by Kevin Lewis

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s film legacy is its musicals. Perhaps because it was the most politically conservative of the major studios, MGM was more comfortable with melodramas and musicals than with social issues. Four of MGM’s official eight Best Picture Oscars were for musicals, and The Broadway Melody (1929), released 80 years ago in February 1929, was its first winner in the second year of the Academy Awards.

Apart from its distinction as the first original all-talking sound musical––both The Jazz Singer (1927) and The Singing Fool (1928) were part-talkies––The Broadway Melody is notable because it introduced Arthur Freed, the film’s composer, to MGM and because it marked the debut of lip-synching to the playback of pre-recorded music. After Freed became a producer with The Wizard of Oz (1939), he organized the Freed Unit, which was responsible for the glorious reign of the MGM musicals, including the Judy Garland, Mickey Rooney, Fred Astaire vehicles, An American in Paris (1951), Singin’ in the Rain (1952)––the satire of early talkies, which featured the Freed-Nacio Herb Brown songbook––and Gigi (1958).

The film itself was a family affair. Irving Thalberg produced it with his brother-in-law, Lawrence Weingarten. But the film’s craftsman with the most lasting impact on the industry was another brother-in-law of Thalberg––Douglas Shearer–– who was the brother of the Queen of MGM, legendary star Norma Shearer. The Canadian-born Shearer was hired for the camera department in the late 1920s. On virtually his first assignment in the transitional era of sound recording of synchronized music and sound effects for silent films, he excelled as a sound engineer on White Shadows in the South Seas (1928) and was appointed head of the sound department. The picture editor was Sam Zimbalist, who became one of the studio’s major producers, culminating his career with Ben Hur (1959), the last best picture Oscar that MGM won.

In late 1928, Shearer was assigned to The Broadway Melody, which was conceived as the studio’s first all-talking musical picture with original songs––by Freed and Brown––including the immortal “You Were Meant for Me” and the title song. Thalberg’s impetus was that year’s The Singing Fool, the part-talkie with Al Jolson singing original songs written for the movie, which grossed a record-break- ing $5 million.

Shearer, who became one of the most honored figures in the history of the industry, revolutionized post-production on the film by introducing filming to play- back. Thalberg was a notorious perfectionist, often sending a movie back for extensive re-takes after sneak previews. He ordered the re-shooting of a production number, “The Wedding of the Paper Doll,” which was shot in very expensive two-strip Technicolor. Thalberg wanted more dynamic staging but the cost for re- shooting was prohibitive. The orchestra would have to be re-hired also. Sound stages were at a premium and were booked way in advance.

What seems elementary now was revolutionary then. According to The Lion’s Share (the official MGM history penned by Bosley Crowther in 1957), Shearer felt that the original recording was perfect––so why should he record it again? Just play back the recording through loudspeakers while the action is being photographed silent, and have the singer/dancers mime to the music, he figured. Whether Shearer conceived of this solution because he thought like a sound engineer, or was frustrated by his micromanaging brother- in-law––or it just made financial sense––is lost to history. The process became standard practice immediately and continues to this day. According to sound editor Louis Bertini, MPSE, “The concept of play- back is much the same now as it was then. Today, instead of a tape or disc being played, ProTools is brought onto the set for the playback.”

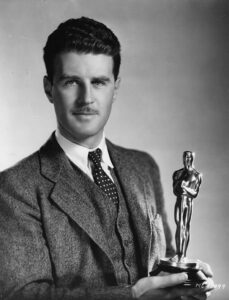

In a career that spanned from roughly 1927 to 1968, Shearer was nominated 21 times for Academy Awards for Sound Recording and Special Effects, winning five Oscars for the former, two for the latter and four honorary Scientific and Technical Awards. The 1937 honorary Oscar was for “a method of varying the scanning width of variable density sound tracks [squeeze tracks] for the purpose of obtaining an increased amount of noise reduction,” a significant technological advance and time-saver for sound editors and mixers.

Photo courtesy of Marc Wanamaker/Bison Archives.

How was sound recorded at the dawn of the talkies era? The two main methods were sound-on-film and sound-on-disc, and both systems may have been used during production of Broadway. Fox Movietone pioneered optical sound, which was recorded on a separate reel of celluloid 35mm film from the silent picture. Both were then combined into a composite print for theatrical distribution. Movietone composite prints had a cropped image to accommodate the optical track. That became the standard technology after 1929.

Warner Bros. developed Vitaphone, a sound-on-disc method, which incorporated a 16-inch shellac phonograph record on a turntable interlocked with the full- aperture silent film projector in perfect match-up. This was the system used by a majority of hastily sound-equipped film theatres in 1928 because it did not require the purchase of sound projectors. Sound-on-disc was abandoned after 1930 because if the record (which had a capacity of only 20 plays) skipped, it was out of sync with the picture from then on. Also, if the film broke and had to be spliced, the sound did not match. However, Vitaphone dynamic range as well as less static and surface noise than early optical film tracks.

Whether Shearer used the sound-on-film or sound-on-disc method to originally record the film is not known. Ron Hutchinson, founder of the Vitaphone Project––a group of film and record collectors dedicated to locating and restoring Vitaphone soundtrack discs––told Editors Guild Magazine, “In early 1928, all the studios decided to use Movietone because it was an easier, more mobile system. The Vitaphone discs could not be edited, like optical film could, but immediate playback on the set for re-takes was possible with the discs because the optical film would have to be processed in a lab. It is very possible that The Broadway Melody was shot on a wide-width optical track and also on sound-on-disc.” The film was exhibited in three versions: a Movietone print, a Vitaphone print and the silent ver- sion, which was only a little more than half of the movie, to accommodate theatres equipped with either sound technology––or none.

The Broadway Melody is a rather simple backstage story of a vaudeville sister act that is separated by their mutual love for a hoofer. The three leads were silent stars Bessie Love and Anita Page and Broadway star Charles King. Love went to England, where she was cast in small roles in major films until her death in 1986. Amazingly, Page continued making films into her 90s, one of which–– Frankenstein Rising––was forthcoming when she died at 98 this past September. King died of pneumonia during a USO tour in 1944.

The succeeding three official editions of the film––Broadway Melody of 1936, Broadway Melody of 1938 and Broadway Melody of 1940––were variety revues which showcased, among many musical performers, the dancing brilliance of Eleanor Powell and Buddy Ebsen.

After Thalberg died in 1936, Louis B. Mayer, like Louis XIV at Versailles, made sure that the court of MGM––producers, directors, writers and stars––revolved around him and his iron rule. He relied almost solely upon Shearer and his supervising film editor, Margaret Booth. Mayer was fired in 1951 by Loew’s Inc. and Booth and Shearer both left MGM in 1968, by which time virtually all of the creative talent that made the studio great had vanished or died.