By Betsy McLane

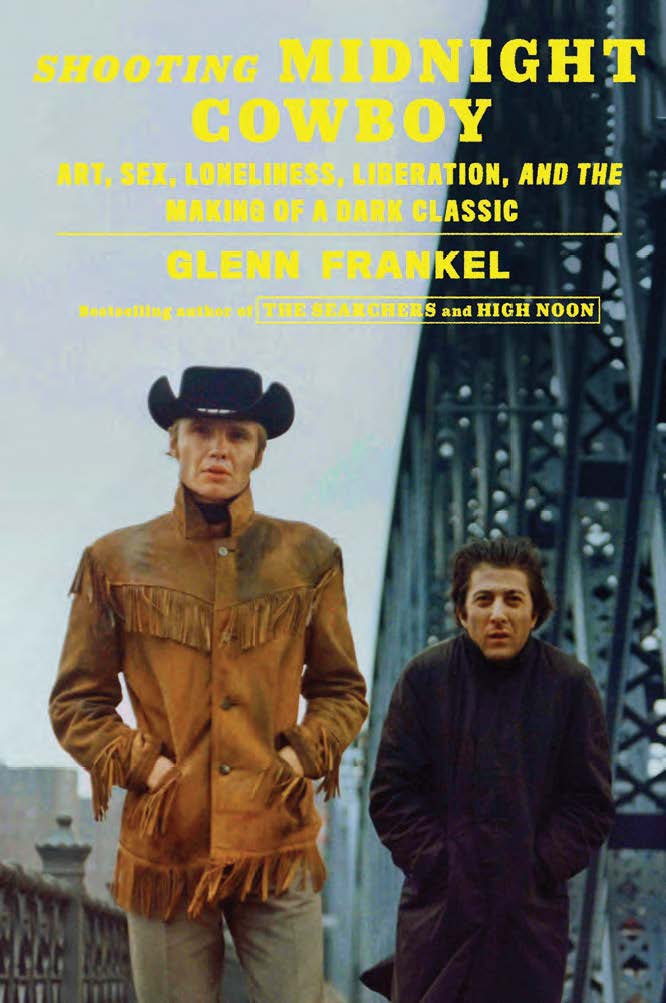

“Shooting Midnight Cowboy” is the wrong title for Glenn Frankel’s absorbing new book, but the subtitle–“Art, Sex, Loneliness, Liberation, and the Making of a Dark Classic”—is perfect. Of course, using “shooting” in a title that also includes the word “cowboy” must have been irresistible. This book is not, however, about shooting the film about the odd friendship between a con man and a male hustler; it is about the people who conceived, executed, and marketed “Midnight Cowboy,” and in the process were part of the sea change that rocked America and Hollywood in the late 1960s.

The first third of the book focuses on the author of the novel “Midnight Cowboy,” James Leo Herlihy. Frankel presents Herlihy as a gifted but tortured artist; the film’s director John Schlesinger is also seen as extremely talented, but self-doubting. Herlihy, the classic Midwestern American boy who goes to New York City to follow his dream of becoming a writer, was haunted by his homosexuality; Schlesinger, the product of cultured parents and British boys boarding school, is more comfortable with his, but both lived amid mid-20th century homophobia. While homosexuality, and social responses to it, are not the main subjects of the story, their force is felt throughout. With this and other topics, Frankel invites readers to connect not only the way films reflect culture, but also the ways in which they change it.

Frankel is a highly respected Pulitzer Prize-winning author of two previous books that dissect single films, “The Searchers: The Making of an American Legend” (2014) and “High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic” (2017). Like those, “Shooting Midnight Cowboy” is meticulously researched, quotations are footnoted and sources fully described. Without any strain of overly academized writing, Frankel offers a nuanced and entertaining work of scholarship. The use of explanatory “making of” phrases in his titles is obviously a successful strategy, attracting readers who might not otherwise pick up the books. Both film professionals and general readers will find an abundance of little-known details and personal stories in “Shooting Midnight Cowboy” that complement Frankel’s insights into the art and craft of filmmaking.

Frankel is a highly respected Pulitzer Prize-winning author of two previous books that dissect single films, “The Searchers: The Making of an American Legend” (2014) and “High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic” (2017). Like those, “Shooting Midnight Cowboy” is meticulously researched, quotations are footnoted and sources fully described. Without any strain of overly academized writing, Frankel offers a nuanced and entertaining work of scholarship. The use of explanatory “making of” phrases in his titles is obviously a successful strategy, attracting readers who might not otherwise pick up the books. Both film professionals and general readers will find an abundance of little-known details and personal stories in “Shooting Midnight Cowboy” that complement Frankel’s insights into the art and craft of filmmaking.

The most savage indictment of New York City ever captured on film.

One of the great merits of Frankel’s work is the weaving of describing the arduous process of creating a film into the artistic, social, and political milieu of its day. In “Shooting Midnight Cowboy,” that culture is the decaying yet defiant New York City of the late 1960s, shot through with swinging London and a rapidly changing Hollywood studio system. The book quotes film critic Rex Reed, who found “Midnight Cowboy” to be “[p]robably the most savage indictment against the City of New York ever captured on film.” The cast of minor characters appearing in the book includes New York Mayor John Lindsay, Bob Dylan, Julie Christie, Mike Nichols, Robert Duval, Truman Capote, Schlesinger’s lover Michael Childers, and Andy Warhol who, with his entourage, epitomize popular culture. Their profiles, along with descriptions of a crumbling metropolis, offer readers a memorable introduction to the city in an era roiling with both fear and possibility.

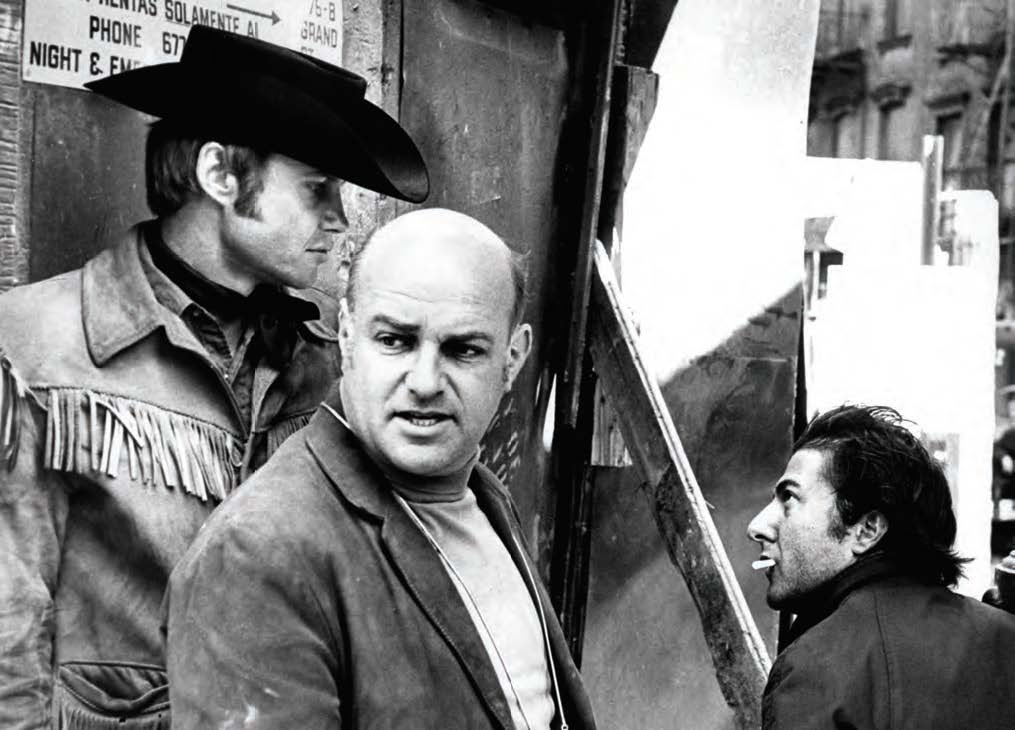

Discussion of making the film begins only in chapter 8, “The Producer,” when Jerome Hellman is introduced as “the most insecure person in every room he entered.” In this respect, he has plenty of competition. Schlesinger, whose lack of self-esteem is seen as overwhelming his personality and sometimes his professionalism, receives the most attention. Frankel also extensively explores the psyches of the film’s two stars, Dustin Hoffman (Ratso) and John Voight (Joe Buck, the title character). Hoffman is caught bedazzled by the overnight stardom bestowed on him by “The Graduate,” admitting to a reporter that “never in my life have I been so in love with myself.” Voight, coming to the project with few screen credits, is confident in his ability to play a role he knew was perfect for him. Screenwriter Waldo Salt’s history with the Hollywood blacklist and familial demons is dissected in detail, and his vital roles in both writing the script and making on-set contributions to “Midnight Cowboy” are appropriately recognized. The same is true of casting director Marion Dougherty and the costume designer Ann Roth. The two women emerge as forceful, grounded individuals who know that they are masters of their crafts. Dougherty championed Voight even when Schlesinger had already hired another actor, while Roth especially stands firm in the ways her wardrobe choices complete an actor’s work, sewing Joe Buck’s iconic leather jacket herself. When her demand for a single card credit was refused by Hellman, he was shocked when she stood by her principles and had her name removed from the film.

Schlesinger, directing his first picture in the US, was used to working with a known group of actors and technicians. The freewheeling intensity of an American cast, and especially the parameters of working with a New York union crew, were difficult for him. The cinematographer was also new to the US. Adam Holender, who at the age of three was sent with his family to a Siberian prison camp, was recommended by his friend Roman Polanski. Although Schlesinger was wary of Holender’s complete lack of experience in American features, the two bonded with the shared goal of presenting the city in new ways. Holender insisted on shooting with a small reflex camera, not the standard bulky Mitchell BNC, and he chose soft light, shooting most street scenes (some of which were stolen shots) with natural light, not with studio kliegs. None of this set well with the crew. Frankel quotes Holender saying, “It was a constant battle. I was in charge, but the crew didn’t like to be told to use something they thought was for still photographers or amateurs. But they were basically decent people and they did what I asked.”

Editing proved to be a much uglier battle. The film’s editor was Hugh A. Robertson, a tall imposing Black man recommended by Arthur Penn. In an interview with Frankel, Irene Bowers, who worked as an apprentice editor, remembered him as, “A wonderful, talented editor, a charming man, but he also had a kind of self-sabotaging streak. It wasn’t an aggressive attitude, but more like ‘You’re not going to make me do anything I don’t want to do.” Jerome Hellman’s recollection was that “Robertson was a disaster.” Whatever the case, Schlesinger and Robertson did not see eye-to-eye, and Schlesinger brought in his English editor, Jim Clark. Clark was known as the “Dream Repairman” for his ability to fix things that didn’t work. He was not in the New York union; he did not even have a green card, but Schlesinger and Hellman hired him as a “creative consultant” while keeping on Robertson and his crew. Clark was able to mollify and reassure Schlesinger. With two of Robertson’s assistants who he observed “were high from morning to night and nobody cared,” Clark worked in one room while Robertson and Schlesinger worked in another.

While Clark was able to calm the volatile director, Schlesinger and Robertson never clicked. As Clark recalled it, Schlesinger would storm into his editing room demanding, “You’ve got to get that scene away from that fucking Black Panther!” Robertson in turn would comment when an emotional Schlesinger left the building, “Momma sure had the rag on today.” “Midnight Cowboy” was hailed as an instant classic.

Among the film’s many awards, Robertson was nominated for a Best Editing Oscar, and until 2016 (when Joi McMillon was nominated for “Moonlight”) was the only African-American to be so honored. His only other feature editing credit in the US was Shaft (1971). Clark, although he had no editing credit on “Midnight Cowboy,” went on to edit many Hollywood features, was Oscar nominated for “The Mission” in 1986 and won for “The Killing Fields” in 1984.

Shooting Midnight Cowboy: Art, Loneliness, Liberation, and the Making of a Dark Classic

By Glenn Frankel

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021 Hardcover, 415 pages, $30.00