film, Jazz It Up, in Winston-Salem. But he does not feel out of the loop because, “You can make films anywhere with the technology today. While he personally uses Final Cut Pro––mainly for cost purposes––he teaches the technology of the Avid system and cutting on film.

“I got promoted because I was on time every day,” – Leander Sales

Although North Carolina boasts a major film studio in Wilmington and a comprehensive filmmaking program at NCSA, it is a right-to-work state that discourages union activity. Because of its agreements with guilds and unions, the film industry is not supported by the state legislature in Raleigh. Sales expresses his disappointment in that fact, adding, “But take other states where films are made––Louisiana, for example––they take a different, pro-union approach, and more people are going there to make films.” But non-union films are still being made in North Carolina, he acknowledges.

Sales joined the Editors Guild in 1988 at the urging of his colleagues at 40 Acres, and the Guild remains very important to him, a belief he impresses upon his students. “When I tell them how I joined the union––and its importance––I give them the story of how there were no people of color when I joined,” he explains. Sales and his class hold teleconferences with editors who are working in Los Angeles or New York. “The students hear different parts of the whole story of being union,” he says. “What does it mean to be part of the union? We have some people who graduated from the school and worked on films like Seabiscuit, and they talk about how important it is to be part of the union.

“Then we have people who are working in reality TV, where you have 12 or 14 editors on a show and it’s more possible to get a job than on feature films where there’s only one editor,” he continues. Unfortunately, Sales adds, if they take those non-union jobs, they are not going to get benefits, health insurance or a union pension.

A textbook example of a fledging editor––who was given a lucky break––later “paying forward” by sharing his knowledge, expertise and advice as a teacher, Leander Sales has taken a cue from the title of one of the early films he worked on: Do the Right Thing.