Editing in the world of Reality Television is nothing like editing scripted drama, comedy or MOWs in television. It’s not the craft that’s dissimilar; it’s the approach, terminology and producer structure.

As a picture editor whose resume includes over 25 years of scripted TV shows, I was amazed to discover the difference. There are no egos in the cutting room as the concept of a free and collaborative team takes over in Reality TV.

There is no script, so editors are given the opportunity (and difficult task) of helping to create the story. This results in greater respect and higher pay for some editors in the Reality world.

Reality TV has given birth to a new job title––the “preditor”––created from merging the words producer and editor. A preditor is an editor who helps sculpt the story, and the title is gaining popularity.

At the Hollywood Radio and Television Society Luncheon in December, the panel of experts said that the genre of Reality is nowhere near dead. Based on the 2004 Nielsen ratings, on any given week, two to three Reality shows are in the top 10 of the highest nationally rated shows. For the week ending December 12, eight of the top 25 shows were Reality programs. The one-hour Survivor just finished its ninth season, yet continually places in the top five of national rankings, confirming that Reality franchises like Survivor and The Amazing Race are thriving.

Sure, there are Reality flops that get yanked rapidly off the air, but don’t be fooled just because a few Reality shows post declines in ratings or fail; the genre is still very viable. And yes, some Reality shows are degrading and insulting to our intelligence, but unfortunately Reality doesn’t hold a monopoly on lousy programming. Regardless of your personal feelings about Reality Television, it’s undeniably high time that it has been taken seriously from a career and business standpoint.

This article will cover the ins and outs of Reality editing, including technical details. Nothing is gospel because as the format evolves, things change. The goal is to enlighten––and to supply enough information for an editor or producer to start work and hit the ground running on Reality shows like America’s Next Top Model, The Bachelor or Big Brother. We’ll also cover Reality terminology, including “pods,” “logs,” “selects,” “string-outs,” “Frankenbites” and more.

Reality Show Categories

One top-rated Reality show in town has a Unity hooked up to 12 terabytes (12,000 gigs of storage) and 28 Avids! The type of Reality show (yes, there are types,) determines the amount of dailies to expect and the number of editors required, so let’s categorize them generally.

What we call semi-scripted shows––like Joe Schmo or My Obnoxious Fiancé–– may have some contestants that are actors who ad-lib alongside non-actor contestants. These shows have pre-determined scenes and/or times of day when they plan to be shooting and do not have cameras running ‘round the clock.

Date shows like The Bachelor or Average Joe shoot more footage but have definite formats and segments (aka scenes) that occur in every episode, such as challenges, dates and elimination ceremonies. Very rigid format shows, such as Who’s My Daddy (about adopted women choosing their father out of eight contestants), have the least amount of dailies because the contestants must be kept apart; therefore filming times are pre-determined and limited.

Reality shows that follow the contestants 24/7 such as The Apprentice, have the most amount of dailies and 80 or more hours per day is normal. As with scripted television, it would be wise to find out the type of Reality show before you accept a job and agree to a post-production schedule.

Good-bye Gigabytes, Hello Terabytes

A typical scripted one-hour drama with a seven-day shoot might average 40 minutes per day of dailies. Compare this to a drama like Magnificent 7, an hour series with seven cowboys, where two hours of dailies per day was common. Medical dramas like Strong Medicine or ER occasionally get five hours per day. So, as an all-inclusive average, let’s say that an editor on a scripted one-hour drama can expect seven-to-35 hours of dailies per episode.

Well, hang onto your hat. On a one-hour non-scripted Reality episode you can expect 40-150 hours of dailies in one day! A show with a rigid format might shoot only 35-50 hours in one day, whereas the first episode of a new series with lots of contestants could have 150 hours. A show with cameras in the living quarters shooting ‘round the clock like Paradise Hotel can even have 225 hours per day.

Every time an editor of Reality starts an episode, it’s like starting an aggressive hunting mission because he or she has to search through a jungle of footage looking for some semblance of a story. It actually can be quite fun and creative.

Interestingly, Big Brother has 36 cameras in the living quarters, four in each room. But these motion controlled Pelco cameras only record when contestants are in the room, so their dailies are manageable. As an all-inclusive average estimate, an editor on a one-hour Reality show can expect 120-450 hours of dailies per episode.

On most one-hour scripted dramas, three editors rotate and cut every third episode. On one-hour Reality shows, eight-to-16 editors rotate and cut every fourth episode––depending on the type of show and quantity of dailies.

On a rigid, 120-hours-per-episode type of series, eight editors and three assistants are likely. On a show like The Apprentice or Survivor, expect 12-18 editors and 9-to-12 assistants and apprentices. Before we delve into further details of editing, let’s discuss shooting.

Masters of Reality

From what I’ve witnessed, many of the producers of Reality television come from news, Entertainment Tonight-type of shows, documentaries or sports. All of these formats involve storytelling without a script; therefore the experience of these producers is advantageous for producing Reality Television.

On a news story, the producer goes out into the field, must oversee the camera people, obtain all the action and coverage that might be needed, and then contemplate a story. The producer also conducts interviews with witnesses and participants. Then he or she comes back to the studio, formulates a story based on the real events but with an angle that appeals to the masses, works with the editor and comes up with a segment for the show. The building blocks of a one-minute news story are very similar to the building blocks of a one-hour Reality show.

Let’s take a look at producing a Reality show with two teams of contestants going about their day, task or challenge. There are no scripts and no directors, so the producers on location (also called field producers), their assistants (called segment producers) and the dozen or so camera people split up and race off with the contestants as they begin to carry out their tasks. The camera people shoot constantly because they never know when something juicy might happen. A talented and creative camera person will vary the frame size and angle and also get close-ups and inserts, which are a godsend in the cutting room. Since there are no scene numbers, everything is shot with time-of-day timecode. And later, that’s how it’s digitized, sorted and referenced.

Nobody knows what incidents may or may not have significance later, so the producers and segment producers take notes on everything, including specific dialogue. If anyone is barking orders to a camera person, it will be the field producer and, without actors performing, it’s not considering directing. The producers and segment producers also interview the contestants several times during each day and ask innumerable detailed questions. The interviews they record are called “sound bites” (or “bites”). Sometimes the bites might total 10-20 hours of that day’s dailies. These bites, when intercut into the show, are vital elements that help to explain and propel the story or mask thin spots in the coverage. They can even be used as a narrative.

So Long Script, Meet Downloads, Pods and Logs

On series where contestants are followed 24/7, normally two teams of producers and segment producers rotate every other episode. Contestants may not sleep, but the producers need to, and more importantly, they need time to organize and type their notes. After an episode completes shooting, a synopsis of what happened is typed up; this is called a “download” or synopsis. The producers and segment producers then brainstorm to come up with the best story points and emotional angles to formulate a story based on the traditional three-act story structure. They then make up a list of “pods.”

A pod is a removable unit, an emotional beat, which hopefully can be combined with others to form a scene and ultimately a complete story. Normally these pods are written on three by five cards, and pinned to a bulletin board in the cutting room. A pod is a shell; moving, omitting and adding pods is like a shell game that doesn’t end until you come up with a good story.

As each day of shooting completes, the daily tapes are sent to “loggers.” It’s easy to spot the loggers; just look for a room filled with a dozen 18-22- year-olds wearing headsets, sitting in front of television screens and typing their brains out. Working day and night shifts logging the 50-150 hours of dailies per day, they just barely keep ahead of the editors. The most common software program used is Pilotware and it allows the loggers to enter brief synopses of the action with timecode ins and outs. Theses logs with clip descriptions and timecodes for each daily tape are used not only by the producers and editors but also by the assistant editors to digitize dailies. Full transcriptions are done for the interviews.

In lieu of a script, the editor is given (and sometimes must ask for) the producer’s notes, the download, a list of suggested pods, the logs and the bite transcripts. Depending on the quantity of dailies, assistants may have started digitizing as early as four weeks before the editors start cutting.

Sometimes the producer orally recites the story as he or she saw it on the set, always promoting tiny moments into grander scenes and hoping the editor can make something out of nothing. Many times the fabulous pod of which the producer spoke is less than stunning––even boring––more of an optimistic memory from his or her imagination. When a good editor with story sense meticulously goes through Reality dailies, the pieces with emotional value, humor or story jump out at him or her. A good producer knows that, which explains why editors in Reality get $500-2,500 above union scale and are treated with a level of respect approaching that of producers.

Every time an editor of Reality starts an episode, it’s like starting an aggressive hunting mission because he or she has to search through a jungle of footage looking for some semblance of a story. It actually can be quite fun and creative.

How Real Is Reality?

Is all Reality real? Well, ultimately yes, because those are real dailies––there’s no CGI going on here. But let’s be honest. If someone followed my neighbor around with two cameras for 72 hours and edited him into a 42-minute episode…he could be made to look like either a bumbling idiot or a complete genius. He could be cut to only when he said stupid things and moronically nodded his head or he could be made to look witty as hell. On a Reality show, these powerful editorial choices are made by the editors in collaboration with the producers with the intent to make the most interesting, comprehensive and compelling story.

How Many Editors Does It Take to Cut a Reality Show?

It’s not realistic for one editor to cut 450 hours of dailies on a TV schedule, so there are teams of editors. For example, there are four teams of three-to-five editors per episode. The specifics vary based on airdates, type of format and amount of dailies. Each editorial team normally has its own team of producer, segment producer and/or story editor. The teams then screen for executive producers, studios and networks like on scripted television.

It’s common to have one editor who cuts all of the elimination ceremonies for every episode. On a team, one editor might cut the openings and closings of each episode while two more editors each cut a different team of contestants doing their tasks or challenges. Conversely, on some shows with fewer dailies, two editors each cut two acts. On a half-hour, room renovation-type of series, one editor can usually keep up with the 17-27 hours of dailies. A lot of those renovations shows have locked down cameras that record day and night but once speeded up, equate to just minutes of cut material.

A string-out might be 50 minutes for a five-minute scene and will include only the bare bones, no cutaways. Nonetheless, five or 10 hours of dailies whittled down to 50 minutes can sometimes be helpful and timesaving to the editor.

Throughout the editing process, each editorial team collaborates and discusses what’s happening in their segments so that the story meshes and doesn’t contain contradictions or duplicate sound bites. Segment producers and/or story editors are available to help find bites and sometimes even to search through dailies. Once the show has gone through a couple of passes with the executive producer, and is perhaps three-to-six minutes over, it goes to a “finishing editor” and the remaining editorial team moves on to start another episode.

Why and what is a finishing editor you ask? Well, if I’m cutting Contestant Team One, it’s a waste of time for me to cut a dazzling day-to-night transition when it’s possible the editor of Team 2 has used the same transition shots. Likewise, why should I search hours for the perfect music cue only to find out that the editor cutting the opening sequence already used it and it works better in his sequence? Therefore, the finishing editor goes through the show and builds the transitions, adds a consistent style, smoothes out cuts for continuity and gets the show to time.

Finding and Working with Your Dailies

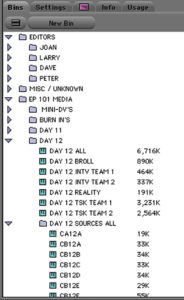

Projects in Reality Television have a lot more folders than scripted shows due to the quantity of dailies. Without folders, the bin scenario would be unmanageable. Dailies will be in a folder titled “Dailies” or “Media” or whatever the assistant editor has been instructed to label it.

There are no scripted scenes, no scene numbers and no slates amongst 450 hours of digitized material. All of the daily tapes shot are recorded with time-of-day timecode. This reference is invaluable and the key to your successful navigation. It is imperative that the camera people be meticulous about synching up throughout the day to assure that the time-of-day code remains accurate.

When a good editor goes through Reality dailies, the pieces with emotional value, jump out at him or her… Which explains why editors in Reality get $500-2,500 above union scale.

There are two exceptions. First, often there are mini-DV camera tapes that have been shot during the day which do not have time-of-day timecode. However, these mini-DV tapes will be notably labeled and/or in their own special bins so you just have to check for them. Secondly, on some shows, motion-controlled Pelco cameras are only digitized if specifically needed and requested.

Let’s say you are asked to cut the Team One Task for episode 101. You would find out what day and at approximately what time it started. Let’s say it was Day 12.

Diagram 1 is quite typical of how dailies on Reality shows are organized. You would first open the “Media” folder and then the “Day 12” folder. The “All” bin includes all of the dailies shot that day. For the task for Team One, note that the applicable dailies have been sorted into two bins: the “Tsk Team 1” bin and the “INTV Team 1” (these are the sound bites) bin. Everything you need to cut the task for Team One will be in these two bins. If the task occurred over two days, you would need to access an additional day as applicable.

The “Day 12 Sources” folder has all the dailies sorted by individual tape numbers. This is handy if you want to confirm that everything shot on a particular tape was indeed digitized. Some editors like to use the “All” bin and sort by timecode; then everything shot that day is listed in chronological order.

The bin labeled “Reality” contains everything but the task. In other words, tape shot in their living quarters, when they first wake up and before they go to bed. And since there are almost always pre-elimination ceremony scenes and post elimination ceremony scenes (where the contestants bemoan whoever was kicked off the show), those dailies will be under “Reality.” If you are assigned to edit a task, you can bet another editor will have been assigned to cut the “Reality.”

The finishing editor goes through the show and builds the transitions, adds a consistent style, smoothes out cuts for continuity and gets the show to time.

Whittling Down Dailies

After reading the logs, transcripts and watching some dailies, a story editor may have cut and pasted the basic scene or story information into what looks like a script, with timecodes for reference. This is the closest one will ever come to getting a script on Reality, and sometimes an assistant editor will have prepared a “string-out” of this script for the editor. A string-out is “chunks” of Reality dailies cut together jump-cut style, including bites, and into an edited sequence.

A string-out might be 50 minutes for a five-minute scene and will include only the bare bones, no cutaways. Nonetheless, five or 10 hours of dailies whittled down to 50 minutes can sometimes be helpful and timesaving to the editor. Conversely, sometimes a string-out is just a bunch of crap put together by an assistant editor based on a paper cut made by a wannabe story editor that was a PA last month. In other words, it’ll never work and never be good and the picture editor is better off to start from scratch.

The task of one team might ultimately be only 10 minutes of airtime in a one-hour episode, yet involves searching through 80 hours of dailies. Many editors cut together their own string-outs, using every key point mentioned in the pods. The problem with this method is that if the pods don’t work or are nonexistent, the editor is back at square one with 80 hours of raw dailies.

In order to avoid going through dailies more than once, many editors pull everything related to the download and pods, plus any humor, cutaways or story that jumps out at them––anything that might come in handy. These are called “selects.” Ideally, if the selects have been pulled meticulously, the editor never has to go back to the raw dailies because virtually anything worthy will be in the “Selects Everything” bin.

On a Reality show, these powerful editorial choices are made by the editors with the intent to make the most interesting, comprehensive and compelling story.

Working with a Team

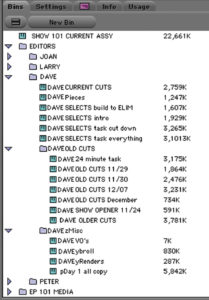

There can be numerous editors working in the same project and if each one had dozens of bins, the cluttered project would be unmanageable. Therefore, the assistant editors create a folder titled “Editors,” as illustrated in Diagram 2. Inside is a folder for each editor who might work on the episode. You are expected to keep all of your bins inside your own folder. Inside that personal folder you may have as many bins and folders as your heart desires.

It’s logical, common and expected that each editor have a “Current Cuts” bin with his or her cut sequences inside. This way when it’s time to screen and everybody’s cuts must be combined, the finishing editor can find the cuts easily. If you don’t want somebody to see it, don’t put it in the current cuts bin. That’s the rule. (Add your name or initials to the bin name to differentiate it from the “Current Cuts” bin of other editors. When titling your cut sequences, include your initials and the date.) Editors are also expected to have an “Old Cuts” bin and a personal “Render” bin; any other bins are entirely up to the individual.

Go Forth

With the above details of editing Reality Television, fellow editors should be well prepared to tackle their first Reality show, sufficiently aware of the tremendous creative opportunities. And if you’re up to it, you can wear the multiple hats of editor and producer and become a preditor.

Due to the controversial nature of Reality Television, the author of this article has chosen to remain anonymous.