By Jennifer Walden

Ah, the ubiquitous EQ. It’s an essential audio tool that’s been around since the dawn of sound recording, performing the all-important task of boosting and attenuating specified bands of frequencies.

Today’s EQ, or “equalization,” options — whether they’re outboard, plug-in, or built into the console — are unequivocally more sophisticated than their predecessors, as the tech continues to improve and companies regularly release new versions. But, wow, there really are tons of EQs out there. No matter the DAW, there’s at least one EQ that comes with it. In fact, you get two with Avid’s free Pro Tools|First.

Why are there so many different EQs? Are they really so different? Does one EQ work better for a given task than another? What would make an EQ not right for a job?

I’ve posed these questions to five sound pros with different areas of expertise, hoping to get a better sense of how to choose the right EQ for what you do.

Michael Babcock is a man of many sound talents. He was a sound designer on “Thor” (2011), supervising sound editor/sound designer/re-recording mixer on “This is the End” and “The Interview,” effects re-recording mixer on “Doctor Sleep,” and dialogue/music re-recording mixer on the new “See” series for Apple TV+. (He was also featured in October 2019 in CineMontage’s What Our Members Do).

For Babcock, “EQs are like fine wines. Wait, that’s probably reverbs,” he joked. “EQs are like bottled water — the differences seem very slight but once you’re paying attention it’s easily one of the most important choices you can make as a mixer.”

Sometimes a colorless, transparent EQ is needed — one that won’t impart harmonics, saturation, phasing, or other artifacts. But other times, adding color can help add to or enhance tonal character. “For music, it’s fun to play with the ‘modeled’ plugs of old, those from Neve, API, and the like. For years, I used McDSP’s Channel G because of the great headroom and slight color it has. I still use it on Master stem faders and during sound design creation,” Babcock said.

Dialogue/music re-recording mixer Tom Ozanich — who earned an Oscar nom for his mix on “A Star is Born” last year and is in the Oscar race for mixing this year’s “Joker” — also explores color when mixing music. In fact, when mixing the music on “Joker,” Ozanich went with Plug-in Alliance’s SPL Passeq plug-in “almost entirely for the way the EQ sounds,” said Ozanich. “It’s a passive EQ, so it sounds really good but it doesn’t give you a graphic display. There isn’t an analyzer with an EQ curve and all that; it’s just knobs. It has a high, low, and mid EQs on one side that can only cut and then three EQs on the other side that can only boost. You work them against each other to get the sound you want.”

Whether an EQ adds color or not, it’s important that it doesn’t add unpleasant artifacts or perceptible phasing. Babcock noted, “Inferior EQs tend to break up at certain frequencies, most commonly at the low end. You can hear the quantization error on some EQs.”

Ozanich added, “Some EQs can get harsh or end up sounding fake or take on a grungy character that you don’t want. That would be bad, and I steer away from EQs that do that.”

Another aspect to consider when choosing an EQ is how flexible the filtering is — how wide you can make the bands, how tight you can make the notches, and how much you can adjust the parameters of the low and high-pass filters. Both Ozanich and Babcock like FabFilter’s Pro-Q 3 for several reasons; its flexibility is certainly one.

“For ‘Joker’ and ‘A Star is Born’ — I’ve used FabFilter Pro-Q 3 a ton on dialogue specifically. It definitely gives you scalpel-level precision. You can dial-in ultra-narrow notch filters to remove hum or buzz, but then you can also do more gentle boosts or cuts. You can bend it to do whatever you need it to do,” said Ozanich.

“The Pro-Q 3 gives you up to 24 bands to do with as you please. I particularly like using it on dialogue because you can have filters, bands, and notches all-in-one,” Babcock added. “The amount of choices you have for low and high-pass filtering in Pro-Q 3 is second to none. On a recent mix, a spirited producer hated a certain music cue and wanted it to be something else. I ended up changing the whole intent of the cue by taking certain stems and playing around with the HPF set at -96db, opening and closing the filter like you would on an EDM tune.”

Flexibility in terms of workflow integration is also key. Many mixers are working in the box using Pro Tools sessions mapped to a control surface, like the Avid S6. Plug-ins that map intelligently to the control surface are preferable. “If I have to use a mouse to dial-in the EQ then I’m not happy. I don’t want to spend the majority of my time on a mouse. I want to spend it on the console,” said Ozanich, who is not alone in that sentiment amongst mixers. Ozanich even worked with the Avid team to help improve the way several different plug-ins were mapped to the S6, including the Pro-Q 2 (before the Pro-Q 3 was available).

On a traditional console, the re-re-cording mixer is locked into using the built-in EQs. But that’s not such a bad thing, according to Oscar-nominated re-recording mixer Beau Borders, who is currently finishing the final mix on director Peter Berg’s upcoming “Wonderland” film, and the final mix on “Greyhound,” co-written/co-produced and starring Tom Hanks. “I really love the way the EQs sound on the AMS Neve DFC, the Harrison MPC, and the Euphonix consoles. Also, I’m very used to their functionality and very familiar with how far I can push them. The DFC will always have a fluid sound that’s hard to beat,” Borders said.

And the built-in EQs on a traditional console let the mixer keep his/her hands on the board. “The Harrison MPC especially has a phenomenal heads-up display that gives you visual feedback that’s above and beyond the other consoles,” added Borders.

Going back to the monitor and mouse to fine-tune the EQ parameters is a pain, but the Pro-Q 3 interface makes it worthwhile. “You can’t beat the great graphic EQ display of the Pro-Q 3. You can see and track down specific frequencies in a fast but nuanced manner,” explained Babcock.

Borders is also a fan of the Pro-Q 3 interface. “The spectrum analyzer helps me carve through sounds very quickly, which is essential when you’re working in a room full of impatient clients,” he said.

The Pro-Q 3 offers some innovative features that are a step ahead of other EQs. For instance, there’s the Dynamic EQ feature, which adapts the amount of EQ applied to a band depending on the level of the input signal. And there’s the EQ Match feature, one of Babcock’s favorites. “About three times a year, I fish Pro-Q 3’s EQ Match out of the trick bag as a last resort. It has helped me keep my job as a mixer when some weird off-axis dialogue angle had to match another weird off-axis angle that seemed against the laws of matching sonic physics,” Babcock said.

Borders added, “The EQ Match feature is impressive, and it’s a great first-step to getting dialogue to match.”

Whether mixing music, dialogue, or effects, these mixers have named Pro-Q 3 as a go-to EQ. “The bottom line is I love the way it sounds, and it’s the first plug-in EQ that I’ve used that makes me NOT miss a traditional film console so much,” Borders said.

But what about on the editorial side? What are sound designers and dialogue editors looking for in an EQ? Supervising sound editor/sound designer/sound effects recordist Mac Smith, who’s worked on films like “The Birth of a Nation,” “The Secret Life of Pets,” “Avengers: Endgame,” and “Dawn of the Planet of the Apes,” looks for an EQ that is easy to intuit. “You don’t want an EQ with a steep learning curve. You want to find something that is straightforward and that can help you get a job done quickly,” he said.

Smith likes being able to see what he’s hearing, to identify and reduce/remove any problems very quickly. Smith also prefers Pro-Q 3. He said, “I love the graphical interface on Pro-Q 3. I love the pre/post analyzer option so you can see what you are doing to the sound and what frequencies you are boosting or attenuating. I can grab anywhere on the line and pull out those problem frequencies very quickly, or boost up the frequencies that I want to hear more. That’s why I go for the Pro-Q 3.”

Another major factor for Smith, especially when preparing sessions for the dub stage, is choosing an EQ that the re-recording mixers will want to use in the mix. “I don’t want to put in an EQ across every track in a giant session if it is something that isn’t their favorite. So I almost always defer to the mixer. Some of them like the Pro-Q 3 and other mixers like to keep it super-simple and use something like Avid Channel Strip, which is cool too,” said Smith.

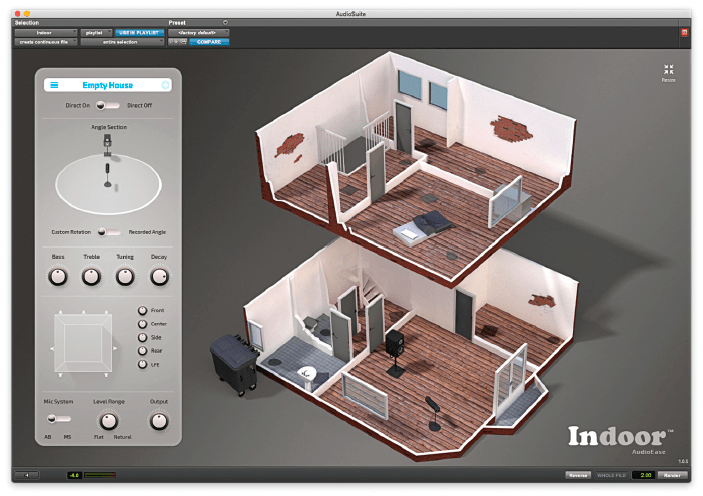

Although it’s not necessarily an EQ, Smith finds Audio Ease’s Indoor reverb plug-in to be very helpful when trying to get disparate sound sources (effects pulled from libraries or recorded by different people at different times in different environments) to all feel like they’re happening in the same space. “I put them through Indoor, and even if I’m only adding a very subtle reverb it makes them all feel like they belong together because in addition to reverb it’s also doing quite a bit of EQ,” he says. “Sometimes processing the sounds like that very lightly — in a very simple space with the virtual microphone and speaker very close together — is a quick and easy way to make them gel.”

Smith used that technique often while designing sounds for “Haunt.” “I was creating different sounds for the coffins opening and closing using different door sounds and different wood creaks. It totally worked. Still, I do keep all of the original sounds muted in the track below just in case the mixer thinks I went too far. But if I can get it close and we’re under a tight deadline, nine out of 10 times it just goes right into the mix.”

In terms of dialogue editing, you’d think EQ would be an essential tool for that job. But Emmy-winning dialogue editor Paul Bercovitch — who cut the complicated and often challenging dialogue on “Game of Thrones” — says he doesn’t “really use EQ in the traditional sense. I find that work is better handled by the mixers on the dub stage.”

Bercovitch does make extensive use of iZotope’s RX7 though, which like Audio Ease’s Indoor is not an EQ per se, but it does modify frequencies within a sound’s spectrum.

“As a dialogue editor, I am approaching EQ much more from a ‘repair’ standpoint, mostly notching out hums and whines. I prefer RX to the notch filters I used to use because often the ‘problem’ frequencies are not constant. RX allows you to easily see the problem and correct it,” he said.

“For my purposes, a good EQ removes ‘problem’ frequencies without sacrificing the integrity of the dialogue. I am not here to make the dialogue sound beautiful. My job is to make it as easy as possible for the mixer to achieve that goal,” Bercovitch concluded. ■

Jennifer Walden is a freelance writer.