by Michael Goldman • portraits by Martin Cohen

Although they are still in the frenzy of the final mix in early October, co-music editors Paul Rabjohns and J.J. George somehow find time to usher a visitor onto a Warner Bros. mixing stage to discuss their one-year-plus adventure editing the music track for a new superhero epic, James Wan’s Aquaman. The film, which opens through Warner Bros. December 21, is based on the long-running DC Comics character and features Jason Momoa in the title role as the grizzled, half-human scion of a legendary undersea kingdom known as Atlantis.

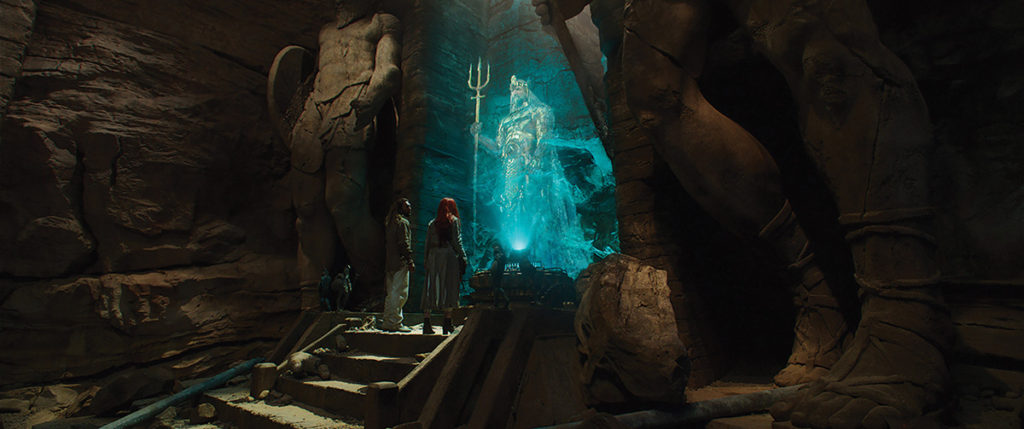

Aquaman grew up on land, but is eventually persuaded to reclaim his birthright as king of Atlantis by preventing nefarious forces from taking over the kingdom and launching an attack on the surface. It’s a character Momoa first debuted in Warner Bros.’ Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016), launching DC’s Justice League series, and is the latest attempt by DC and its owner, Warner Bros., to expand its cinematic superhero universe.

Thus, it’s a “really big movie,” as Rabjohns puts it, and so despite being well into the final mix, he and George are still editing some of the film’s music as final visual effects and director’s tweaks keep trickling in. It’s obvious they have been working extremely diligently at it — Rabjohns for over a year in the film’s editorial offices on the Warner lot, and George for 10 months in the Santa Monica office of composer Rupert Gregson-Williams.

“To be frank, we are both dog-tired,” Rabjohns admits. “Not a lot of sleep last night.” George primarily worked alongside Gregson-Williams, while Rabjohns handled input from the director, producers and studio executives. But eventually, they came together, literally and figuratively, to compile all the threads.

According to George, “There is so much music in the movie that, when I started, there were three other music editors — Paul, along with Jeanette Surga and Peter Oso Snell — already working on the temp. Meanwhile, the composer had things he needed to get going, and there was a certain workflow I helped him develop.”

It would be difficult for somebody to shift gears from working on a full-blown temp on a film this size into tracking underscore cues at the composer’s studio; those tasks are too far apart, George acknowledges. “The way our process unfolded, Paul and I were working toward each other,” he explains. “I was paying attention to what he was doing, because where the temp is going helps us with spotting and musical communication on things like what kind of tone the director is looking for. And then, eventually, new material is written and put into demo form. If the director likes it, we hand it off to Paul to try in the temps. So slowly it starts to cross-pollinate, and once it all began to come together, we ended up here on the scoring stage together.”

For his part, Rabjohns started on the film in September 2017. “But I was here in LA while they were still shooting in Australia,” he clarifies. “They would send me cut scenes, and I would start putting temp score to them and sending them back to Australia. When production came back to LA last November, we really started up on the temp score, continuing the process here.”

In what he calls a “really unusual preview process” for a film, Rabjohns reveals, “Aquaman actually had a preview audience for the very first temp, the end of the director’s cut. Normally, that temp is just for filmmakers and studio executives. But they decided to screen it for an audience — and that meant we had to have the music much further along, because we were showing it to members of the general public. We had to race to make the temp track feel like a finished movie in terms of music.”

And that’s why for the temp track phase the producers added Surga and Oso Snell to the team. “James Wan wanted to do a lot of experimentation and try different styles of music and approaches to scenes during the frenetic director’s cut period,” Rabjohn continues. “So he wanted as much creative horsepower as possible before that first preview screening. Jeanette mostly worked on two particular set-piece sequences in the middle of the film, which involve a big chase, while Peter concentrated more on a big reveal toward the end of the third act.”

Picture editor Kirk Morri also created temp score options for certain key scenes along the way. According to the music editors, the eventual temp track these collaborations produced was crucial for the project’s eventual success because it helped filmmakers figure out the thematic approach they wanted to take throughout.

Rabjohns worked on the temp track for almost a year, through four preview screenings. “Although Rupert’s score doesn’t sound like the temp music in the final film, the temp score was particularly useful for the director to explore a lot of different ideas, and led him to a general philosophy for the way a score might ultimately work in the film,” he elaborates. “Through the temp process, James came up with the idea that modern-day Atlantis exists underwater and is a society much more high-tech than the surface world. To that end, he wanted to distinguish Atlantis musically by making its musical signature very electronic.

“James really liked the use of electronic music in the movie Gallipoli [1981],which used composer Jean-Michel Jarre’s themes for a big action sequence,” the music editor continues. “We experimented with blending some of the big synth composers of the late 1970s with modern electronic scores for the temp. Eventually, Rupert came up with different music, but the idea of using electronics came from the director experimenting with us.”

By contrast, Rabjohns adds, the backstory about the legend of ancient Atlantis is glued together with “very classical music, with orchestra and choir, that works very well. There, you are dealing with ancient times, and that is not a time to use electronics.”

Meanwhile, the main Aquaman theme is “super epic,” according to George, strategically designed, like in many superhero films, to be distinguished from ordinary anthems. “Rupert wrote strong themes for all the main characters in this film, but in a classical way,” he relates. “Some action movies in recent years have drifted more toward electronica and rock ’n’ roll driving everything. I think Rupert pulled the main theme back to a nice classical piece: a big, full orchestra but with electronics underneath, which James really liked. It’s a nice combination.”

Similarly, the musical theme that accompanies the key villain, known as Manta, is very techno-driven, according to Rabjohns. “We worked on that in the temps, but never got a complete theme for Manta until James came up with the idea of making him more industrial,” he explains, delineating the musical themes in Aquaman: “The emotional material in the movie is very orchestral; modern Atlantis is electronic; and Manta is industrial.”

There was also a remix of Depeche Mode’s song “It’s No Good,”done by Charlie Clouser, formerly of Nine Inch Nails, that accompanies a montage of Manta building his equipment. “It’s very industrial-sounding to give a hard-edged, brutal side to the character,” Rabjohns comments.

Warner Bros. Pictures & DC Comics

The primary challenges in editing the film’s music remained evident even as late as the final mix; Wan was constantly experimenting and changing things around, causing the music editors to slog through what George calls “a massive amount of material.” Indeed, his editing partner says the process was almost like searching through myriad boxes of “musical Lego.”

“That volume of material is unusual,” George concedes. “The movie is about two-and-a half-hours long, and we had 15 recording sessions, plus a couple of choir dates recorded in England. We were dealing with orchestrators, copyists, programmers… It all has to come together every session, and be in sync with the picture wherever you are at that particular time. On some cues, we did 25 versions of the demos in order to get to a place where James was happy with it. That was on a reel that had maybe 40 versions of that reel itself, after something like 20 temp versions. It’s a demanding process.”

Part of this challenge was the fact that Aquaman is a big visual and sound effects film; there are over 2,400 visual effects shots in it. As a result, the music team spent most of post-production trying to edit and time its work to match pre-viz, post-viz, and even storyboard elements since final shots did not yet exist. This led to still more changes down the road on top of everything else.

“It’s been quite dynamic,” George understatedly comments. “From the point where we finish scoring to when I’m actually handing over material to Paul on the dub stage, we might go through two or three different versions of a reel. And every single cue has to be cut in many different ways to get it to sync properly with new visual effects. It’s subtle sometimes. Many times, it’s easier to add or lose a foot or two than a frame or two when you are cutting musical beats.”

Where sound effects were concerned, the music editors battled to make sure the film’s music and effects would not interfere with each other. “It really helps to have the score stemmed out in many different ways, because if there are problems on certain frequencies, rather than dropping all the music there, you can just drop certain elements,” Rabjohns explains. “So there can be a cool fight scene and the music can still have more of a presence than it would if it was dropped altogether.

“But, again, it’s all up to the director,” he continues. “For instance, we worked on a big action scene involving a tidal wave that we showed in four preview screenings. In three of them, we had big sound effects and music. But in one of them, we had no music at all. Now in the final, the director preferred a version that is almost all music and few sound effects. That’s because rather than being about the tidal wave, the scene is more about how Aquaman perceives the tidal wave from his emotional perspective. In terms of emotion and plot, it’s more complex and therefore we went with more music than sound effects there.”

While these kinds of issues were particularly tedious for the editors, they also forced them to push their creativity and collaborative methods further than is typical. Indeed, the day before they spoke with CineMontage, a major change was requested, according to Rabjohns.

Warner Bros. Pictures & DC Comics

“Yesterday, we had a big cue about the big reveal, where the melody kicks in at a certain point and it builds to a key moment,” he recalls. “Having seen it play out on the stage here, James decided he wanted the melody to start a lot earlier. So we sat with him and moved the melody to where he wanted it to start. But then he left it to us to figure out the end. J.J. came up with an idea we thought could work. On the stage, it was mixed differently, so it morphed considerably from the original version. The director heard the new version and liked it, but wanted to feature the choirs more in the section; they were already there, but not fully featured. So now, it has a more mythical feel to it.”

In addition to the remix of the Depeche Mode song, the movie features a hybrid version of a new Pitbull song, “Ocean to Ocean,” which was written and performed for the movie, combined with a chorus utilizing Toto’s “Africa” covered by Rhea, a female vocalist. The movie also offers an original new song called “Everything I Need,” written and performed by recording artist Skylar Gray, over the end credits — with chunks of the song also woven into various parts of the score by Gregson-Williams. Rabjohns relates that the point of using the new end-title song this way was to make it represent a particular character. “That way, when you hear the song at the end, it has a lot of resonance because you’ve been hearing oblique references to it throughout the film.”

The process of adding “Everything I Need” into the movie was a massive collaborative effort, according to George. “Skylar wrote the song and played it on a piano, and then Rupert took it and orchestrated it,” he says. “We demo’d it, played it for James Wan and the studio, and then it went through a few incarnations where it was sped up and slowed down until everyone was comfortable. We recorded the orchestra overdub for the song and a few underscore cues into which Rupert had incorporated her melody — they are mostly in small, suggestive bits for a particular character.”

To make it all work, the editors emphasize that they had a powerful technical infrastructure at their disposal. They both used ProTools 12 HD, and relied on several plug-ins they found highly useful. These include the Serato PitchNTime program and the ProTools’ X-Form tool for time compression and pitch-shifting work, respectively. But in particular, they say the Izotope RX7 plug-in known as Music Rebalance was a crucial arrow in their quiver.

“That was a game-changer for mixing songs into movies when you only have a stereo master with the vocal baked in,” Rabjohns says. “It enabled us to bring down vocals that interfered with dialogue without having to drop the whole song down, and to mix stereo songs with a bit more finesse. I used the vocal isolator part of the plug-in for that.”

In particular, Rabjohns recalls using Music Rebalance on Roy Orbison’s “She’s a Mystery to Me” (written by U2’s Bono and the Edge) because the director wanted the end of the song to be presented a cappella. “I had done the best I could with phase reversal to remove the stereo information, and EQ’d the best I could to bring out the vocal, but it was only a so-so result,” he says. “But then I tried RX7, and it had an almost voodoo-like ability to isolate the vocal.”

Both music editors feel their Aquaman experience was an opportunity to push the envelope further than ever before, particularly since this was the first in a planned series ofmovies about the character. Therefore, there was no clear template for them to follow.

Warner Bros. Pictures & DC Comics

“It was quite unique,” Rabjohns explains. “I worked on several Fast and Furious movies, and they were all different to an extent, but there were always certain expectations and set pieces in an established franchise like that in terms of how sound and music work together. For that franchise, it’s been evolving for eight movies now, so it’s kind of like a James Bond film. When you see a Bond film, you know what you will get, what the big theme is and all that.

“With Aquaman, this is completely original,” he adds in conclusion. “This is the first one, and so everything we tried was, at the time, a new idea. That was quite exhilarating.”