by Edward Landler

Nashville (no relation to the recent ABC TV series) opened in New York City on June 11, 1975.

After 40 years, Robert Altman’s satiric tapestry of American society looks more accurate than ever. Holding up the capital of Country and Western music as a prism, the movie observes the fusion of business, politics, entertainment and the media that has become the norm. In its vision of a culture fixated on celebrity, the individual’s sense of self and place is as blurred as the lines between community and commerce.

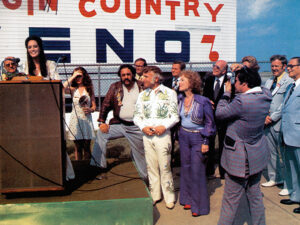

The film begins with a populist candidate’s presidential campaign van roaming the streets with loudspeakers blaring, “All of us are deeply involved in politics whether you know it or not — or like it or not.” The candidate is never seen, but he pervades the atmosphere as naturally as the Grand Ole Opry. The film catches the mingling of these two worlds over several days and nights leading to an outdoor concert sponsored by the candidate at the Nashville Parthenon.

Along the way, we view the intermittently interwoven lives of 24 distinct characters, each attached or drawn to the city’s music industry. Shot on location and in sequence, the movie constructs a recognizable terrain of dishonesties, resentments, compromises and humiliations rendered by and upon them all. It is also a musical with almost 30 songs performed on camera.

Altman said that he “learned the rules of the game from The Rules of the Game,” Jean Renoir’s 1939 perspective on French society just before World War II. It influenced the director’s films like A Wedding (1978) and Gosford Park (2001), but only Nashville comes close to Renoir’s scope and continuing timeliness.

Drawing from documentaries, neo-realism and improvisation, Altman created his own nuanced, multi-layered social environment. Paul Lohmann’s cinematography captured it with long shots setting characters in multiple planes of action, while the sound crew broke new ground in recording and mixing to bring the same rich texture to the movie’s music and dialogue.

The idea for the picture arose in 1973 after United Artists released Altman’s adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye. While the US Senate was voting to investigate the Watergate break-in, UA asked Altman to direct its script of The Great American Southern Amusement Company, a novel set in Nashville. He agreed to make a Nashville movie if they would finance Thieves Like Us (1974) — the Edward Anderson novel that Nicholas Ray filmed as They Live By Night in 1948.

On location in Jackson, Mississippi, Altman asked Thieves’ screenwriter Joan Tewkesbury to go to Nashville, scout the city and the music industry, and keep a diary of her experiences. He threw away UA’s script and, while filming Thieves, he and Tewkesbury began to devise an original story and characters using her notes to establish the Nashville setting. The filmmaker said he wanted to build on “very simple, basic stuff and put it into a panorama which reflected America and its politics.”

The political dimension grew as the Watergate hearings attracted more TV coverage and Altman asked Mississippi novelist Thomas Hal Phillips to create Replacement Party candidate, Hal Phillip Walker, for Nashville. Phillips wrote a 30-minute political platform which became Walker’s speeches, voiced by the writer over the loudspeakers in the movie.

After Thieves was done, Altman submitted Tewkesbury’s 140-page script and UA rejected it. Already unhappy with UA’s treatment of his last two pictures, the director took the project to producer Jerry Weintraub at ABC Pictures. With Weintraub’s backing, Nashville became what the director called “the first film I really had total control over.”

Thieves Like Us had given Louise Fletcher her first feature role after years away from acting. The actress’ relationship to her deaf parents intrigued the filmmaker. During that shoot, she and Altman together developed the character of Linnea Reese, a woman with deaf children, for Nashville. However, to avoid working again with Fletcher’s husband, Jerry Bick, a producer on Thieves and Long Goodbye, he offered the part of Linnea to Lily Tomlin.

This was Tomlin’s first movie and it brought her an Academy nomination for Best Supporting Actress. Meanwhile, the spurned Fletcher played Nurse Ratched in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), which won her the Best Actress Oscar. Tomlin had earlier turned down that role.

Before Nashville, the director made yet another movie, California Split (1974) with Elliot Gould and George Segal. In it, he experimented with the overlapping dialogue he would use extensively in Nashville. Altman’s use of the technique was sparked by Howard Hawks’ movies, but not being able to clearly separate two or more voices recorded on one track frustrated him.

Split’s production mixer Jim Webb, CAS, told CineMontage that engineer and producers assistant Jack Cashin told Altman that to get what he wanted, he should record multi-track. Webb had worked with radio mics at CBS and NBC and did multi-track sound for rock concerts and music documentaries; he suggested radio mics for the film’s multi-track set up.

Webb said, “We needed the multi-track system so we didn’t have to stage a shot for the microphone with booms and wires. With wireless mics, we could just lay down the separate tracks and watch the meters. All I needed to know was who Bob wanted to listen to.”

Webb and Cashin assembled the system, permitting them to restrict each track to a single input from each character’s voice. “We used eight tracks — seven for the actors and one to run sync with the camera,” said the mixer. Cashin built the portable 8-track sound console to run on batteries. The last part of the California Split shoot was the system’s dry run before starting Nashville. Webb also devised for the Nashville shoot a means to record telephone conversations on set in real time without the off-camera dialogue overlaps leaking into the on-camera dialogue.

With a $2 million budget, Altman wanted to shoot Nashville like a documentary with a small crew. From July through early September, 1974, Webb said, “We shot the movie at a dead run in eight weeks…we were flying.” During production, Richard Nixon resigned as US President.

To economize, Altman asked his actors and fledgling music supervisor, Richard Baskin, to provide original songs for the movie. The director didn’t “want to buy a lot of songs that were tried and tested when I was satirizing them.” He got what he wanted — a cross-section of country music, good and bad. Keith Carradine’s song, “I’m Easy,” won the Oscar for Best Song.

In town singing backup, Ronee Blakley heard Altman was buying songs and she sold him four of her compositions. When Susan Anspach wanted more money to play the Loretta Lynn-like character Barbara Jean, the director gave the part to Blakley. With a riveting “star” portrayal, the first-time actress was also nominated for the Supporting Actress Oscar.

To prepare the actors, assistant director — and soon-to-be writer/ director of Welcome to L.A. (1976) — Alan Rudolph boiled down the script to a running blueprint of characters’ stories and actions. With input from Tewkesbury, the director told his cast to write their own dialogue from scene to scene, “paraphrasing more than improvising.” During filming, however, he could change what they wrote on the spot.

Local people were brought in as audiences for the filmed musical performances. “We create an event and then we cover it as though it were actually happening,” explained Altman. The audiences, and sometimes the actors, did not know what would happen during a performance. Blakley and the director knew Barbara Jean would have a breakdown on the outdoor Opry Belle stage, but it came as a surprise to everyone else. Altman shot it four times with two cameras running and got the natural reactions he wanted.

Creating a tight production team was also crucial for the director. Working up from apprentice and assistant editor to editor for Altman, Dennis Hill told CineMontage that the filmmaker created the “same kind of camaraderie I experienced when I served in the military.”

Maysie Hoy, ACE, who co-edited Altman’s The Player (1992), was a production assistant and actor on Nashville. She recalled, “We built a community among the cast and crew. Everybody was on the call sheet in case we might need someone in a scene; Bob planted seeds in scenes for later. It was mandatory for everyone to go to dailies. We had a really good time.” Not everyone had a good time, though. Barbara Harris hated watching herself

on film and refused to attend dailies, earning the director’s disfavor.

Altman wanted Lou Lombardo to edit, as he had on the director’s last five films. They first worked together on industrials in Kansas City, but the editor was off directing his first feature. Webb recommended Sid Levin, ACE, with whom he worked on rock films. Having also edited Martin Ritt’s Sounder (1972) and Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973), Levin was hired. Lombardo’s son, assistant editor Tony Lombardo, ran the location editing room, syncing and projecting dailies. He coded the material and sent it to Levin and assistant editor Hill in Los Angeles.

All the music in the film was recorded live on set. Music supervisor Baskin (who also played a musician) picked the best musical take from each scene. Lombardo said, “We’d have to cut the picture to those music takes. We wound up syncing the whole picture to one music sound track.”

Using the multi-track system during the shoot, Webb and fellow production mixer Chris McLaughlin recorded all the audio separately and synchronously, virtually eliminating ADR. Webb said that sound editor Bill Sawyer put in only two bits of dialogue during post. Hill noted that re-recording mixer Richard Portman mixed down the sound to three tracks. His pre-dub of dialogue took two weeks, further bringing out its clarity and focus with the first use of the Dolby system to reduce noise levels.

Editor Levin said his main concern was “piecing together the dialogue in a continuous stream. With each actor mic’d separately, in a scene with four principal actors — each doing five takes and each take improvised — I had 20 choices to make.” After shooting, it took Levin 10 weeks to create the first assembly from several hundred thousand feet of film. Lombardo recalls, “Sid did a brilliant first cut…but he and Bob did not get along.”

Letting Levin go, Altman made Hill editor to cut the show to release length. “Dennis and I sat with Bob telling us what to do,” said Lombardo. Hill added, “He wanted the audience to work watching the movie, to really participate in the action.” Hill went on to edit four more films for the director. Lombardo later became an editor and cut five of Altman’s movies.

Paramount picked up Nashville for distribution and a three- hour early cut was screened in New York. Altman invited New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael to help deter the studio from re- cutting the picture. Triggering anticipation for the movie three months before its premiere, Kael wrote that it was “the funniest epic vision of America ever to reach the screen.”

The film was pared to 2 hours 40 minutes, “losing scenes that were more about texture and color than character,” noted Lombardo. Hill said Altman showed his attitude towards Paramount by opening the credits with a scratched up old sepia- tone Paramount logo. Nashville made a modest profit in its initial run and was nominated for the Best Picture Oscar, with Altman garnering a Best Director nomination.

Some writers criticized the film for making one of the country stars an assassin’s target at the end of the movie instead of the politician. Five years later, when John Lennon was murdered, a Washington Post reporter called Altman and asked him if he felt responsible for having inspired celebrity assassination. The filmmaker answered, “You shouldn’t blame me for the assassination. You might blame yourself for not listening to my warning.”

The movie had said it all. The dying star is carried off the Parthenon stage in front of a gigantic American flag and a bloody microphone is handed to Harris’ runaway farmwife who wants to be a star. Building up confidence and enthusiasm, she draws the stunned crowd into a bluesy hymn of denial, also written by Carradine: “You may say that I ain’t free, but it don’t worry me.”