by Peter Tonguette

In the early 1990s, when film editor Anne Goursaud, ACE, learned that Francis Ford Coppola was directing an adaptation of Bram Stoker’s 1897 horror novel Dracula, she thought it was a perfect pairing.

“My first thought was, ‘Oh God, this is perfect material for Francis — he’s going to do a fantastic job with this,’” remembers Goursaud, who, years earlier, had edited Coppola’s One from the Heart (1981) and The Outsiders (1983).

Yet the French-born editor had no inkling that she herself would be well-suited to the material. In fact, when the director contacted the editor about coming aboard the film — eventually titled Bram Stoker’s Dracula — she scoffed at first.

“I said, ‘Francis, why me? I’m French. I don’t know anything about vampires,’” she recalls. “He said, ‘OK, have you ever read that novel?’ I said, ‘Nope, sorry.’ He said, ‘Well, I’m sending you the novel and I’m going to send you the script.’”

As it turns out, the editor connected with the story and its undercurrents. “I read the book, and I thought, ‘This is genius — of course it’s for me,’” she explains. “Suddenly, the whole story came to life for me as how repressed Victorian female sexuality expresses itself through this passion and the metaphor of Dracula.”

The film, released by Columbia Pictures in November of 1992, assembled a sparkling assortment of stars to portray the famed characters of Stoker’s book, including Gary Oldman as the lead vampire, Count Dracula; Winona Ryder as Mina Murray; Keanu Reeves as Jonathan Harker; and Anthony Hopkins as Prof. Abraham Van Helsing.

Goursaud, who joined the film late in post-production, shared credit with fellow editors Glen Scantlebury, ACE, and Nicholas C. Smith, ACE.

The French Connection

Goursaud, though, grew up far from the glare of A-list Hollywood productions. The future editor was born and raised in the city of Tours, France.

“Most Americans have never heard of it, although it’s the third most-visited area of France for tourism,” says Goursaud, who grew up in a working-class family. “My father was an electrician and eventually had his own business as a contractor,” she says. “My mother put an emphasis on being a good student. From an early age, I wanted to go to Paris.”

The future editor received a degree in art history from the Sorbonne in Paris, although she admits to feeling like an outsider when she finally arrived in the City of Light. “Maybe that’s why I befriended so many foreigners,” Goursaud recalls. “Most of my friends were expatriates, and mostly Americans, and I got along with them — all sorts of Americans. Everybody said, ‘You’ve never been to New York? You have to go to New York.’”

Following an initial trip to New York, Goursaud relocated to the city for good to work on her thesis. Deciding that academia did not suit her, she accepted a job as an assistant to a fashion editor — “It was exactly like The Devil Wears Prada [2006] but my boss was super, super nice,” she says — before, at the suggestion of some friends, she began taking cinema classes at Columbia University.

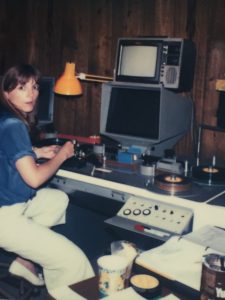

“I finally found what I wanted to do — something that went with my artistic desire, something that I realized I would be really good at,” recalls Goursaud, who harbored the goal of directing but felt she could earn a living in the cutting room in the meantime. “My instinct of survival told me, ‘Well, do that, and then once you’re very good at that, you can go back to directing,’” she says.

Among the editor’s earliest projects was a documentary about the cheerleaders of the Dallas Cowboys, A Great Bunch of Girls (1979). The film, co-directed by Mary Ann Braubach and Tracy Tynan, brought Goursaud to the attention of Coppola. “It was told to me that when he saw the documentary, he said, ‘She can cut,’” the editor states. “In a documentary like this, you had lots of montages and different variations. You had to really come up with editing solutions to tell the story, and so in a way, it made my editing shine.”

After hiring her to work on the bold, brilliant musical One from the Heart — which had been started by another editor — Coppola assigned Goursaud a sequence to cut, and after two weeks of toiling in isolation, she presented him with her results.

“He arrived, he looked at it and he said, ‘That’s what the whole movie should look like,’ and I was the editor,” Goursaud says.

On the final film, the editing credit is given to Goursaud, plus Randy Roberts, ACE, and Rudi Fehr, ACE, but for Coppola’s follow-up, the S.E. Hinton-based adolescent drama The Outsiders, Goursaud worked solo from the outset.

“This man changed my life,” she says of Coppola. “He went into a haystack, and he found this little thing in the haystack and pulled it out — and he said, ‘She’s a star.’”

By the time of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, however, the tables had turned: Goursaud had become an established, sought-after editor — her credits included Bruce Beresford’s Crimes of the Heart (1986), Hector Babenco’s Ironweed (1987) and Jack Nicholson’s The Two Jakes (1990) — while Coppola was struggling with creating his horror epic: The film had been cut, but a preview had not gone as well as expected.

“Everybody thought the movie was in big trouble,” Goursaud remembers.

Initially, Coppola turned to Goursaud to add interest to the love scenes. Yet, when the editor joined the production, she screened the complete cut and decided to tackle the montage of Dracula arriving in London. “It was a big, big montage with lots of elements: the boat, the wind, the garden, the maid, and then Dracula showing up,” recalls Goursaud, who worked alongside associate film editor Gus Carpenter on the Montage editing system. “Of course, Francis was gone again. When he came back, my montage was almost done, but not done — and I hadn’t touched at all the scene with the girls, of course.”

Coppola was at first perturbed that Goursaud had spent her time working on a scene they had not discussed, but once he had a look, he encouraged the editor to have a fresh look at the film as a whole. “The only scene that I did not rework in that movie was the crypt scene,” she remarks. “That I didn’t touch — it was perfect.”

Some scenes needed finessing; others required more intricate work. “Slowly, I worked my way through everything,” the editor explains. “Francis was very adamant: ‘You didn’t do this one yet; you didn’t do that one yet.’”

Yet, up to the evening before the film was mixed, producer Fred Fuchs was concerned that Bram Stoker’s Dracula lacked a proper opening. In a moment of inspiration, Goursaud had the idea to follow the film’s prologue set in 1462 — which more or less worked from the get-go — with Jonathan and Mina each writing diary entries: he on a train on his way to Dracula’s, she at home. “The movie never really got going and we didn’t know what to do,” she says. “Finally, we could go back and forth between him in the train and her, so that this dialogue of letters and narration back and forth was established. That absolutely made the movie work.”

The editor, who worked on the film from April through October of 1992, found the process of re-imagining a film to be thrilling. Instead of starting from scratch, Goursaud built on the work of the editors who came before her. “I discovered I love re-cutting something and making it work — really fun, fun, fun,” she says. “You’re not starting with a roll of clay. You have something that’s not quite built the right way, and you solve it. Maybe you need a couple images of this, a couple images of that.”

Goursaud viewed the experience of “solving” the puzzle of Bram Stoker’s Dracula as a fitting conclusion to her collaboration with Coppola.

“As I was making scenes work, I was thinking, ‘How cool is that that he put me on the map, and now I’m helping him make this magnificent movie work?’” she reflects. “I never said that to him, obviously, but that’s what I was thinking.”

In the end, Bram Stoker’s Dracula opened to solid receipts at the box office and largely respectful reviews; it received three Oscars out of four nominations: for Best Costume Design, Best Makeup and Best Sound Effects Editing for Tom C. McCarthy, MPSE, and David E. Stone. The film has acquired status as a cult classic in the 26 years since its release.

And, as it turns out, Goursaud was not done with the vampire genre: Three years after the release of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, the editor was hired to direct her first feature film, the direct-to-video horror film Embrace of the Vampire (1995), starring Alyssa Milano. “I thought, ‘This is so ironic — here I am doing a vampire movie,’” she laughs. “It was very, very successful. It cost nothing, was bought by New Line and made lots and lots of money.”

Today, Goursaud continues to make her own films, most recently directing, writing and editing a documentary about former United Artists executive Marcia Nasatir, A Classy Broad (2016) — but, if Coppola ever needs an editor to have a look at a project, she remains available.

“Francis,” she says, “is a special case.”