By Peter Tonguette

The new Netflix drama-comedy “Beef” starts at a low point in its protagonists’ lives.

On an otherwise unremarkable day in Southern California, prosperous entrepreneur Amy (Ali Wong) and luckless contractor Danny (Steven Yeun) first meet while each is behind the wheel of their cars. There is a verbal altercation; a frenetic chase follows. Much steam is let off. Pedestrians are happily spared in the encounter. For Amy and Danny, however, the incident is too strange, too disturbing, too exciting to move on from. This road rage encounter fuels the rest of the series, which also examines the state of discontentment that led the characters to their so-called “beef” with each other. The show also stars Joseph Lee as Amy’s husband, George; and Young Mazino as Danny’s brother, Paul.

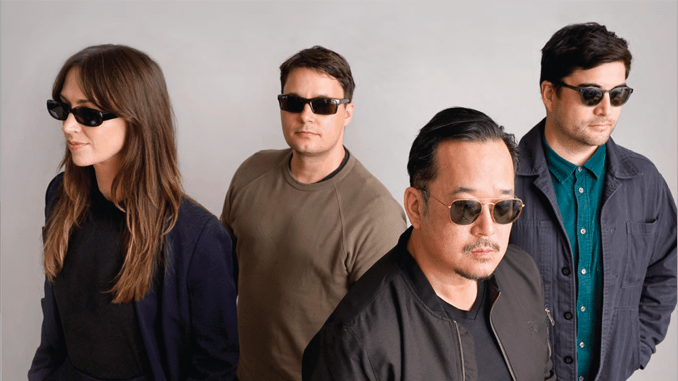

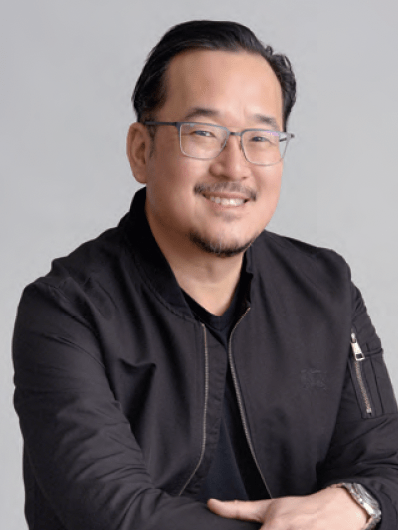

Although the series depicts the consequences and causes of that lousy day, for the four editors who brought “Beef” to life — Nat Fuller, Jordan Kim, Harry Yoon, ACE, and Laura Zempel — the show was nothing but rewarding. Created by Lee Sung Jin, a native of South Korea, “Beef” is one of the few shows in memory to dive deeply into the lives of Korean American characters, an aspect of the show that has a personal resonance for Kim and Yoon, both Asian Americans.

Splitting editorial duties over 10 episodes, the editors collaborated on a show unique in its sociological acuity and memorable for its mixture of dark comedy and drama.

CineMontage recently caught up with Fuller, Kim, Yoon, and Zempel to talk about one of the spring’s most talked-about shows.

CineMontage: Harry, you edited the pilot. How did you get involved with “Beef”?

Harry Yoon: Sonny [Lee Sung Jin] got in touch with me. I think he was looking expressly for some editors to be from a Korean American or an Asian American background. There are so many specific details and nuances that would resonate with the community that he wanted to be in dialogue, ideally, with somebody who understood and could translate some of those references.

Reading the pilot script of “Beef,” I started to recognize that this was a portrait of Korean Americans and Asian Americans in general that we hadn’t seen before. It felt idiosyncratic and grounded and not necessarily dealing with the normal narratives that you see surrounding Asian Americans. These characters were complex in all the best ways, and not just admirable, but also really terrible in specific ways. I loved how balanced and human it felt. Originally, Sonny wanted me to work as a supervising editor, but unfortunately, the schedule got pushed enough where I had to leave earlier than I would’ve liked to start on a feature.

Laura Zempel: I was most excited when I heard that Harry was going to be working on it. He and I worked together on season 1 of “Euphoria,” and he’s been a mentor to me. I really looked up to him, and I really trust his taste. . . . Harry did the pilot, and then he had to leave. I sort of inherited the pilot [as additional editor]. It was great because Harry and I had a lot of trust already built in since we worked together before.

CineMontage: What were the main challenges of cutting the pilot?

Yoon: The original design of the script had a very bold premise from Sonny: we would start with Danny, we would leave him for quite a while, and then lay out the majority of Amy’s life. Then Danny would surprise us at the doorway later on with Amy. That was something that was very bold, very challenging, particularly for a two-handed show with two very dynamic and charismatic characters.

It worked to a certain extent, but I think what we recognized was we were missing some of the delicious parallels that Sonny had laid out in these beats between the characters. In that juxtaposition of those parallels, I think [there is] a clearer evocation of this thesis: that the thing bothering Danny, even though it circumstantially might be different than the thing that is bothering Amy, [suggests] a kind of cosmic parity between those two. What we ended up playing with, with the encouragement of A24 and with Netflix, was more crosscutting . . . . “This is where I have to really tip my hat to Laura Zempel, who created all these beautiful little grace notes in those cuts between the characters.

CineMontage: How did you approach the actual road rage chase?

Yoon: There are definitely several chapters to that. It’s really important to understand where Danny’s head is when he sees that the bird flipped by Amy’s character . . . to show in that little vignette that he is a man that is put upon by the world and that he’s disrespected and for all of us to identify that. That’s something that we could all resonate with.

Then, what we wanted to do from there was to keep escalating the reasons why Danny won’t stop. That the fact that Amy’s car swerves into him as he’s trying to follow her leads him to go into that super-dangerous situation with the red light. Then she escalates it again by starting to throw things at his windshield. Each moment where you think, “OK, this is getting ridiculous,” she keeps escalating the insults. So you start to understand beat by beat why he can’t let this chase go.

CineMontage: What is it about these two characters that leads them to the road rage incident?

Yoon: From the beginning, all of the department heads that Sonny brought on had this ongoing conversation about the void: this kind of hole in our hearts or in our souls that makes us feel like what we have or what we’re doing or what we’ve accomplished isn’t quite enough. Some of us find a way to fill that hole through religion, some of us fill that hole through achievement, but what we see carefully laid out, piece by piece, is how deeply unsatisfied each of the characters are for some reason. It’s like an itch that they can’t scratch. There’s something about this sense of purpose that each of them gets in fighting this other person that allows them to at least look away from that hole for a little while.

Nat Fuller: There’s the element of them breaking out of their mundane life with this experience of having a beef with somebody and having that rivalry. It almost wakes up something in both of them that they needed in a way, but also at the same time it’s very destructive.

Yoon: I think that pivotal moment in Danny’s story in the first episode is when he says, “This isn’t it. I can’t just kill myself. I need to find some other reason to live.” That’s when he discovers the receipt and is reminded that, “Oh yeah, there’s that terrible person that insulted me. If I can only get revenge on that person, maybe my life will have meaning.”

CineMontage: Since the show is all about the aftermath of the initial incident, how did you assure that the episodes flowed from one to another?

Fuller: The progression of it starts with this one triggering event, the road rage incident. It was important to have a nice sequential build of the people’s actions. Even though each next domino to fall in the story was very important, I think it was important to have a very methodical build-up with the steam building up that leads to the big ultimate showdown at the end . . . . You’re unveiling the pieces of the onion for each character, and you want to do it in a way that builds. One event leads to this event, which leads to this event.

Zempel: For me, the key was keeping the parallels between Amy and Danny and what they’re going through and building off of them, and finding ways to keep their struggles connected to each other. They share very few scenes together.

CineMontage: What’s the trick to telling two independent stories that are nonetheless linked?

Zempel: On episode eight, when we get their backstories, that’s when we really understand the two characters. I’m really partial to that episode because I think it gives so much depth, especially with Danny and his relationship with Paul, and the conversation with Amy and her mother . . . . Their storylines are really separate—it starts with Danny, and then it goes to Amy—and seeing the ways that [the characters] were raised I felt really helped carry us to the finale when they confide in each other so much.

Fuller: One of the biggest challenges is keeping it nice and balanced where you’re rooting for the character at certain points, but then at some points you’re shaking your head: “Man, you are a mess.” . . . We had to make sure that everything was resonating where you didn’t tip too far into, “Oh, I love this character,” or tip too far the other way: “I hate this character.”

‘Terrifying as karaoke was, I think it really bonded us.’

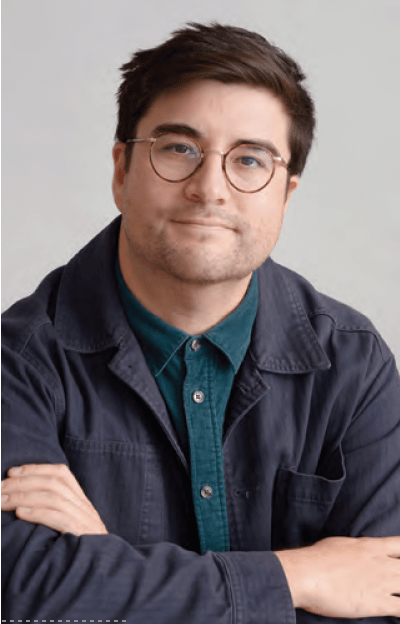

CineMontage: Jordan, why did you want to be part of the show?

Jordan Kim: “Beef ” is the kind of project that I’ve really been waiting for, especially as a half-Korean person working in the industry. One of the last shows that I’ve been on more frequently is “Awkwafina is Nora From Queens,” which I’m an editor, director, and producer on. That was one of the first shows that I worked on with a lot of representation in front of and behind the camera with Asian Americans . . . . When I heard about “Beef,” it was another level of specificity. “Beef” takes place in California and has a lot of stuff in [Orange County] and Koreatown, where I spent a lot of time when I was growing up.

CineMontage: Harry, can you talk about the performances?

Yoon: It is so wonderful to see an ensemble Asian American cast and to have so many of them willing to be idiosyncratic, to not be noble, to be very specifically, with warts and all, who their characters were.

Kim: One of the things that was great on our director’s cuts was letting things breathe a little bit more than you have time for in straight-up comedy. In my director’s cut of [episode] eight with Jake [Schreier, one of three directors on the show], I remember we added three minutes back in of people thinking about and registering what had been said in some of these more intense conversations, like George talking about divorce with Amy. It’s a pretty long scene and it’s really emotionally intense. The acting was so incredible that it was riveting to even just watch the dailies and see that the actors are bringing everything they have to these scenes.

Aside from the content and the representation, the pacing of [“Beef”] does not feel like a half-hour show to me. It feels like an hour-long . . . . You get to sit in these scenes and really give it the love that it needs to be with those characters in these emotionally intense moments.

CineMontage: Did each editor work independently? There are several episodes with shared credits.

Fuller: The shared credits came mostly from necessity of schedule, where Jordan had to move onto another project, as did Laura. It was basically just like “next man up” and a team effort. I was fortunate enough to be able to stay on throughout the entire process . . . . There were some interesting debates. Sometimes one person would feel a certain way about a situation and the other person would feel not exactly the same. It was really nice to have those kinds of debates about what the motivation was and what the scene was about. Just to have the discussion we hope the audience members will have.

Zempel: We all touched a lot of each other’s episodes. It was very collaborative. We started doing dailies from home, and then our post team would do a 45-minute Zoom check-in on Friday, to see how everyone was doing as a way to build morale. We coordinated a dinner that Harry planned for us where we all met up for Korean barbeque and did karaoke afterward. It was great because working from home you don’t get that camaraderie. Terrifying as it was to meet my co-workers for the first time and doing karaoke, I think it really bonded us.

CineMontage: What do you hope people take away from “Beef”?

Zempel: Amy and Danny meet in this one little moment in each of their lives, and then the show explores the full picture of these two people. The fascinating thing about the show is realizing that everybody is going through something. You never know what kind of day someone is having, how they were brought up, what they are dealing with.