By Rob Callahan

This issue’s column is about Andrew P. Jones, a picture editor in Los Angeles in the present day. Before we get to Jones, though, I need first to flash back several thousand years.

Whether in holy texts or in the movies, storytellers often give their villains the most memorable lines of dialogue. So it is in the book of Genesis, in which Cain, hoping to hide his murder of Abel, famously asks, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” The moral here is obvious. A selfishness that disavows all responsibility for others’ welfare is a sin.

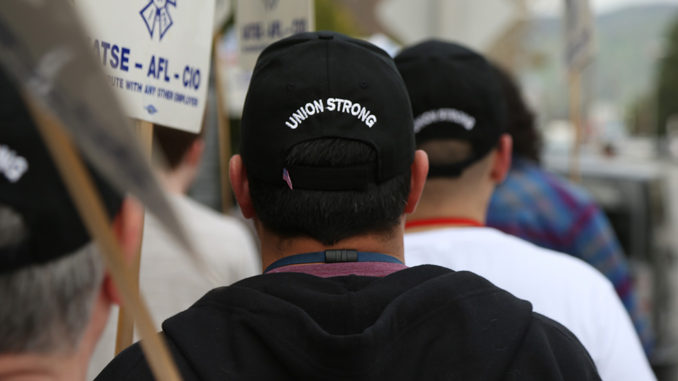

Cain’s question may have been just rhetorical, but we in the labor movement have a clear answer to it: Yes.

Within the family of labor, our enlightened self-interest requires that we assume responsibilities for one another and for our shared interests. This idea of mutual stewardship defines who we are as a union. The IATSE Constitution states that the object of our union is “to achieve, by organization and mutual endeavor, the improvement of the social and economic conditions of employees.” It might as well have simply declared that our purpose, as unionists, is to be our brothers’ and sisters’ keepers.

Every two weeks, the Guild’s Los Angeles office schedules an orientation for prospective new members so they can learn all about our union. Each new bunch of orientees arrives with a lot of pragmatic concerns: How does the roster work? What are my initiation fees? How much are dues? What does the contract say about overtime? How long do I need to work before I get health coverage? Can I work occasional non-union jobs after I join?

It makes sense to ask such questions about the mechanics of union membership. The workings of our organization and of our contracts require a certain amount of bureaucracy, and newcomers will understandably want logistical details about the movements of the machine. But the orientees who arrive full of questions about the mechanics of membership have often given little or no prior thought to the meaning of membership. Amidst all the attention to details, big questions — Who is the Guild? Why is it worth joining? What role do I have to play in it? — go unasked.

To one who disavows all responsibility for his brethren, the advertisement of such disavowal is appropriate comeuppance.

For that reason, I usually address each group orientation and lead the attendees in a discussion of the big-picture questions. My message is simple: the Editors Guild, like any union, is a group that seeks to empower members in the workplace through the exercise of solidarity. At its roots, a union is just an agreement amongst colleagues that they will look out for one another and stand together to defend each other. The union is not the physical office space where the organization has its headquarters, nor is it the Guild’s paid staff, nor even is it our elected leadership. The union is the membership. More precisely, the Guild is simply the vow that members make and keep to each other, the pledge to be our sisters’ and brothers’ keepers.

For several years now, more or less once every other week, I have repeatedly addressed our Angeleno orientations, giving talks about the importance of solidarity. For years I have been explaining that our membership pledge is a solemn pact that members enter into with one another. The orientation of December 19, 2013 was like many such previous orientations, with one key distinction. To my knowledge, that was the first of these bi-weekly sessions to include someone with a history of crossing his colleagues’ picket line.

While his colleagues were on strike in November of last year, Andrew P. Jones, an editor working chiefly in unscripted television, repeatedly crossed an IATSE picket line to service the show Naked and Afraid. In crossing a physical picket line, Jones crossed his co-workers, making it less likely that they would prevail in their dispute with their employer. He crossed, too, the community that coalesced in support of those co-workers and the spirit of solidarity they embodied.

My column in the last issue of CineMontage, “Clothed and Courageous,” told the story of these strikers. I wrote of the heroism and camaraderie they demonstrated in standing together to demand better of their employer. By forging a unified front, they were able to win big improvements in their jobs, including large pay raises for assistant editors and health and retirement benefits for everybody.

Most of us understand what Jones did not: It is not just business. We are a family. We have duties to one another.

It is worth noting that the Naked and Afraid crew’s decision to strike for a union contract was not unanimous. A small minority of crewmembers had little interest in organizing. But only a single editor continued his work without interruption for the duration of his colleagues’ weeklong strike. That editor was Andrew P. Jones. It was this same Andrew P. Jones who unexpectedly showed up at our orientation, a month later, to learn about and apply for membership in the Guild.

I do not pretend to speak for Jones. I cannot say why he did what he did. I am writing neither a screenplay nor scripture, and I feel no need to give him any quotable lines. Those interested in his side of the story can ask him for it themselves. I know only that, for a week in November of 2013, he crossed a picket line in Sherman Oaks to work as a strikebreaker. He then sought to join the community he had so profoundly betrayed.

Why name Jones in this space? Why announce his deeds to the membership? Such publicity might only boost this individual’s career, by advertising to anti-union employers his willingness to undermine his colleagues’ solidarity. What good does it do to broadcast this man’s betrayal of his co-workers?

I turn again to the story of Cain. The God of that tale is all-powerful, and is not at all shy about meting out punishment. Far from being soft on crime, the God of Genesis disciplines through floods, rains of flaming sulphur and individual smitings. But God did not strike down Cain, nor permit anyone else to kill Cain in revenge for the murder of Abel. Instead, God decided that Cain’s punishment would be to live with his crime, and to mark him so that he might live amongst people who recognized him for his act of betrayal.

In crossing a physical picket line, Jones crossed his co-workers, making it less likely that they would prevail in their dispute with their employer.

The Guild is not all-powerful. We have an ethical and legal responsibility, one we take seriously, to represent fairly all those employees for whom we are the designated bargaining agent, regardless of their individual attitudes or actions towards our union. Although the union is legally empowered to fine or expel any member who works as a strikebreaker, we do not have any brimstone at our disposal, not even for the purposes of raining down upon the heads of scabs.

But, just as Cain’s criminality was its own punishment, it seems fitting that one who has betrayed our core principles be known to all those he has betrayed. To one who disavows all responsibility for his brethren, the advertisement of such disavowal is appropriate comeuppance. For this reason, the membership ought to know that this individual had crossed them.

Fortunately, such actions are as aberrant as they are abhorrent. We are better than that. As was demonstrated by the community that closed ranks to form the picket line Andrew P. Jones repeatedly crossed — a community comprised largely of folks who were strangers to one another as individuals, and strangers to the striking crew to whose assistance they rushed — most of us understand what Jones did not: It is not just business. We are a family. We have duties to one another. We are strongest when we are one another’s keepers.