by Edward Landler

The people best fitted to make pictures for television will be those who combine a thorough knowledge of picture-making techniques with a real sense of entertainment values and the imagination to adapt their abilities to the new medium.

– Samuel Goldwyn, “Hollywood in the Television Age”

Legendary movie producer Sam Goldwyn wrote the quote, opposite, in an article for The New York Times Magazine in 1949, just as television was emerging as a major mass medium. During the previous year, the number of American cities served by the new medium rose from eight to 23, the number of stations jumped from 17 to 41 and the sale of TV sets multiplied five times over the number sold in 1947. It was estimated that between 1947 and 1949 the opportunities for viewing TV increased 4,000 percent.

Goldwyn sagely noted in his article, “Instead of any talk about how to lick television, motion picture people now need to discuss how to fit movies into the new world made possible by television.”

From the perspective of post-production personnel, Goldwyn’s perspective turned out to be prophetic. With the growth of television work, membership in the Editors Guild’s IATSE Locals 776 and 771 (merged now as Local 700) rose dramatically over the following 15 years. Over the same time, re-recording mixers, recordists, maintenance engineers and projectionists (all classifications in IATSE Local 695, which would transfer to the Editors Guild in 1998), as well as engineers and sound technicians also increased in ranks with the new medium’s growth. In addition, the dawn of television created the job of technical director.

The first direct fitting of movie post-production people into television programming came in 1947 with the first hour-long filmed TV show, Hopalong Cassidy, starring William Boyd as the silver-haired, black-clothed cowboy hero. But these hour-long actioners were not originally produced for TV. They were the popular, low-budget Westerns produced from 1935 on for theatrical distribution, cut down (by union editors) for one-hour TV slots with commercial breaks. Later, from 1952 to 1954, a half-hour series version with Boyd was filmed especially for television.

But in 1952, more than 80 percent of all TV shows were broadcast live. Some film editors found work preparing filmed kinescopes of live shows for delayed broadcast to different time zones. News and public affairs programming, though, found a more crucial way to integrate film editors into their broadcasts.

In 1945, NBC’s first news show was produced by Paul Alley, who hired newsreel editor David Klein to splice together newsreels for TV to be narrated by Alley. This became the Camel Newsreel Theatre and then, in 1949, the Camel News Caravan with John Cameron Swayze plugging Camel Cigarettes live on camera in between the news films. In 1948, the staff of The CBS Evening News with Douglas Edwards, television’s first daily news show, included a film editor. The number of film editors on all three major network’s news shows increased steadily until film was superseded by videotape in the late 1960s.

In those early days of news broadcasting, news film shot overseas was shipped to New York on a DC-6 fitted with bolted-down editing equipment so that the footage could be cut en route and broadcast immediately upon arrival. When Queen Elizabeth II was crowned in 1953, the three major networks raced for the prestige of airing the coronation footage first. ABC won the race when it made a deal to pick up the Canadian Broadcasting Company telecast of the event. ABC’s film reached Canada before NBC’s footage arrived in Boston to be broadcast by NBC’s affiliate there.

BUTTON PUSHING

Fresh out of USC’s film school, future film editor William Cartwright found work in the early days of Los Angeles TV at the CBS affiliate station KTSL, which became KNXT in 1951. He told CineMontage about his work as an engineer, which was actually early technical director work (he called it “the operator of buttons”), on live shows, including Sunday morning religious programs and an evening talk show called Bachelor’s Haven. Editing consisted of switching the live camera to the television opaque projector — the “tel op” — which superimposed advertising cards over the camera image. He also switched to the “film chain” to integrate film material into the show.

Cartwright worked at both KNXT and the Times Mirror station, KTTV, during the early 1950s when the IATSE organized the local stations and he became a member of Local 776. At KTTV, he edited for Confidential File, a half-hour exposé-style public affairs show created by newsman Paul Coates and future film director Irvin Kershner. For the first half of the show, Cartwright cut down MOS footage of subject matter like gambling houses, B-girls, religious quacks and unscrupulous businessmen. The edited footage was broadcast with narration and was followed in the second half of the show by live studio interviews on the subject at hand.

In the early 1960s, Cartwright won Emmy Awards for his editing of David L. Wolper’s The Making of the President 1960 and The Making of the President 1964 — television documentaries that helped to introduce a new style of filmmaking, which in turn influenced fiction filmmaking. Adapting his cutting to the sense of immediacy evoked by handheld camera work, Cartwright’s editing gave the audience the sense of “capturing the verisimilitude of a scene instead of viewing it as a theatrical arrangement.”

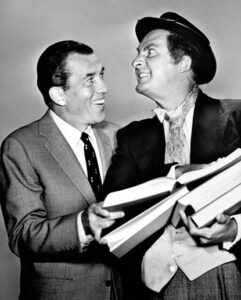

But, as Cartwright’s earliest experiences suggest, the overwhelmingly live TV programming of the late 1940s and early ‘50s brought the figures of the engineer and the technical director to prominence in the medium. With the debuts of Milton Berle’s Texaco Star Theatre and Ed Sullivan’s Toast of the Town variety shows, American audiences were drawn away from movie theatres to experience the intimacy of live performances in their homes.

The attraction of TV was further enhanced by the immediacy of the comedy of Sid Caesar’s Your Show of Shows and the intensity of the drama of live anthology shows like Kraft Television Theatre, Studio One, the US Steel Hour, Hallmark Hall of Fame and Playhouse 90. The live dramas — adapting classics and new theatre, along with original teleplays by writers like Paddy Chayefsky and Reginald Rose and featuring New York-based stage actors — are often cited as the reason for dubbing the early ‘50s as the Golden Age of Television. But there were also live episodic genre series: detective shows like Martin Kane, sci-fi series like Space Patrol and soap operas (called such because so many were sponsored by Proctor & Gamble) like Love of Life.

For all live drama on TV, though, production on a single stage in a fixed time encouraged the presentation of stories with tight structures and limited sets and scenes. This demanded a vastly different approach from the multi-scene story structure of movie storytelling. The technical director, as the live equivalent to the editor of film, had to develop his methods and skills through experience and trial-and- error — particularly the techniques of switching views on multi-camera live shoots at the command of the dramatic director.

Unlike filming movies, shooting in television studios with bulky TV cameras demanded a dependence on interior settings. Also, the size of TV screens and the need for strong lighting for video to capture the image promoted the use of close shots and close-ups. The earliest feature films of directors like Sidney Lumet, John Frankenheimer or Franklin Schaffner — who started in live television — reflect this tendency to shoot in close-up.

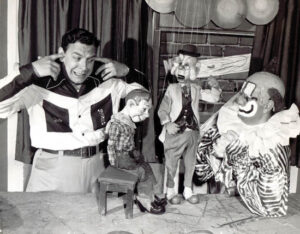

In 2008, the Archive of American Television videotaped a series of interviews with veteran technical director Heino Ripp, who passed away in 2009. In the late ’40s, the multiple-Emmy winner Ripp worked as an engineer with the NBC Development Group to create the modern television system. Over more than 40 years in television, he served as technical director for everything from The Howdy Doody Show (the first nationally televised children’s show in 1947), Your Show of Shows and the Kraft Television Theatre to numerous live specials and even Saturday Night Live.

In the archive interviews, Ripp described the role of the technical director in the early days. Not only were the early TDs responsible for pushing the switching buttons; they also prepared the video cameras and planned out with the director each camera’s movements throughout the show. No matter what the format or genre, Ripp noted, the cameras basically moved from three positions.

THE DEATH OF LIVE

By the late ’50s, two general trends in commercial television became apparent. First, more network programming was taking the place of local material on affiliate stations, and second, film programming and, during the 1960s, videotaped programming largely replaced live production on both the networks and the local stations. By 1961, less than 30 percent of TV shows were broadcast live.

A major reason for the decline in local station production was the sale of pre-1948 features to TV for broadcast. In 1955, the dying RKO Pictures was the first studio to offers its catalogue of 740 movies, followed in 1956 by Warner Bros., 20th Century-Fox and Paramount. Screen Gems, Columbia’s TV production division, distributed both the Columbia and the Universal libraries. Thus, the “movie generation” got its first education in cinema watching local movie shows like Million Dollar Movie — with the films edited down and segmented for commercials and time slots by editors.

Meanwhile, stories on film found new ways to fit themselves into what Goldwyn called “the new world made possible by television.” By 1949, episodic series filmed for television were introduced. Producer Frederick W. Ziv took the lead with shows such as The Cisco Kid and Highway Patrol that were syndicated for broadcast on local stations.

The first filmed situation comedy, Jackson and Jill, also hit the air in 1949. To streamline production to keep up with a weekly schedule, the producers of Jackson and Jill shot each show with three film cameras running simultaneously. Originally devised for NBC by producer Jerry Fairbanks, the multi-camera film set up was appropriated by Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz when they launched I Love Lucy for CBS in 1951. But they added a major precedent-setting innovation — they filmed the show in front of a live audience to heighten the comedy with laughter. The show’s editors, Dann Cahn, A.C.E., and Bud Molin, cut on a three-headed Moviola that could play all three camera angles at the same time. By 1957, the success of I Love Lucy allowed Desilu Productions to buy the RKO Studio, where it produced a wealth of episodic series for both networks and syndication.

During the 1950s, Lynn McCallon worked in editorial for The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show, as well as for syndicated Desilu series like Whirly Birds and The Adventures of Jim Bowie. He recalled for CineMontage a “leapfrogging” editing procedure devised for Burns and Allen to keep up with TV’s weekly schedule — two editors would work on a half-hour series, with each given two weeks to cut alternating episodes.

By 1957, the filmed episodic series dominated the airwaves. More than 100 filmed series were on the air, with the major studios producing their own series. Columbia set up its TV subsidiary Screen Gems in 1951, producing such shows as Captain Midnight and The Adventures of Rin Tin Tin. Warner Bros. followed suit in 1955 with Westerns and detective shows and, by 1958, provided ABC with 10 hours of programming every week.

Many film editors who had worked on studio features for years now found new careers in TV. For example, editor Art Seid had worked his way up the ladder at Columbia, from cutting Three Stooges comedies and other shorts to major features (including soon- to-be blacklisted writer-director Abraham Polonsky’s Force of Evil with John Garfield). With the rise of the filmed series, he moved over to television — where he amassed a mountain of credits, including The Amos ‘n’ Andy Show, Perry Mason, I Spy, The Mod Squad and a host of TV movies.

SOUND INFLUENCE

Another area of innovation in TV that significantly influenced the movie industry was sound editing. In 1953, engineers at Bing Crosby Enterprises developed 35mm magnetic stripe for recording sound on film in place of optical track. This breakthrough allowed far more accuracy in spotting sound for editing than previously possible, and also helped paved the way for multi-track sound recording on magnetic tape.

By coincidence, James Nelson was working at the same time as an apprentice editor on Rebound, a filmed anthology series produced by Crosby. Nelson moved on to sound editing and, in 1958, partnered with music executive Irving Friedman in the Primrose Company to provide music and sound effects editing services for television. Primrose became the leading sound effects company in the industry with the skills of sound editors like Milton Burrow, Fred Brown, Kay Rose, Bill Phillips and others, and provided its services to all of Screen Gems’ TV series, including Father Knows Best, Naked City, Dennis the Menace and The Donna Reed Show.

Nelson was credited as supervising sound editor on all these shows, and at one time worked on as many as six series in a single week. He put together the largest independently owned sound effects library in the field. In fact, it would be no exaggeration to state that Nelson originated the concept of sound design.

“The transfer process of individual sound effects was all developed for TV shows,” Nelson told CineMontage. “This was before stereo. Our editors did the pre-dubs for as many as 50 to 60 sound effects reels for each show, layering them down to one track. They had all the separate tracks ready for the show, and I would go to the stage to supervise the process.”

Apart from influencing sound editing, megastar Crosby also played a large role in the future of video recording. Industry legend has it that he wanted to find an inexpensive way to record and watch live TV programs that aired when he wanted to play golf, but he must have seen the commercial possibilities of such a technology. For whatever reason, he was a major investor in Ampex and, in 1956, Ampex introduced the first practical videotape-recording format. The recorder — named the VRX-1000 and later renamed Mark IV — was the size of two washing machines. Roy Dolby (who would go on to develop the Dolby noise reduction process and the multi-source theatre sound system) was one of the Ampex engineers credited with its invention.

In 1960, Ampex received an Oscar for technical achievement to go along with the Emmy it had received in 1957. Then, in 1961, Ampex invented helical scanning, the technology used in all electronic recording today. In 1963, the company introduced Editec for electronic video editing. It gave broadcast TV editors frame-by-frame recording control, simplifying tape editing and enabling animation, and was the basis for all subsequent electronic editing systems. The rest, to say the very least, is history — for editing both television and movies.

Finally, it should be noted that Goldwyn made one specific prediction about movies on television in his 1949 article: “The production of full-length pictures designed especially for home television will not become a practical reality for at least five or 10 years more.” He was right again. The first made-for-TV movie was See How They Run, broadcast on NBC in 1964.