by Betsy A. McLane

There is something of the occult in the job of creating sound for film. It is an art as well as a craft, and when superbly executed, sound design can make a film soar. As author Kevin Donnelly points out in the beginning of this book, occult need not refer to satanic or mystical; it also means unapparent or hidden from view.

With this definition in mind, it is easy to understand how sound in films can be considered occult. Sound is invisible. Movie audiences do not usually think about how the sounds that they hear are achieved. Sometimes audiences know that they have been surprised or frightened by loudness or effects and may notice when music draws attention to itself, but generally the public questions what they are hearing only when the sound is mistakenly out of sync with the image. The many people who create sound, especially those who edit, are likewise invisible to the public — even as their contributions are central to making onscreen worlds. They too are part of the occult magic of cinema.

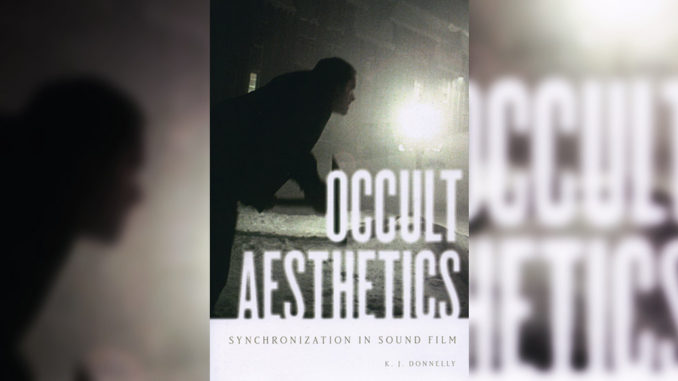

If the above description seems too artsy or abstract, Occult Aesthetics is not for your bookshelf. If you like the idea of exploring the sometimes harmonious, sometimes problematic relationship between sound and image from a non-technical, historical perspective, then this book — with its murderous cover image from Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining — is a provocative addition to your library. Donnelly is an academic based at the University of Southampton in England. He is the author of three other books about sound and film: British Film Music and Film Musicals (2007), Film and Television Music: The Spectre of Sound (2008) and Pop Music in British Cinema: A Chronicle (2008). Knowing this and that the publisher is Oxford University Press, you might expect Occult Aesthetics to be dry and impenetrable. It is quite the opposite.

Donnelly is obsessed with analyzing the way that sound and image play with and off each other. His premise is that when merged onscreen, audio and visuals build a special synergy in human perception, and that this effect is lost when one becomes aware of its existence and how it is made. This fairly simple idea — “Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain” — is here treated with such concentration and detail that it becomes fresh.

Occult Aesthetics is based in theory and, through extensive use of footnotes, offers a good overview of previous discussions of the philosophy of sound and music. Donnelly draws upon writings of silent film genius Sergei Eisenstein as well as Pierre Schaeffer and his protégé Michel Chion, both French avant-garde composers and writers about sound. (Walter Murch provided the introduction to the English translation of Chion’s book Audio Vision: Sound Onscreen, 1994).

Sound is invisible. Movie audiences do not usually think about how the sounds that they hear are achieved.

Like these writers, Donnelly does not rely solely on speculation or imagination to make his points. He states in the preface, “As psychological underpinnings and inspiration, this study uses scientific, functional, neurological and psychophysical ideas about human beings and sound to develop its argument about the perceptual primacy of cinema’s dynamic interplay across synchronized and unsynchronized sections of film.” This sentence is typical of the author’s style, and although it may initially seem dense, Donnelly goes on to explain what he means by noting the learned, Pavlovian expectations of audiences: “For example, the sound of wood blocks clashing together is the accepted conventional sound of someone being punched or kicked in an action film, whereas the actual act of doing this involves no such sound.” In another example, he applies scientific data such as the fact that differences in synchronization of less than 20 milliseconds do not register in the human brain.

The chapter titled “Isomorphic Cadences” is specialized and rather obtuse, unless one is a fan of experimental cinema. More accessible is “Visual Sound Design: The Sonic Continuum.” This looks at technical and aesthetic developments as Donnelly develops his historical approach. He cites an article that explains how, in William Friedken’s The Exorcist (1973), the scary sound from the attic, the source of which is never revealed, was achieved by mixing sounds of guinea pigs running on a sandpapered board, a band saw flying through the air and scratching fingernails. The author then compares this to the original score by Edmund Meissel for Battleship Potemkin (1925) in its use of music combined with noises to point out that noise/music/sound experimentation has been a part of film at least since the 1920s.

Innovative sound in a train station scene in Josef von Sternberg’s Shanghai Express (1932) is illustrated with a series of frame enlargements. These make clear how innovative this film was, at a time when many were struggling to adjust to sound pictures, in its contrast of lateral movement within the frame, close-ups of its stars and the tolling of the station bell. A similar close analysis of the use of the seemingly innocent jingle of an ice cream truck to portend death in John Carpenter’s Assault on Precinct 13 (1976) explains one of the reasons why this film is so haunting.

With examples such as these and many others, Donnelly creates a convincing argument for his theories in Occult Aesthetics.