by Mel Lambert

Released in 1964, director Robert Stevenson’s original Mary Poppins, starring Julie Andrews, Dick Van Dyke, David Tomlinson and Glynis Johns, set a benchmark in the Walt Disney Studios canon of full-energy musicals, combining live-action performances with intricate cel animation. Fast forward 54 years, and the iconic character is back in director Rob Marshall’s Mary Poppins Returns, this time played by Emily Blunt, with co-stars Meryl Streep, Colin Firth, Emily Mortimer, Dick Van Dyke (again) and Angela Lansbury.

Lensed in England at Shepperton Studios and other locations, the sequel is set in Depression-era, 1930s London several decades after the original, with the magical nanny returning to help the Banks Family children through a difficult time in their lives, following a personal loss. Opening in US cinemas through Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures December 19, the film will be released in both 7.1-channel and Dolby Atmos immersive soundtracks.

Spread between Los Angeles, New York and London, the film’s post-production sound crew consisted of sound designers/supervising sound editors Renée Tondelli and Eugene Gearty, supervising music editor Jennifer Dunnington and executive music producer/music supervisor Mike Higham, and dialogue/music re-recording mixer Mike Prestwood Smith and sound effects re-recording mixer Michael Keller, CAS, working together on Stage A’s large-format Avid S6 M40 Console at Warner Bros. Sound in New York. Other key members of the team included music editor Jim Bruening; dialogue editor Alexa Zimmerman, MPSE; sound effects editors Heather Gross, MPSE and Allan Zaleski; and Foley editors Frank Kern, Kam Chan and Steven Visscher.

Tondelli has worked on all of the director’s films, apart from Chicago (2002). “We all approached this project with such excitement, having loved the original Mary Poppins,” she says. “For the most part, because our crew had worked together on Into the Woods [2014], we had a wonderful shorthand with each other that made for a very special collaboration. The film’s 12 songs all have dramatic and emotional significance within the story, so dialogue and music have to hand off to each other in a seamless way. Rob Marshall never wants the film to signal: ‘Here comes the song!’”

The supervising sound editor says she worked closely with Dunnington, “sometimes syllable-by-syllable, from pre-records, ADR and production, weaving the dialogue in and out of the songs,” adding, “Rhythm and timing are paramount to Rob so that every sound from a single breath to 50 lamplighters dancing is equally considered and carefully threaded into the soundtrack.”

One of the film’s more complex scenes takes place at the Royal Doulton, a fantastical music hall inside a porcelain bowl, with live actors and classically animated animals, according to Tondelli. “We recorded impulse responses of various porcelain bowls, and Jim Bruening — one of our music editors — pitched it to the music,” she says. “We fed the dialogue through this impulse response to create our ‘Ceramic World’ sound. To put voice to the animals, I went to London and worked with voice casting director Phoebe Scholfield.”

The goal was to find actors who could also sing and bring life to the characters “without being cartoony,” continues Tondelli. “It was great fun to have a room of these talented people working out their camel or elephant voices. At the climax of one of the songs, various animals — from soprano flamingos to deep basso elephants — are ‘background singers’ on the stage behind Mary Poppins. Mike Higham, our music supervisor, conducted them to get the perfect pitch. Lyrics are very important to Rob, so Mike Prestwood Smith had to be very careful in weaving the animals in and out of the mix to support but not overwhelm the song. This provided a real Atmos treat as we opened up the music hall to envelop the audience using the surrounds.”

Foley is also an important element in a Rob Marshall film. “In the song ‘Trip a Little Light Fantastic,’ there are 50 lamplighters singing and dancing in an abandoned park in London,” Tondelli relates. “Since it was all shot to playback, the Foley tied in the action and provided a rhythmic beat to the scenes. We had a slate floor built on the Foley Stage [at c5 Sound in New York] and brought in several dancers, including the choreographers. They also performed the many animal feet for us in the song ‘A Cover Is Not the Book,’ from elephants to seals.”

While Tondelli focused on the songs, Zimmerman handled production-dialogue elements. “Because the elements we received from production mixer Simon Hayes were outstanding, there was minimal principal ADR,” the supervising sound editor recalls. “Alexa did an amazing job of cleaning up production tracks whenever necessary. Simon also captured any sounds he could while recording production, such as bicycles on cobblestone streets and vehicles used in the film.”

Marshall and Tondelli also looked for an additional sound designer from New York. “Eugene Gearty, who’s also a musician, was a perfect fit as the newest member of our team,” Tondelli offers. “He was working out of c5 in New York, although he lives in South Carolina, and soon chatted with Rob Marshall on the phone from London.”

“We got on very well,” Gearty says. “Rob and I talked for a long time about needing an uplifting movie in these crazy times, about artistic intent and the role of sound design in his films. He likes his crew to work close to where he edits his films, but was okay with me working out of my own 5.1-channel sound design room in South Carolina, and coming up to New York for regular meetings. I have a Euphonix MC Control and an eight-channel MC Mix for Pro Tools, with Genelec speakers. After the first and only temp mix in early 2018, when I met the two re-recording mixers, I moved up and stayed in Manhattan during the three months of pre-dubs and finals.”

Sound Design to Support the Musical Numbers

As Gearty recalls, “The style we were after — and one that Renée helped to refine with me — was a detail-oriented sound design to support and work with the musical numbers. Unlike an effects-heavy film, our sound design for Mary Poppins Returns concentrated on establishing the world of ’30s London using convincing backgrounds, effects and layered Foley, which we recorded in both Toronto and New York.”

While acknowledging that a great-sounding scene can be created with authentic sound effects, Gearty feels that it is more important that the sound design support and not intrude on the musical numbers. “In fact, everything was designed to work with the cues musically — not just tonally, but also rhythmically,” the sound designer emphasizes. “We had a spotting session against a rough cut. From that point, we used the picture editor’s [Wyatt Smith, ACE] temp track with its effects as a blueprint for the soundtrack. Renée concentrated on dialogue, music and ADR, while I oversaw the sound effects and Foley. It was a highly collaborative effort moving forward. Our philosophy was to serve the script and support what was on the screen.”

A major hurdle for Gearty to clear was accommodating effects against the full-on music tracks. “In other words, how to make your Ferrari Testarossa sound powerful when you have the Blaupunkt radio turned up to 11 listening to Led Zeppelin’s ‘Whole Lotta Love,’” he analogizes. “We understood going into this project that a musical needs effects to sound like it is really happening then and there. Focusing on dialogue, music and visuals, we used well-crafted specific backgrounds, effects and Foley to help the performances of the songs sound as if they were happening right there in London, as opposed to sounding like they were recorded on an ADR stage. It would be a process that took 10 months to evolve.”

After a temp dub, the post crew received positive feedback from the director and Disney Studios, Gearty relates. “‘You hit a home run,’ Rob told us. ‘I don’t want to change anything!’ Of course, we then spent months refining and creating elements after our temp mix!”

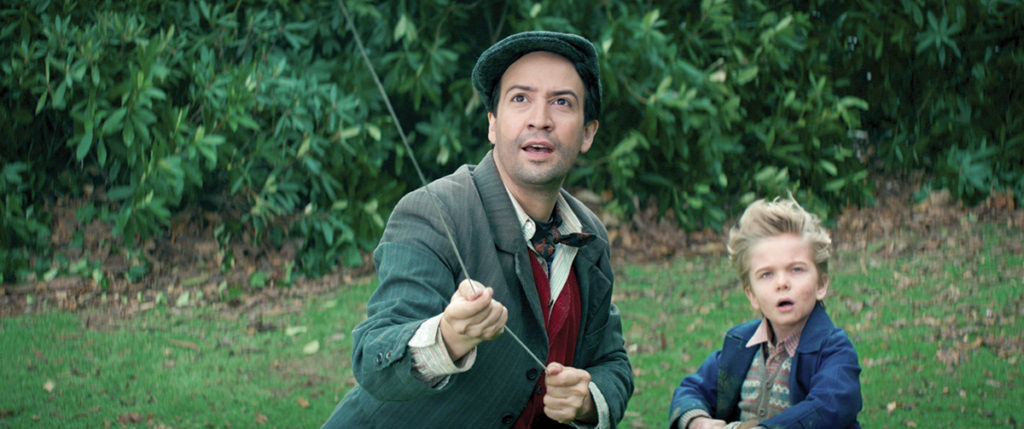

During the Royal Doulton Music Hall scenes, the film moves into “Ceramic World,” but the porcelain tubs and sinks were not working for the footsteps, according to Gearty. “So we had one of our Foley artists, Andy Malcolm, walk on a marble surface, and then sweetened the simple marble footsteps with sweeteners that he made on various ceramic surfaces,” he explains. “I also had my assistant, Sam Mille, make a 5.1-channel and a stereo impulse response of a bowl — a Tiffany Royal Doulton — to add an overall resonance to our Foley/effects tracks. I then made slight changes to each track using variable pitches and other settings to create slightly different sounding footsteps for each character, depending where they were in the cracked bowl, with higher pitched clicks for the kids and lower pitched for Jack [Lin-Manuel Miranda]; of course, Mary Poppins got an extra special treatment. The other Foley elements also received the same impulse response sound.”

Perhaps the biggest sound effects sequence in the film is a chase scene that follows the music hall revue. “It was a nightmare sequence in which Georgie Banks [one of the children] is kidnapped and taken away in a coal-fired steam car — and a wonderful opportunity to create a very scary sound design sequence,” Gearty continues. “Although it had a very strong music cue, I had a lot of fun designing the steam car — thanks to Jay Leno’s Stanley Steamer — and the chase to sound very threatening. Mixer Michael Keller brought my design work to another level; he really made that scene scarier than I had initially designed. So another nod to the team for making the whole bigger than the sum of its parts.”

Live and Pre-Recorded Musical Elements

According to music supervisor Higham, who oversaw all aspects of the film’s music, the orchestral tracks and some cast vocals were pre-recorded with an 82-piece symphony orchestra in January 2017 at Air Lyndhurst Studios in North London. “We had five days to record the orchestra and a very small amount of scratch vocals,” Higham concedes. “Actors were at these sessions so that we could choose tempos with which they were comfortable. A month later, we had seven days of vocal pre-records at British Grove Studios in West London, where the actors sang to the pre-recorded orchestra tracks.” Adds supervising music editor Dunnington, “These tracks were then mixed and used for the playback on set and for the majority of the final film mix.”

The film’s actors were asked to sing out during the shoot rather than mime their songs. “I always feel that it looks much better if actors sing out when they’re acting,” the music supervisor says. “This became invaluable because we ended up using some of the live vocals from several of our actors. We also recorded additional vocals after the fact, as there were sections of performance that we wanted to change for artistic choices.”

Higham recalls that the most challenging part of his job on the film, which occurred during preparation of the immersive musical soundtrack, was paying attention to detail and ensuring that everyone gave his or her best performance in the studio while the pre-records were done. “Our director was good at reminding the cast where they were going to be, and to try and think ahead, so that they could put their performance into that world,” he explains.

“A key thought was also making sure that our orchestra was the correct size and that we recorded it with a sense of the 1960s, as a throwback to the time of the original film; this was achieved by microphone choice and the players I selected for the orchestra,” he continues. “On set, I would make sure everybody was absolutely ready to sing on the day, and that they all felt comfortable with the loudspeaker setup and in-ear monitoring, if they were using them. We prepared clicks to cue our actors to make sure the lip sync looked as good as it could be; without that you do not have a film at all.”

Dunnington’s most difficult task, she recalls, was “overseeing the large track count throughout the long editorial process, and stitching together the inserts, revisions and overdubs recorded at the three major orchestral sessions,” the last of which took place in May 2018. “Music editorial was extremely involved with the team of orchestrators and copyists to ensure that the material for each block of new recording sessions would consistently match the material from 11 or 17 months prior,” she adds.

Because the main orchestral tracks from the pre-record were not done to a click (so that the songs felt more natural), “We had to create fluid click tracks based on that material, which the orchestra had to follow in order to seamlessly punch in and out of the cues, Dunnington continues. “With several orchestrators on board, there was also a challenge for sonic continuity that had to be carefully monitored to ensure consistency.”

In terms of deliverables, from the studio and on-set multi-track recordings the team prepared 5.1-channel A and B stems of drums, toys, percussion, keys, accordion/cimbalom, synth, jazz bass, guitar, orchestral room, strings-close, harp, woodwind-close, horns-close, brass-close, saxes-close and tympani — plus spare 1 through 3. “We also had three stereo and three mono tracks for some on-camera source music, together with vocal stems,” explains Dunnington. “There were 13 mono tracks — one for each singing character — plus six 5.1-channel ensemble tracks and eight mono production tracks for the live vocals. We also had two sets of the orchestral tracks because, in many cases, the overlapping crosses between cues and songs, or new and old material, was much less complicated to combine if they were checker-boarded for the dialogue/music re-recording mixer.”

Collaborative Wrangling on the Mix Stage

“Because of the film’s music focus, we opted for a 7.1-channel surround format for the target audience, and then spent two weeks opening up that mix with Atmos objects for the surrounds and overheads,” Prestwood Smith relates. “Rob is a Broadway guy who believed that this film should be about live musical performances; it was my role to bring that excitement to the screen, but fully integrated within the rest of the film. After all, music is at the center of the film’s narrative and emotional drive.”

The 5.1-channel stems from music editorial were opened up to 7.1 format using panning and ambience plug-ins. Prestwood Smith received two sets of score stems, each of which was 14 stems wide. “So that we could control everything we needed — especially the solo instruments — the final score contained spot mics on all groups,” he explains. “Vocals were a combination of live and pre-recorded across 48 tracks, including ensemble and group vocals. I also had 30 dialogue tracks with production and ADR. Group was huge, especially in the Royal Doulton Music Hall, with some 60 or so tracks.”

The dialogue/music re-recording mixer had to carefully weave the live and pre-recorded vocals between the dialogue tracks, using processing. “We also had a lot of animated characters and crowd noise during ‘Ceramic World,’” he continues. “That made for a very complex mix, with continually changing balance between dialogue, music and sound design being handled by my co-mixer, Michael Keller.” Following the temp mix, pre-dubs started in March 2018 with finals in June and July.

Working closely with Tondelli and Gearty, sound effects re-recording mixer Keller developed a Pro Tools template based on a 9.1-channel Atmos format with a 7.1-channel output. “The 5.1-channel pre-dubs I received from Eugene were very useful for the temp mix, and formed the basis for my pre-dub mixes,” Keller says. “It’s important on virtual mixes that editors and re-recording mixers agree early on about a mix template. Ideally, editors cut in it so that when we get to the temp stage the Pro Tools sessions are ready to go, and we don’t have to spend hours merging editorial sessions with mixing templates.

The team spent about 15 days on the pre-dubs, with sound effects, Foley and backgrounds. “During the subtle scenes, I spent more time on the backgrounds and Foley to emphasize that characteristic ’30s London environment,” Keller explains. “A key, as Eugene has mentioned, was the Foley, which glued together the vocals and the environments, including footsteps, props, cloth and other elements. The dance numbers took longer to mix because we needed to have the Foley cues play through the big music numbers as more of a percussive component. We wanted everything to sound organic. After all, this film is a musical, not an effects action film.”

While the majority of stage time was spent on the 7.1-channel mix, the team also flagged elements that could be used in the later Atmos immersive mix, “particularly for quieter scenes, since object sounds are harder to locate in loud scenes,” Keller stresses. “The full-range surround and overhead speakers [specified for an Atmos mix] helped the music spread out into the room, especially with the bass extension. But we had to be careful not to change the music balances too much between 7.1 and Atmos.”

To streamline his workflow on Stage A at Warner Bros. Sound, Keller specified two Avid HDX3 systems. “One was the FX/Foley Playback machine, while the other had backgrounds running,” he recalls. “The latter consisted of 10 pre-dubs, with room tone and atmospheres, birds, traffic wash, specific traffic sounds, crickets, etc. Mike Prestwood Smith handled walla and loop group from Renée’s dialogue tracks, together with animal vocals and reactions; that was a busy reel! Foley was primary feet, background feet, props and cloth movements. In terms of plug-ins, I used nothing crazy. I believe that if you need too many plug-ins on the mix stage to make something sound right, you probably haven’t got the right sound effects. Dubbing schedules get shorter every year and there is not a lot of time to experiment with new plug-ins. Having said that, I used Avid Channel Strip for EQ and dynamics, and Audio Ease Altiverb and Avid ReVibe for reverbs.”

Summarizing his experience on Mary Poppins Returns, Keller says that the director “hand-picked a crew that had respect for one another; everyone’s opinion was valued and it was a real team effort. The goal was to create an exciting mix. Rob Marshall was our captain — we did our very best for him.”

“Dialogue and music gave the film its overall shape, and then we layered in the sound design and effects,” adds Prestwood Smith. “Our second pass through a reel was a bargaining process between Michael and me; getting the vocals to sound right meant getting the Foley and backgrounds absolutely right. Refining those details took time, but we always needed to maintain a broad appreciation of the whole film.”

“My biggest challenge was getting the hugely complex ‘Ceramic World’ to sound right with all of its myriad components,” Tondelli concludes. “But it was also my biggest pleasure within a wonderful soundtrack experience. And, most importantly, it’s great to work on a film you love with people you love.”