by Betsy A. McLane

Hollywood has always spent plenty of time and money trying to explain itself to its movie audiences. Behind-the-scenes “making of” movies are a time-tested staple of film and even television promotional campaigns. The best such films are historical records of the ardor and angst involved in getting a film on screen that also stand their own.

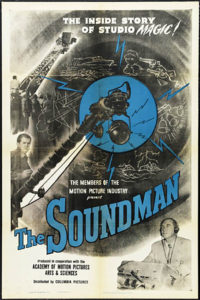

There are few documentaries that acknowledge professionals in the behind-the-scenes jobs, and virtually none about editors or sound personnel. Although one fascinating short film, The Soundman, was released in January 1950 as part of “The Movies and You,” a series of behind-the-scenes shorts co-produced by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) and funded by a group called the Association of Motion Picture Producers in partnership with various studios.

Grant Leenhouts was the series’ producer of record, but there are no individual credits on the prints. There were a dozen black-and-white shorts released, all made between 1949 and 1951, and they were meant to be screened theatrically in 35mm as part of the then-standard program of shorts, cartoons and features in cinemas.

Each title was produced at one of the major studios: Let’s Go to the Movies at RKO, This Theatre and You at Warner Bros., The Art Director at 20th Century-Fox, Movies Are Adventure at Universal-International, The Cinematographer and Screen Actors at MGM, etc. The Soundman was made at and distributed by Columbia Pictures. Of these, perhaps the best known is Let’s Go to the Movies, which was added to the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress in 2008.

Strangely, there is not a title devoted to picture editors, although one was originally planned. Sixteen scripts were written, but only 12 were completed. There were even plans for one color production, The Stylist. There were also plans to dub 35mm prints into other languages for foreign distribution, and it appears that at least a few of the films were released on 16mm for non-theatrical educational use. There is no extant explanation of why the series ended.

The Soundman was directed by Aaron Stell (1911-1996), a 40-year member of the Editors Guild who cut many important theatrical features, as well as TV movies and series. His editing credits include Touch of Evil (1953), To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), Love with the Proper Stranger (1963) and Silent Running (1972). Stell was awarded the ACE Career Achievement Award in 1996, shortly after his death.

Helmed by a post-production professional, The Soundman is a unique document of how sound departments worked in the later days of studio system dominance. The narrative is simple. It begins with (uncredited) actors Lola Albright and Jack Carson playing out a scene on a sound stage, surrounded by filmmaking equipment, with the microphone noticeably hovering above their heads. The actors, who married in 1952, were shooting The Good Humor Man(1950) at the time, and The Soundman shows a scene of that film being shot.

A friendly, male “Voice of God” narrator tells the audience, “Not so long ago, we had this…” A montage of silent clips follow, including comedy, drama and a scene from Hollywood’s biopic version of Thomas Edison’s life, Edison the Man (1940), in which Edison’s (Spencer Tracy) hand is seen turning the crank to replay his voice speaking his first sound on disc words, “Mary had a little lamb…” The Soundman returns to 1949, and, after a scientific-type shot of a sound wave on an oscilloscope, follows the steps that occur from the time that Albright’s and Carson’s words are captured and controlled by the recording engineer (Local 695 member George Cooper, playing himself) through each stage of sound post-production until a picture is screened in a theatre. Cooper was the patriarch of an IATSE film family; he was husband to Arlene (script supervisor, though pre-Local 871), father of Ron (production sound, Local 695) and grandfather of Chris Cooper (production sound, Local 695).

The film is detailed in its report of how many highly proficient specialists trained in the “science and acoustics of sound” are required, and it is justifiably lavish in its praise of the men who do the work. Of course, it being 1949, almost everyone in The Soundman except Albright is male, although an adorable woman is shown in a production still smiling as she files boxes of pre-recorded sounds in the library. The men are dressed in shirts and ties, and often sports jackets.

According to retired Guild sound editor James Nelson, who worked with George Cooper on Birdman of Alcatraz and Walk on the Wild Side (both 1962), The Soundman short represents the industry and the profession as it was in the 1930s and ‘40s. When Nelson began working in the mid-’50s, the tools and practices had already changed significantly, he said.

Bison Archives

The Soundman is, as the title card says, “Presented by the Members of the Motion Picture Industry,” meaning, in part, the members of AMPAS, which in 1950 numbered around 1,800. The Academy has long been dedicated to educating the public about all aspects of motion pictures, and its strong support of educational programs continues to this day, if largely unsung. AMPAS’ ongoing work in film preservation is also invaluable, and “The Movies and You” segments are currently in the process of being restored and preserved in its archive in Hollywood.

Also responsible for The Soundman (and thousands of other movies) being available today is Dick May, vice president in charge of preservation at Warner Bros. May, along with Roger Mayer, were responsible for saving the MGM library for decades when other studios were destroying what they considered to be worthless older films. Although The Soundman was not an MGM production, it has a place today in the Turner Classic Movies collection, thanks to Mayer and May.

It is a film that everyone in the industry should watch. Around 10 minutes in length, most of it can be seen here. It is valuable viewing not only as a curiosity, but also as a tribute to the artistry and dedication to perfection that characterize the profession of sound recording. To master any craft, one must be familiar with its history, even if that history seems out of touch with today’s world.